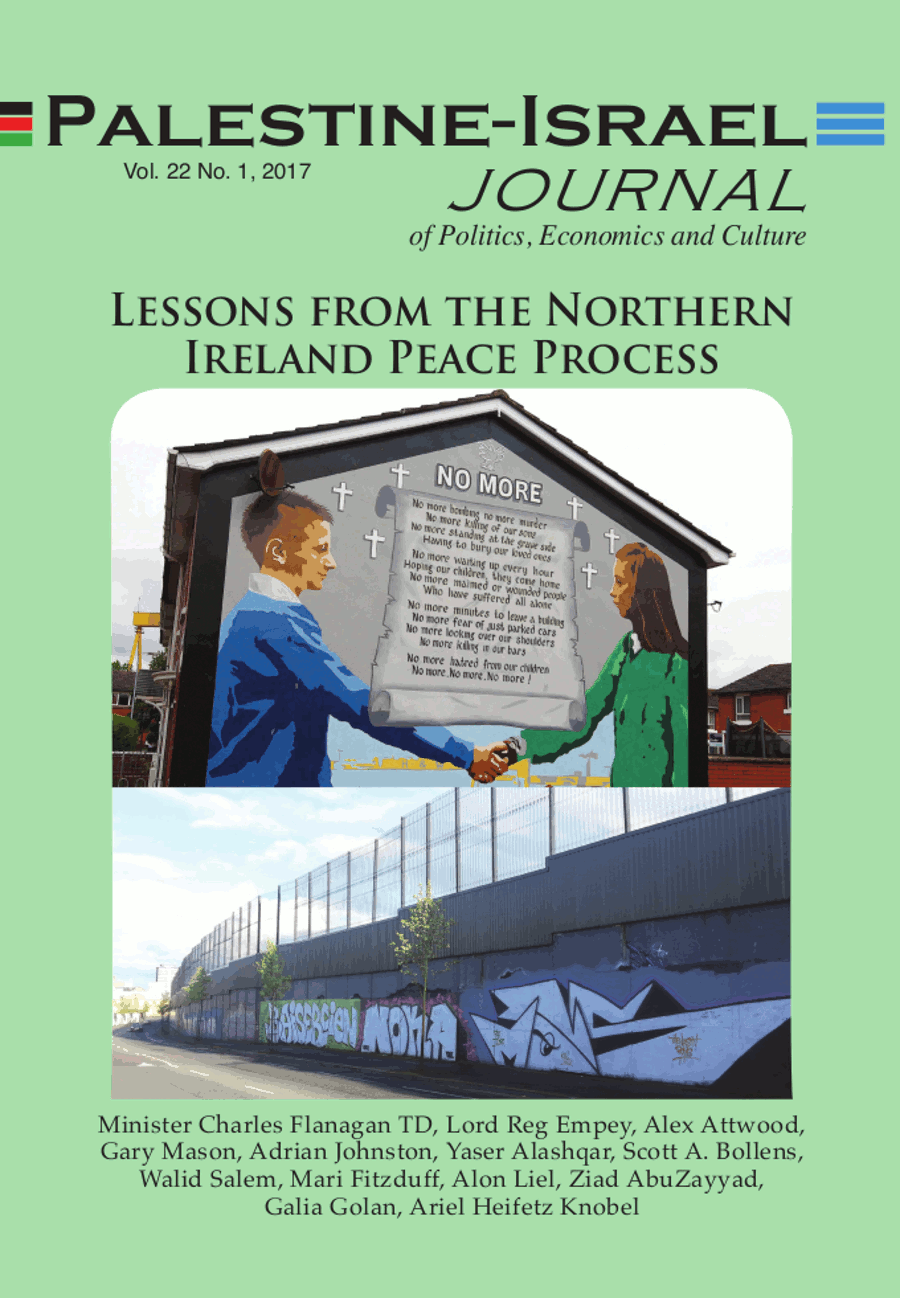

The road to the Good Friday Agreement, signed April 10, 1998, to bring an end to decades of sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland was not an easy one. To achieve the Agreement, potential spoilers were dealt with in a number of ways, including the involvement of the governments of Britain and Ireland, (patrons and past spoilers) in the talks. Negotiations were held with Sinn Fein even before actual decommissioning of the party’s military wing, albeit under threat of exclusion if violence recurred. There was third party mediation, conducted by the United States, home of a large, traditionally involved Irish diaspora. In addition, elections were held to choose ten parties to participate in a Northern Ireland Forum for the actual peace negotiations. Two cross community NGOs of Catholics and Protestants, such as the Northern Ireland Women’s Coalition, were among those elected.

Once negotiated, however, the supporters of the Good Friday Agreement faced one final hurdle before the Agreement could be implemented: public approval to be determined in a referendum.2 A referendum is considered a tricky mechanism; it is a tool usually opposed by political scientists mainly because of the ways in which the questions can be manipulated or an uninformed public deceived. Moreover, while a referendum theoretically gives the public a chance to have a say, it also provides a relatively safe vehicle, space, and opportunity for spoilers to mobilize their forces. The rejection of the 2014 UN Secretary General Kofi Anan plan for Cyprus, the victory of the “Brexit” vote in the UK to leave the EU and even more pertinent, the defeat of the Colombian peace agreement in the October 2016 referendum, were all evidence of risks of referenda. By contrast, the successful Yes campaign in Northern Ireland paved the way for the implementation of the Good Friday Agreement. As such it provides one more of the lessons we may learn from resolution of the conflict in Northern Ireland, specifically: how peace-makers might cope with would-be spoilers.

The “Yes” Campaign

Potential spoilers were, of course, the all-out opponents of the Agreement but also included many within the protagonists’ own parties or publics. Thus the Catholic John Hume, for example, leader of the more moderate Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), had to contend with many in his party who opposed working with their militant rivals, Sinn Féin. The Protestant leader of the Unionists, David Trimble, who helped negotiate the Agreement, had an even tougher task of contending with the steadfast opponent Ian Paisley, head of the Democratic Unionist Party and also the smaller UK Unionist Party. Beyond these was a major target: the doubters or skeptics consisting of many people with long held grievances and deep-seated fears – a fertile field of referendum voters in both communities susceptible to the arguments of the all-out opponents to the Agreement. Professional advice given to the Yes campaign was to concentrate on the latter group and to avoid defending or rebutting attacks on specific elements connected with the content of the Agreement, such as the power-sharing clauses or the monitoring mechanisms, as that would likely lead to confusion rather than persuasion. The campaign, therefore, related to the Agreement as a whole, its value or implications. It employed a variety of tactics designed to reach people on an emotional or personal level, both through activities and “helpers” in the framing and “selling” of the Agreement.

Activities included public appearances not only by the political leaders themselves – together – as in a dramatic Hume-Trimble handshake, but also by sports figures and popular entertainers such as the Irish rock group U2 who acted as “helpers.” Specific audiences were targeted. For example, Trimble himself went into prisons to speak with former Union fighters, and he met with militia and police groups. Both Catholic and Protestant supporters reached out to families of past victims not only to gain their support but also to involve them in the campaign when possible, as a counter to spoilers. This did not always work; on one occasion the celebrated release of former IRA prisoners, which was designed to win over skeptical Sinn Féin supporters, did little to allay Protestant fears and actually became what can be called “unintentional spoiling.” Media were also involved as “helpers,” as in the case of a joint editorial published by the right-of-center Unionist Newsletter and the nationalist Irish News in favor of the Agreement, reportedly having an effect in defusing some Unionist agitation.

Given the background of the leader of the “Yes” campaign, Quentin Oliver, who had been the director of the Northern Ireland Council for Voluntary Action, it was not surprising that a central part of the campaign was conducted by grass roots organizations. They organized meetings, joint rallies, and debates involving many of the cross-community peace and human-rights groups long active among students, workers, women, former victims and prisoners, clergy and others. Their activities often included track-two type encounters as well as meetings with politicians. Indeed, although theoretically independent, many of these activities were in fact coordinated with political parties, but nonetheless they were designed to – and indeed did – give people at every level a voice. Additional “helpers” – third parties from outside – were also engaged in the campaign, including a television appearance by then-U.S. President Bill Clinton. More importantly for the pro-Agreement Unionists’ campaign were the appearances not only by Prime Minister Tony Blair but also former Prime Minister John Major who countered spoiler claims by the UK Unionist Party that the Agreement would bring an end to the British identity of Northern Ireland.

The reference to British identity was suggestive of the importance of framing in “selling” the Agreement. However, here too the message was more general, personal and emotional. The overriding theme of the “Yes” campaign was a rejection of the past, the possibility of moving forward as clearly distinguished from what would be a return of the “Troubles” if there were not a decisive “Yes” vote. A “No” vote, as expressed by the U2 group, would play into the hands of “the extremists who’ve had their day. Their day is over…we are on the next century here.” This theme was fortified by frequent references to the changes that had taken place in the circumstances and especially in the adversaries including Sinn Fein. Either to prove their point, or to avoid raising expectations too high, Trimble and Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams both asserted that the other side was not monolithic. Speaking of change could and did rouse accusations of treason from the total spoilers in one’s own camp, countered by Adams, who claimed steadfast loyalty to the principles of his own side, and by Trimble, who said, “We are doing the right thing.” Indeed, these leaders – supporters of the Agreement – assured the doubters in their midst that they were giving up nothing but, rather, were gaining security that could be sustained, through peace.

The references to a possible return to the “Troubles” played on the public’s fears, portraying a “No” vote as one of hopelessness regarding the future – graphically employing traffic signs pointing forward or toward a dead-end to emphasize what was at stake.

A “Yes”3 vote was presented as patriotic, responding to the needs of all the people in Northern Ireland, but such references were also intended to create a sense of public ownership, that the Agreement not only served everyone’s interests but that it would be the people making history. Third party “helpers” such as Clinton and Blair also spoke of a “unique opportunity” and “no alternative” in what mediators often refer to as the “train leaving the station” technique – either you are on it or you get left behind. This fit the opposing arrows logo of the “Yes” campaign, but these third parties also hinted at cost/benefit elements, namely economic incentives.

The “Yes” campaign achieved a resounding victory in the May 1998 referendum: 71.12% “Yes,” including exit poll reports of over half of Unionists and 94-99% of Nationalists/Republicans voting in favor. Clearly some skeptical Catholics had been won over, but the real victory was the neutralization, even persuasion, of the expected spoilers from the ranks of the Protestants (Unionists/Loyalists). Although polls demonstrated positive effects after the Hume/Adams handshake, and opinion changes among youth following the U2 concert, it is difficult to draw a direct line between one particular aspect of the campaign or another. Leadership – including third party helpers’ – actions may have been critical, but the involvement of large numbers of grass roots activists, including former prisoners and victims as well as civil society groups, carried the carefully framed message to success. The fear of losing the relative security, that is, a return to the terrible time of the “Troubles,” gave way to a vote for a different, sustainable future through the peace agreement, as the Good Friday Agreement was presented.

Lessons Palestinians and Israelis Can Learn

Many lessons can be learned from the experience of the “Yes” campaign for dealing with expected spoilers of an Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement. In fact, both Israeli and Palestinian peace activists have and are already employing similar “helpers,” for example, in the two joint Israeli- Palestinian movements: the Bereaved Parents Circle and Combatants for Peace. In security-focused Israel past combatants carry some weight just as past imprisoned fighters in Palestine exude legitimacy, as do those on both sides who have lost loved ones in the violence of the conflict. Third party “helpers” – in our case involvement of the Arab states would not only provide backing for the Palestinians – especially important for the matter of Jerusalem, but also the regional acceptance sought by Israel. The advice adopted by the “Yes” campaign regarding framing is perhaps the most important point for future supporters of an Israeli-Palestinian peace agreement: rather than deal with the specific components – the content – of the agreement, it is best to speak of what the agreement offers as a whole. Repeated studies by leading Palestinian survey analysts Prof. Khalil Shikaki and Prof. Yaacov Shamir have clearly demonstrated that both publics remain uncompromising and far apart when presented with plans on specific issues, such as Jerusalem, refugees and borders. However, when presented with a whole agreement consisting of the same specifically rejected plans, the majority of both publics are in support. What is placed in the balance, like the opposing traffic signs of the “Yes” campaign, is a choice between two directions: a path to a dead end and return to the violence of the past, or a move forward toward the possibility of peace.

Endnotes

1A broader treatment of this topic can be found in the author’s contribution to a volume soon to be published, co-edited by Galia Golan and Gilead Sher, Spoiling and Coping with Spoilers in the Israeli-Arab Conflict. The term “spoilers” was introduced by Stephen Stedman, ‘Spoiler Problems in Peace Processes’, International Security, 22/2 (Autumn 1997), 5-57 distinguishing between different types of spoilers from “total spoilers” often using violence to “unintentional spoilers,” whose actions have an unintended negative effect, and various other types in between including skeptics as potential spoilers.

2A vote was to be held in the Republic of Ireland as well, to allow that country to sign.

3Quentin Oliver, Working for “YES”: The Story of the May 1998 Referendum in Northern Ireland, (Belfast: The “YES” Campaign, 1998), 60 (design by Saatchi and Saatchi; permission granted by the author).