The English Conquest and the Origins of Religious and Political Divides

The background to the modern Irish Question, the Northern Ireland “Troubles” of 1968-94 and the ongoing peace process lie deep in Irish history. While British involvement in Ireland dates back to the 12th century and the partial conquest of the country by the Anglo-Normans, it was the Ulster Plantation after 1600 which set the geo-political and religio-political molds of modern Ireland and Northern Ireland. Irish Catholic resistance to English conquest, particularly in the northern province of Ulster, led directly to the military defeat of the Gaelic Irish, the confiscation of their lands and the establishment of a colony of English and, particularly, Scottish Protestant settlers in the north of Ireland from 1610 onwards.

The victory of the Protestant King William III over King James II and his Irish Catholic allies at the Battle of the Boyne in 1690 resulted in the Protestant minority ruling Ireland under the Crown and the confirmation of the plantation land settlement. The penal laws, passed by the “Protestant Ascendancy” parliament in Dublin after 1691, excluded Catholics from political and economic power, a situation which continued effectively until the emancipation of Catholics in 1829.

The successful industrialization of Belfast after 1850 brought prosperity and reinforced the strong pro-British outlook among the masses of Ulster Protestants. For them, Home Rule (the demand of most Irish Nationalists for a devolved parliament in Dublin with control of local affairs) meant subjection to the domination of a Catholic government and legislature which would deprive them of their civil liberties: “Home Rule means Rome Rule,” they declared.

Home Rule or Union with Britain?

The period between 1880 and 1914 witnessed the struggle between Irish nationalists (including northern Catholics) and Ulster Unionists (supported by powerful British Conservative allies) over the question of national self-determination: The Catholic/Nationalist majority favored a Home Rule parliament for the whole island. Ulster Protestants/Unionists (a local majority in the north), however, insisted on the status quo: direct rule from Westminster and the safeguard of being part of a large Protestant majority in the United Kingdom. A Home Rule Act was finally passed at Westminster in 1914 with British Liberal support, but its passage provoked bitter opposition from northern Protestants, mobilized by Sir Edward Carson. The Ulstermen formed an illegal private army, the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), to resist — ironically — the will of the British parliament by force, if necessary.

Carson reacted by reigniting the flickering flame of Irish revolutionary nationalism and inspired the formation of the pro-Nationalist Irish Volunteers, set up in 1913 “to defend Ireland’s rights.” “The Manifesto of the Irish Volunteers” of November 25, 1913 stated: “The object [of] the Irish Volunteers is to secure the rights and liberties common to all the people of Ireland…”1 As the rival armies faced each other, compromise seemed impossible and by 1914 Ireland was on the brink of civil war.

This catastrophe was only averted by the outbreak of World War I, but the wartime suspension of Home Rule meant that the Irish crisis was merely postponed, not resolved. The situation was transformed by the Easter Rising of 1916, launched in Dublin by a militant Republican minority in support of an Irish Republic. The execution of the insurgent leaders generated an upsurge of support for an all-Ireland Republic (rejected by the British for strategic reasons) the establishment of Dáil Eireann in 1919 (set up by a majority of Irish representatives elected to the British Parliament in the 1918 election and constituting an independent Irish parliament), which declared an all-Ireland republic; and a War of Independence between the Irish Volunteers (renamed the Irish Republican Army) and British forces from 1919 to 1921.

The Division of Ireland

The British coalition government responded to these developments with the 1920 Government of Ireland Act dividing the island and establishing the sub-state of Northern Ireland in the six northeastern counties. The remaining 26 counties became independent of Britain according to the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921. The treaty had envisaged a Boundary Commission to redraw the border between North and South but, in the end, the 1920 partition became permanent.

Within Northern Ireland, the new self-governing entity in the United Kingdom, Nationalists formed one-third of the population, amounting to about 450,000 people. The Nationalists rejected partition as symbolizing the “mutilation of the Irish nation” and quickly adopted a “non-recognition” policy towards the new state and its parliament. More immediately, they looked to Sinn Féin (the IRA’s political wing) and its leaders, Eamon de Valera and Michael Collins, to secure a united Ireland in Anglo-Irish negotiations. The Irish Civil War (1922-23) and the death of Collins, their chief interlocutor with London, left northern nationalists demoralized and leaderless as peace slowly returned to a divided Ireland. Both for Unionists and Nationalists, Stormont, the new seat of government opened in 1932, became the symbol of “a Protestant Parliament for a Protestant state” in Craig’s telling phrase. There was no sign of a rapprochement between the two communities or between North and South, while the Catholic minority were subjected to discrimination and gerrymandering. The British government failed to use its overriding powers to ensure fair play.

The post-World War II years and the return of a radical Labour government in Britain in 1945 saw a sweeping social and economic revolution in Northern Ireland as the new British welfare state was extended to the region, financed by the British tax-payer. The Stormont Education Act of 1947 put equality of opportunity within the grasp of all Irish children and included state-aided university places based solely on merit.

These advances did not, however, come about without friction and sectarian controversy surfaced both in educational reform and in the health service. In 1947 the Northern Ireland government refused to follow the example of the British government which had introduced “one man, one vote” for parliamentary and council elections. This blatantly political decision, which disenfranchised many working class voters (disproportionately Catholics) was designed to ensure Unionist control in Nationalist districts. It would motivate the civil rights campaign two decades later.

From the Civil Rights Movement to the Eruption of Political Violence

By the early 1960s, Nationalist politics in Ireland were being influenced by three factors: the more liberal policies of the new Unionist prime minister, Terence O’Neill (1963-69), the conciliatory Northern policy of the Republic’s new modernizing Taoiseach, Sean Lemass, and the mounting demand for change from the growing numbers of articulate middle-class Catholics, who had benefited from of the post-war “educational revolution.”

In this climate NICRA (Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association) was formed, a broad progressive but largely Catholic front which drew inspiration from the black civil rights movement in the United States. It held its first major civil rights march on October 5, 1968. In the general election of February 1969 the election of key civil rights leaders, including John Hume, reflected Catholic support for the new style of politics advancing civil rights for all Irish. Hume heavily criticized the Nationalists for failing to offer constructive opposition t to the Unionist regime. Thus the scene was set for the 1970 merger of various civil rights MPs into the left-of-centre Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) committed to political participation.

It was during that summer’s marching season that political violence became prominent in Irish politics. In August 1969 outright sectarian warfare erupted in Belfast and Derry in which six died. The British Cabinet sent troops to restore order. This changed the dynamic with Westminster gradually assuming responsibility for security in Northern Ireland.

Events moved rapidly between 1969 and 1972 when violence and intimidation forced 60,000 people to move home. As vigilantes manned barricades, the rise of the Provisional IRA and its subsequent bombing campaign transformed the situation, aligning the British Army with the Unionist government. As violence escalated in August 1971 the new Unionist prime minister, Brian Faulkner, introduced internment to defeat the IRA; it was a one-sided weapon which alienated almost the entire Nationalist population. The military’s shooting of 13 civil rights marchers in Derry on “Bloody Sunday” of January 30, 1972 completed the alienation of the minority and forced British Prime Minister Edward Heath to suspend the Belfast government and introduce direct rule from London. In Faulkner’s words, Unionists “felt betrayed,” while Nationalists rejected any return to Unionist one-party rule.2

From the Collapse of Power-Sharing and the Downing Street Declaration

Over the next two years, the British government pursued a strategy of power sharing and installed the North/South Council of Ireland in accordance with the Sunning Dale Agreement, in order to reflect the Irish identity of the minority. Established in January 1974, the power-sharing executive soon collapsed due to a loyalist strike and a reinvigorated IRA campaign. Among Unionists, power now shifted to a hard-line coalition which demanded Protestant majority rule and rejected any “Irish dimension.” There were fears of a British military and political withdrawal from Northern Ireland as economic decline was matched by a spate of sectarian atrocities in the mid-1970s.

The collapse of the Agreement was a watershed for the SDLP. It was in the so-called wilderness years between 1975 and 1985 that John Hume (SDLP leader and MEP from 1979) began his remorseless shuttle diplomacy between Dublin, London, Strasbourg and Washington. He succeeded in winning the ear of Dublin, the influential Friends of Ireland in the US Congress and the leaders of the European Community.

By the early 1980s, the SDLP was faced with the emotional trauma of the hunger strikes, in which 10 Republican prisoners had died, escalating violence and the refusal of Unionists to share power with Nationalists. Hume’s response was two-fold: Firstly, he successfully pressured the Dublin political establishment to set up the New Ireland Forum (1983-84) to outline a shared vision for a future united Ireland and to utterly reject the use of violence.

Hume’s supreme achievement perhaps was to persuade the British and Irish governments of the need for a new framework in which “the totality of relationships” could be addressed.3 This led to arduous British- Irish negotiations which resulted in the Anglo-Irish Agreement (AIA) of 1985, signed by Margaret Thatcher and Garret FitzGerald, which sought to transcend the “narrow ground” — the intractable divisions of Northern Ireland — and gave the Irish government a consultative role in the North for the first time. Through its machinery Dublin could put forward views and proposals on a whole range of issues including, critically, fair employment. The result was the Fair Employment Act (1989), which finally eradicated the sectarian discrimination in employment.

While the AIA outraged Unionists accused Thatcher of treachery, it paved the way for the painful process of reappraisal by both Unionism and the Republican leadership. The hunger strikes of 1980-81 marked the emergence of Sinn Féin as a serious political force. By 1982 they had collected 10 percent of the votes. Over the next decade Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness pushed Republicanism towards electoralism while pursuing a twin-track strategy of “the armalite and the ballot-box” — the simultaneous use of violence and political means in pursuit of their goal of a united Ireland. By 1986 they had recognized the legitimacy of the Dáil [the Irish parliament] for the first time, a prerequisite to their ultimate abandonment of violence.

By the late 1980s the Unionist parties, anxious to minimize Dublin’s entrenched role under the AIA, were inching towards talks with the SDLP and the Irish government in the hope of restoring devolution at Stormont. Like the British and Irish governments, they were, however, adamant that Sinn Féin should have no role in any negotiations even though they now represented 13 percent of the vote as they continued to justify the IRA campaign.

As early as 1972 the SDLP had sought to persuade the IRA to end their campaign. This was an objective Hume returned to in the Hume- Adams dialogue in 1988. For Unionism however, and for much of the Dublin media, the SDLP leader’s dialogue with “unrepentant terrorism” was unconscionable.4

The Hume-Adams dialogue centred on the key issues of selfdetermination, a British declaration of neutrality and conditions for a permanent end to the violence and led to the transformative Downing Street Declaration of December 1993. In that key document the British government of John Major declared it had “no selfish strategic or economic interest in Northern Ireland.” The government further wished to facilitate an “agreement among all the people of Ireland” and would work with the Irish government to achieve an agreement embracing “the totality of relationships.” [Joint Declaration by John Major and Albert Reynolds, Downing St., Dec. 15, 1993 (Her Majesty’s Stationary Office [HMSO] 1993]

Paths to the Good Friday Agreement

Over the next five years the active engagement of the two sovereign governments, successive Taoisigh and British prime ministers, U.S. President Bill Clinton, Irish and British officials, courageous individuals from both communities and Republican and Loyalist figures led to the paramilitary ceasefires of 1994. After many setbacks, notably the sudden breakdown of the IRA ceasefire in February 1996, these resulted in interparty talks chaired by Clinton’s peace envoy, Senator George Mitchell, and based on the Mitchell Principles of democracy and nonviolence. The final outcome was the Good Friday (Belfast) Agreement of April 10, 1998.

The Agreement was predicated on “balanced constitutional change” [P Bew and G Gillespie, Northern Ireland: A Chronology of the Troubles 1968-1999 (Dublin, 1999), p. 359] and the ability of the signatories to rise above the entrenched positions and mutual antagonism of the past. It addressed three strands of conflict resolution: power-sharing in Northern Ireland; North-South institutions to reassure Nationalists and East-West links to reassure Unionism. The Irish government agreed to amend its Constitution, replacing its extra-territorial claim long resented by Unionists by an aspiration to unity by consent while Britain agreed to repeal the 1920 Partition Act to assuage nationalist sentiment.

On the critical issue of paramilitary prisoners, the governments agreed to the early release of prisoners “on license” but without amnesty. In return, the IRA and loyalist paramilitaries agreed to use their influence to complete the decommissioning of all weapons within two years.

In regard to policing, a divisive issue since partition, it was agreed to establish an independent commission to create a police service representative of the whole Northern Irish community.

Finally, the Agreement was to be put to the people of Ireland, North and South, in simultaneous referendums in May 1998, as first proposed by Hume. The result was an overwhelming endorsement by 71% of voters in Northern Ireland and 94 percent in the Republic. For the first time ever, the entire population of the island of Ireland had voted to remove the gun from Irish politics and endorse a framework of democracy, equality and mutual cooperation.

Successes and Challenges since 1998

Since 1998 the peace process has faced many challenges. Initially, the reluctance of the IRA to decommission its arms posed an existential threat while the Agreement’s main signatories — David Trimble’s centrist Ulster Unionists and the moderate Nationalist SDLP — were soon displaced by Rev. Ian Paisley’s hard-line Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) and Sinn Féin. Yet, in 2007, following the internationally verified decommissioning by the IRA and further negotiations at St. Andrews in Scotland in 2006, these diametrically opposed parties agreed to work within the established institutions. Sinn Féin, for its part, signed up to policing and justice, reversing a century-old policy.

Since then Northern Ireland has enjoyed ten years of power sharing by former political enemies. This has resulted in the establishment of a new, inclusive police service and an end to the violence which had caused the deaths of 3,600 people — civilians, police, soldiers and paramilitaries — during the Troubles.

Yet, over the years, there have been recurring and often intractable challenges, following from the mistrust rooted in the violent legacy of the past, issues around culture and identity, disagreement about the nature of victimhood and the refusal of some paramilitaries to leave the stage. The British vote to leave the EU known as “Brexit” has created further uncertainty for both the peace process and the retention of the present “soft border” on the island of Ireland.

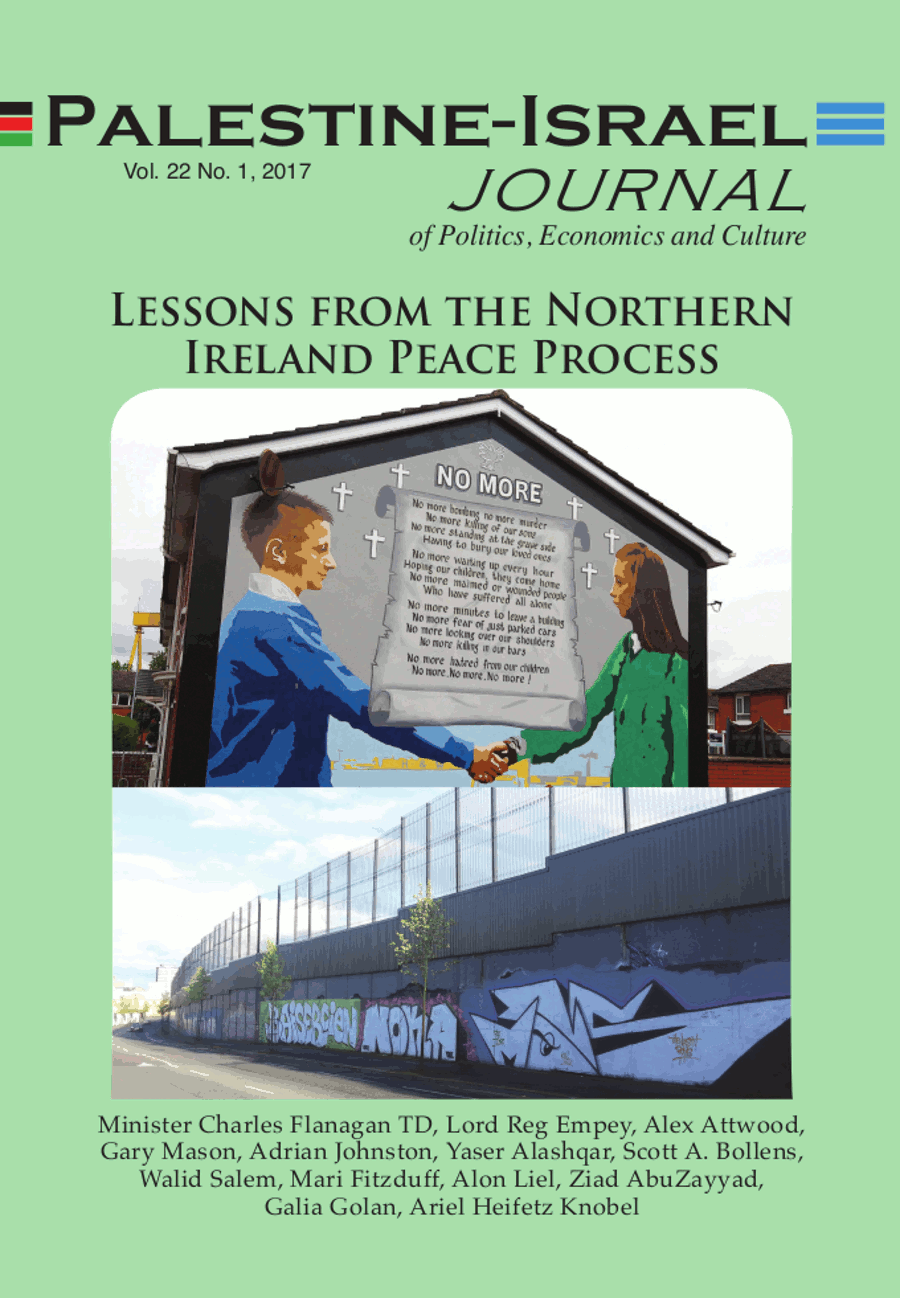

Paradoxically, despite two decades of relative peace and a more open, fair and vibrant society, Belfast today has more peace walls than it did in 1998. In particular, there is an urgent need for the Northern Ireland Assembly to tackle the underlying problems of sectarianism, segregated housing and education systems and to initiate meaningful steps towards a shared future. Cross-community bridges have been built, but much remains to be done by central government.

At the point of writing this article in the spring of 2017, the basic distrust between the two major government partners, the DUP and Sinn Féin, had brought about the collapse of the institutions. Notwithstanding the bitter recriminations, no one in Northern Ireland wishes to return to the nightmare of the past, and almost 20 years after the Good Friday Agreement, there is optimism that determined efforts to promote stability and reconciliation will prevail. This will require a return by all parties to the attitudes and compromises that inspired the 1998 Agreement. For what has been achieved through the Irish peace process is too precious — and too fragile — to be put at risk.

Endnotes

1FX Martin (ed.) The Irish Volunteers 1913-1915 (Dublin, 1963).

2Speech by Faulker on suspension of the Northern Ireland parliament on March 28, 1972 in Robert Kee, BBC Television History of Ireland, Programme 12, ‘Six Counties’ (BBC, 1979); ‘Towards a New Ireland’ (SDLP policy document, 1972).

3This phrase was used in the communique issued after the first Anglo-Irish summit meeting between the British prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, and the Taoiseach, Charles Haughey on Dec. 8, 1989. P Bew and G Gillespie, Northern Ireland: A Chronology of the Troubles 1968-1999 (Dublin, 1999), p 143.

4Ulster Unionist statement on Hume-Adams talks, Irish News, Jan. 12, 1988.

Sources

Marc Mulholland, Northern Ireland: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2002).

Patrick Buckland, The Factory of Grievances: Devolved Government in N Ireland 1921-39 (Gill and Macmillan, Dublin, 1979).

J Bowyer Bell, The Irish Troubles: A Generation of Violence 1967-1992 (Dublin, 1993).

Éamon Phoenix, Northern Nationalism: Nationalist Politics, Partition and the Catholic Minority in Northern Ireland 1890-1940 (Ulster Historical Foundation, Belfast, 1994).

Alan Parkinson and Éamon Phoenix (eds), Conflicts in the North of Ireland 1900-2000: Flashpoints and Fracture Zones (Four Courts Press, Dublin, 2011).

Ed Moloney, Paisley from Demagogue to Democrat? (Poolbeg Press, Dublin, 2008).

S Farren and D Haughey (eds), John Hume, Irish Peacemaker (Four Courts Press, Dublin, 2015).

Paul Bew and Gordon Gillespie, Northern Ireland: A Chronology of the Troubles 1968-1999 (Gill and Macmillan, Dublin, 1999).

Senator George J Mitchell, Making Peace (Heinemann, London, 1999).