There was a time when there were three major conflict issues on the international agenda: the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the South African Apartheid regime and the Irish conflict. Many observers felt that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict would be the first to be resolved, and that the other two were much more intractable.

But here we are in 2017: The Apartheid regime officially ended in 1994, after the success of the negotiations led by F.W. de Klerk and Nelson Mandela produced a new constitution and resulted in the election of a representative government with a non-white majority. Four years later, 1998 saw the signing of the Good Friday Agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the government of Ireland, ending over 40 years of violent inter-ethnic “Troubles” in Northern Ireland and creating a new inclusive Legislative Assembly (regional parliament) with both Nationalist and Unionist representation.

But here we are in 2017: The Apartheid regime officially ended in 1994, after the success of the negotiations led by F.W. de Klerk and Nelson Mandela produced a new constitution and resulted in the election of a representative government with a non-white majority. Four years later, 1998 saw the signing of the Good Friday Agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the government of Ireland, ending over 40 years of violent inter-ethnic “Troubles” in Northern Ireland and creating a new inclusive Legislative Assembly (regional parliament) with both Nationalist and Unionist representation.

In Israel and Palestine, as we approach the 50th anniversary of the occupation that began in 1967, both Israeli and Palestinian societies are characterized by a sense of great frustration and pessimism about the future. While public opinion polls indicate that a majority in both societies still supports a two-state solution and wants a peaceful, nonviolent resolution to the conflict, that majority also sees no strategy or path to realizing that outcome.

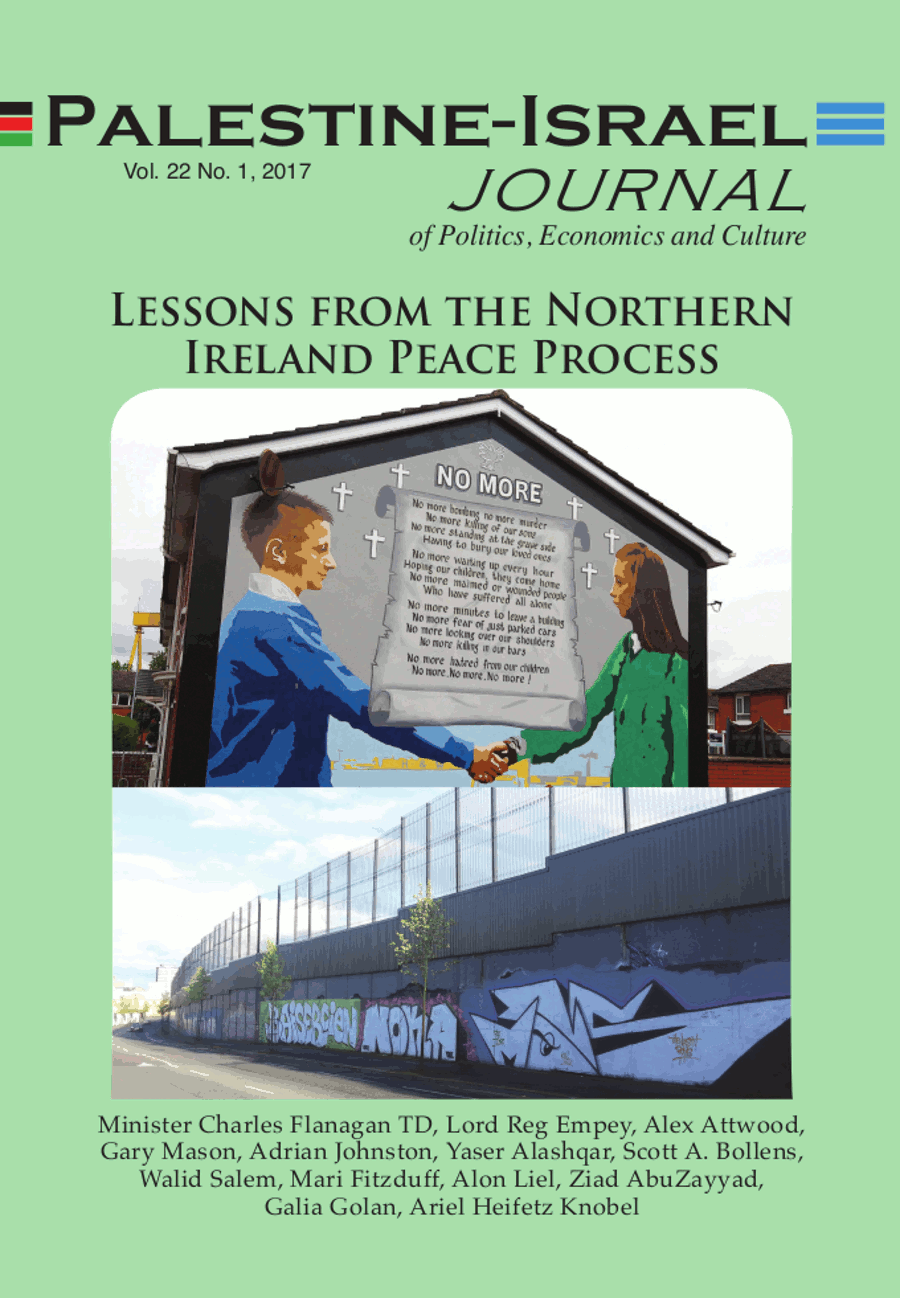

That led us at the Palestine-Israel Journal to decide to devote this issue, in partnership with the Irish Embassy in Tel Aviv and the Irish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, to an exploration of what possible lessons could be learned from the Irish peace process that might be applicable to the process of resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

I will admit that, before the intensive study tour of Dublin and Belfast that was organized for us by the Irish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, I found the nature of the problems in Northern Ireland quite confusing. I recently saw a film about an IRA attempt to buy arms in the United States, The Devil’s Own, made in 1997 by noted director Alan J. Pakula, and discovered that when the film was shown it was accompanied by a nine-page explanation of “The Troubles in Northern Ireland” so that viewers would understand the context! Because of the sensitivity of the topic, Princess Diana even got into trouble and was attacked by the British media for taking her two young children to see the film.

Thanks to the study tour, I have a much greater understanding of the issues, as well as clear conclusions about lessons that might be applicable to our situation:

1. A National, Not a Religious, Conflict

One of the reasons why it was possible to reach the Good Friday Agreement to end the violence was that both communities, the Nationalists/ Republicans and the Unionists/Loyalists, always viewed the conflict as one based on national identity, not religion. The Republicans aspire to one united Ireland, while the Unionists aspire to remain a part of the United Kingdom. It has never been a matter of Catholics vs. Protestants on a purely religious basis. That is what enabled the negotiators, backed by civil society and the international community, to arrive at the rational arrangements that were codified in the Good Friday Agreement.

That should be a lesson for us here not to allow our conflict to be transformed into a religious conflict between Muslims and Jews — which would be even harder, if not impossible, to resolve.

2. The International Community

The support of the Americans, led by then-President Bill Clinton, for the process and the role played by mediator/facilitator Senator George Mitchell were essential to advancing the process. An important role was also played by then-British Prime Minister Tony Blair, who sought a compromise to end the ongoing violence. He reached out to fellow social democrats with the SDLP (Social Democratic and Labour Party) who advocated nonviolence as the strategy for struggle and importantly also with Sinn Féin the main Republican party and the UUP as the then main Unionist party, to secure the 1998 Agreement.

It is clear that without the active, constructive engagement of the international community, it will be impossible to advance conflict resolution between Israelis and Palestinians.

3. International Funding and Civil Society

Three major funds helped to finance public and civil society support for conflict resolution in Northern Ireland. They are the International Fund for Ireland, EU Funds for Northern Ireland and an Irish Government Fund for Northern Ireland. The International Fund for Ireland was established in 1986 by the British and Irish governments to promote “economic and social advance and to encourage contact, dialogue and reconciliation between nationalists and unionists throughout Ireland.” The Fund has operated with the support from the U.S., Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the European Union. Since its establishment it has provided €849 million for over 5,700 civil society projects in Northern Ireland and Ireland.

Attempts have been made, particularly by the Washington-based ALLMEP (Alliance for Middle East Peace), to establish a similar International Fund for Israel and Palestine — so far without success. The primary international funding for conflict resolution in the Middle East comes from the EU Partnership for Peace Program (now called the EU Peacebuilding Initiatives), which provides annual funding of €5 million for civil society projects that support conflict resolution in Israel, Palestine and Jordan, and the USAID Conflict Management and Mitigation Program, which provides support of $9 million annually to Israeli and Palestinian conflict resolution projects. While these two international funding mechanisms, together with other European government aid agencies, have provided much-needed support for civil society activity in support of Israeli-Palestinian conflict resolution, their collective financial scope is far from the dimensions that have been provided by the three funds that focused on helping to building support for conflict resolution in Northern Ireland. The international community could, and should, provide more much-needed funding to help build public support for a peaceful, fair and nonviolent resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict based upon a viable two-state solution.

4. The Role of Women

The role of civil society organizations led by women from both sides of the divide played a major role in convincing both communities in Northern Ireland to end the violence and move towards a workable political compromise. When the violence associated with The Troubles grew in the 1960s and 1970s, this found expression in the Women for Peace movement co-founded by Mairead Maguire, Betty Williams and Ciaran McKeown (see the interview with Maguire in this issue). Maguire and Williams were awarded the 1976 Nobel Peace Prize for their work encouraging a peaceful resolution of The Troubles. During our study tour of Belfast, we met many women who are continuing the difficult and challenging work involved in translating the Good Friday Agreement into a reality. At a meeting with Republican and Loyalist activists at the Duncairn Community Partnership, a “cross-community partnership built on respect, trust and equality”, we met a Loyalist woman who was so criticized by her own community for working with nearby Republicans — who lived literally across the road — that she was forced to move to another neighborhood. This opposition has not deterred her from continuing her work with her colleagues to bridge the divide, helping to organize joint community celebrations on Halloween, Christmas and International Peace Day.

In Israel/Palestine, their counterpart is Women Wage Peace, a nonpartisan women’s group founded after the 2014 summer war between Israel and Gaza, which calls for an agreement that will be respectful, nonviolent and accepted by both sides. “We will not stop until a political agreement, which will bring us, our children and grandchildren a safe future, is reached,” they declare. One of the highlights of the week-long March of Hope organized in the fall of 2016 by the movement took place at Qasr al-Yahud, the site where Jesus is believed to have been baptized by John the Baptist. Some 2,500 Jewish and Arab Israeli women arrived on buses and were joined by more than 1,000 Palestinian women from the West Bank, calling for an end to the violence and a fair resolution of the conflict. Palestinian women and speakers were also prominent at the closing demonstration of the March outside the prime minister’s residence in Jerusalem. They consciously model their activity on the actions of the Four Mothers movement, which spearheaded the end of Israeli presence in southern Lebanon, which began with the 1982 Lebanon War.

5. Former Combatants/Prisoners

On both sides of the divide in Northern Ireland, people who bore arms were frequently considered heroes defending their communities, though the majority on both sides repudiated the violent actions of the paramilitary groups. When both the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and the Loyalists agreed to disarm and to pursue nonviolent political means to achieve their goals, it was a major step towards a resolution of the conflict. Former prisoners who committed acts of violence now work together to promote conflict resolution in Northern Ireland, and they represent their communities in the Northern Ireland Assembly.

In Israel, people who serve in the IDF (Israeli Defense Forces) are considered the prime defenders of the community, while Palestinians who carry out acts of armed resistance against the occupation — Israelis call them acts of terror and who are imprisoned by the Israelis, are considered heroes in Palestinian society.

Two joint organizations, Combatants for Peace, whose members are former fighters on both sides, and the Bereaved Families Forum, whose members have family members who were victims of violent actions by the other side, are at the forefront of the quest for a resolution of the Israeli- Palestinian conflict.

Thus, there is no doubt that, as in Northern Ireland, former combatants, former prisoners and victims of violence can play a major role in the promotion of a nonviolent resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

6. The Role of the Diaspora

Due to the mass immigration from Ireland during the days of the great famine, there is a huge Irish diaspora, numbering 70 million people — with the largest concentration, 40 million, in North America alone. During the days of The Troubles, some in the powerful American Irish diaspora, both politically and economically, supported the IRA and its armed struggle. The fact that with significant engagement by the Irish Government and others, the Diaspora as a whole moved towards backing a nonviolent, political resolution of the conflict played a major role in providing support for the Republican and Loyalist leaders in the road to the Good Friday Agreement.

In the Israeli-Palestinian context, significant parts of both the Jewish and the Palestinian diasporas have tended to take a more hawkish position on the conflict, but the two diasporas could potentially play a very important role in backing leadership on both sides ready to make the necessary compromises to resolve the conflict. The SISO-Save Israel/Stop the Occupation partnership between Israeli Jews and Jews in the diaspora is an example of such support for a non-violent political resolution of the conflict based upon a two-state solution.

7. The Role of Leadership

Just as with Nelson Mandela and F.W. de Klerk in South Africa, the role of leadership in Northern Ireland was key to resolving the conflict. The 1998 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Republican John Hume and Unionist David Trimble “for their efforts to find a peaceful solution to the conflict in Northern Ireland.” Republican leader Gerry Adams also played a key role in convincing his community to give up the armed struggle and back the Good Friday Agreement.

In the Israeli-Palestinian context, Yitzhak Rabin, Shimon Peres and Yasser Arafat, following the signing of the Oslo Accords, were awarded the 1994 Nobel Peace Prize “for their efforts to create peace in the Middle East.” But that was only the first step. Today, the current Israeli leadership is not ready to do what is necessary to resolve the conflict, while the Palestinian leadership is too weak and divided. We can only hope, and work for the day that the two societies will produce future leaders ready to do what is necessary to resolve the conflict.

8. Fatigue

Everywhere we went, we heard that fatigue was a key factor leading towards the end of The Troubles, and the signing of the Good Friday Agreement. Irish people on both sides of the divide were tired of the violence and the unnecessary civilian deaths, and realized that further violence could not resolve anything.

Apparently the Israelis and Palestinians have not yet reached that point.

A Few Final Observations

We met former Lord Mayor of Belfast Nichola Mallon (2014-15), of the Nationalist SDLP, who is now a member of the Northern Ireland Assembly. She told us that until she went to university she had never met Protestants, despite the fact that they live just on the other side of the road. They went to separate schools and separate after-school activities. It is striking to see the so-called “Peace Walls” that still divide Catholic and Protestant neighborhoods, covered with local patriotic graffiti. There is still a long way to go, but civil society organizations like the Duncairn Community Partnership are leading the way. While they showed us how a local community park is still divided by a locked gate, with one side for Catholics and the other side for Protestants, they also proudly showed us how they assumed responsibility for developing the Delaware Shared Housing Complex, a building where members of both communities live together in harmony.

We also met a number of former IRA activists, some of whom are members of the Northern Ireland Assembly, and others working in civil society organizations. It was very surprising to hear that they were actually inspired when they heard about the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993 by the Israeli government and the Palestine Liberation Organization. “If our allies in the PLO could forgo the armed struggle and sign an agreement with the Israelis,” said one of them, “then we felt that maybe we too could sign agreements with the British and the Unionists”. They also told us that members of the African National Congress (ANC) who had been involved in the negotiations to end the Apartheid regime in South Africa, helped guide them in the negotiations that resulted in the Good Friday Agreement.