I. Introduction

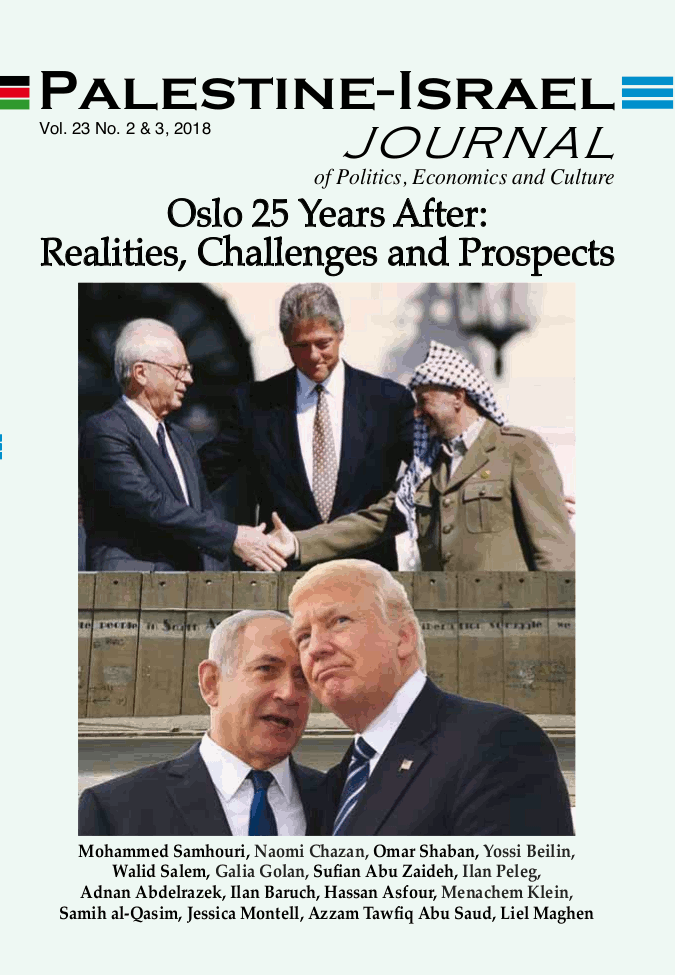

Twenty-five years ago, on September 13, 1993, the Declaration of Principles (DOP) between the government of Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) was signed, and the famous handshake on the West Lawn of the White House between Yassir Arafat and Yitzhak Rabin secured its place in history. Much has been written on why the Oslo peace process has failed politically; yet little attention, if any at all, was paid to its parallel failure to deliver on its promise of a different economic future for the Occupied Palestinians Territories (OPT) of the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip (WBGS).1 Given the vitality of the economic factor in any future negotiated settlement between Israelis and Palestinians, it is worth reflecting on this neglected aspect of Oslo and to draw some useful lessons.

The economic component of the Oslo process was predicated on a simple proposition: that providing international financial support to the newly created interim Palestinian Authority (PA) will help build its debilitated infrastructure and public institutions and attract private investment, both domestic and foreign, so that by the end of a stipulated five-year transitional period from 1994 to 1999, the ingredients for success will be in place and the Palestinian economy will be on its way to prosperity. The prospects of success, it was believed then, would be further enhanced by regional political stability and economic cooperation spawned by the spirit of the 1991 Madrid Peace Conference and the subsequent peace talks between Israel and the PLO.

Twenty-five years later, the picture, at best, is disappointing.

Today, and despite the disbursement of over $30 billion by the international community over the entire post-Oslo period, the Palestinian economy is very weak and in a state of stunted growth, and still highly dependent on Israel for employment and trade. Public institutions — PA institutional reforms of post 2007 notwithstanding — are far from efficient or properly managed, and the Palestinian private sector remains mostly weak and incapable of taking the driver’s seat to generate high and sustained growth rates. Furthermore, Palestinian living standards since the beginning of the Oslo process did not show substantial improvement, with rates of unemployment — especially among educated youth — poverty, and food insecurity remains very high by regional standards. The Palestinian population of close to 5 million in the West Bank (3 million) and the Gaza Strip (2 million), known in the region for its talent and energy, has largely been reduced to welfare cases, especially in Gaza.

What led to this dismal outcome was an overly optimistic and simplistic economic vision that overlooked three critical questions: 1) whether the limited Palestinian control over a noncontiguous and small territory, as produced by the Oslo Accords and further weakened by repeated Israeli closure policies and restrictions on access and movement, was conducive to economic growth and development; 2) whether the PLO, which had no previous tangible experience in economic management at a level of state, was capable of undertaking Oslo’s ambitious economic endeavor; and; 3) whether foreign aid, provided in a grossly inadequate political and territorial setting, would be effective in achieving the expected economic transformation of the occupied Palestinian areas.

With these three critical questions in mind, it is useful to reflect on the state of the Palestinian economy on the eve of the DOP signing in order to see how the Oslo process has largely failed to provide the right setting or the adequate economic policy tools necessary for the PA to deal with the enormous economic challenges it inherited at the time of its creation.

II. The Palestinian Economy on the Eve of Oslo

At the time the Oslo peace process started in September 1993, and the subsequent creation of the PA in May 1994, the Palestinian economy — repressed by the heavy legacy of two and a half decades of the Israeli occupation's restrictive policies — was largely dysfunctional, with distorted productive structure, debilitated infrastructure and high dependency on Israel for wage employment, trade and the provision of public goods. Domestic business environment was burdened by stiff regulations, the absence of supportive financial intermediation, with constrained access to, and utilization of, land and water resources in WBGS. Furthermore, economic and public institutions — other than those that provided education and healthcare services to OPT population — were virtually nonexistent, and trained professionals with skills in economic management and public administration to run such institutions were in short supply. In addition, the Palestinian economy, on the eve of the PA’s assuming power in the Gaza Strip and the Jericho area of the West Bank, was stagnant; regional demand for skilled and semi-skilled Palestinian labor was drying up; and early signs that the Israeli job market was being lost to imported foreign workers were increasingly evident. More serious still, but largely an inevitable outcome of the OPT’s economic stagnation of the 1980s and the economic crisis of the early 1990s, were the socioeconomic statistics indicating rising trends in unemployment and poverty in WBGS.2

That was the state of the Palestinian economy which the PA inherited from the Israeli occupation authorities on the eve of May 4, 1994 and was tasked with the intricate mission to turn it around during the five-year interim period of 1994-99.

The economic challenges facing the nascent PA were indeed daunting. The task was to make a steady shift from an economy that was overwhelmingly dependent on the export of labor services to an economy based on exporting goods; diversify Palestinian's “trade patterns” and “trade partners”; and expand the economy’s production base to allow for such transformation. More specifically, there was a need to effect a gradual and sustained reorientation of the WBGS economy away from its dependence on workers’ remittances towards home-grown sustainable sources of economic growth; open up trade routes and economic channels with the region and the rest of the world and provide for the related trade infrastructure (airport, sea port, roads, etc.) that facilitate direct links with both neighboring and international markets; reform the outdated and complex legal and regulatory environment in order to encourage private-sector investment; set up functional and efficient public institutions that can partner effectively with the private sector; rehabilitate, upgrade and eventually expand basic infrastructure network (e.g., electricity, water, telecommunications, etc); and, perhaps most challengingly of all, provide productive employment to a young and rapidly growing workforce which was facing, at the time, shrinking external demand for its services.

As the experience of the past 25 years show, and for reasons that will be briefly explained below, very little of this hugely ambitious agenda was achieved.

III. Oslo’s Distorted Political and Territorial Setting

To a large extent, the overall setting in which the Palestinian economy had been operating before Oslo (from 1967 to 1993) has not changed much after Oslo. If anything, in fact, it has steadily gotten worse, because the post-1993 Palestinian economy, despite the Oslo process, continued to function under the Israeli military strict control: directly through a series of military orders that were enacted and enforced before and after Oslo, which adversely touched all aspects of economic activities in WBGS;3 and then as a result of the very restrictive political and territorial setting produced by various Oslo agreements themselves.

Worse still, and over a period of a quarter of a century, a whole host of Israeli restrictive policies — considered illegal under international humanitarian law and international human rights law — continued to grossly stymie private business activities in the OPT, repress the development potential of the Palestinian economy and prolong its chronic dependence on Israel for employment, trade and the provision of basic infrastructure services. Today, as a direct outcome of these destructive Israeli policies and practices, the occupied West Bank is territorially fragmented and relentlessly colonized, the Gaza Strip is besieged and subjected to repeated Israeli military assaults, and East Jerusalem is isolated and economically marginalized.4

The grossly distorted setting which led to such grave economic outcome can be briefly summarized by the following six factors which themselves are the product of Oslo’s failure on the political front.5

First, throughout the Oslo period, the Palestinian economy has been operating in the context of a continued colonizing military occupation (which Oslo failed to end), in which Israel had always assumed the upper hand in dictating the course of its development, with Palestinian economic interests, as a result, were constantly compromised in favor of the Israeli ones.

Second, over the entire post-Oslo years, the Palestinian economy operated in an environment of considerable Israeli-imposed web of physical and administrative constraints designed to control Palestinian movement of people and trade; with the nature, scope and intensity of these constraints becoming institutionalized over time.

Third, over the entire 1994-2018 period, Palestinians’ ability to access and utilize their land, water and other critical natural resources; import raw materials and machinery; and freely reach regional and international markets (and at times even their own disconnected domestic markets) had been severely limited.

Fourth, Palestinian economic interests were also compromised by the terms of the 1994 Paris Protocol between Israel and the PLO. The protocol, among other adverse aspects, has preserved the pre-Oslo customs union trade regime between Israel and OPT, and thus continued to obligate the Palestinian economy to operate under the high Israeli cost structure despite the huge income and development differences that existed between the two economies.

Fifth, throughout the post-Oslo era, the Palestinian side lacked a whole host of economic policy tools crucial for short-term stabilization and long-term growth. As a result, the WBGS economy was made vulnerable; Palestinian policymakers’ ability to adjust to frequent fiscal shocks was extremely limited; and their capacity to successfully implement economic recovery plans was highly constrained.

Sixth, because of Oslo’s political failure, the Palestinian economy has been operating in an environment largely dominated by continued conflict conditions, heightened political instability and, at times, renewed violence. This largely counterproductive setting had introduced elements of uncertainty to economic performance and — in the context of high level of OPT dependency on Israel — proved to be very costly to the Palestinian side.

IV. Blame It All on PA Corruption?

Throughout the post-Oslo period, Israel maintained that the chief reason behind continued Palestinian economic troubles is the PA's flagrant corruption. Millions of dollars of donors’ money, the Israeli argument went, have been squandered due to PA mismanagement and embezzlement. While this study does not rule out the presence of corruption in PA institutions, there is a strong reason to believe that this Israeli widely circulated claim, repeated ad nauseam, is highly exaggerated, and pales in comparison with the destructive impact of the discriminatory Israeli policies and practices in OPT throughout the entire post-Oslo period.

One needs only to take a second careful look at the six major underlying factors that this study has identified as the principle reasons behind the dismal Palestinian economic record during the post-Oslo period. The detrimental cumulative impact of these factors is the chief reason behind the continued erosion of the Palestinian economy’s productive capacity, and their excessive adverse weight is the main obstacle that stands in the way of Palestinian economic emancipation and the realization of Palestinian economic potential.

Furthermore, this deeply distorted setting within which the Palestinian economy has been operating during the post-Oslo period is also responsible, to a great extent, for the gross ineffectiveness of the official international financial assistance (estimated by OECD at $31.5 billion between 1994 and 2015)6 to make a sustained positive impact on WBGS captive economy. Once again, the evidence here is irrefutable and can hardly be challenged. As a 2003 UNCTAD report has vividly shown,7 the skewed Palestinian trade structure with Israel has caused a big chunk of foreign aid to the PA to benefit the Israeli economy, not OPT. Using 2002 figures, the report has shown that large Palestinian trade deficit with Israel that year, both as a percentage of OPT total trade deficit (estimated at 70 percent) and as a percentage of WBGS’s GDP (estimated at 45 percent), had respectively, caused some 70 percent of donor funds to be diverted to pay for imports from Israel, and some 45 cents of every dollar produced in WBGS to be channeled to the Israeli economy. Fourteen years later, in 2016, these trade balance percentages were 51 percent and 17 percent, respectively.8 Under these circumstances, it is difficult to see how donor funds injected in the captive Palestinian economy would have a noticeable domestic multiplier effect. “On the contrary,” the UNCTAD report concluded, “a positive income multiplier effect of these funds would be felt in the Israeli economy.”

V. Concluding Thoughts

The preceding discussion has shown how Oslo’s political failure to end the Palestinian-Israeli conflict has led to its failure to provide the propitious setting needed for the Palestinian economy to grow and prosper. The political failure, thus, has engendered an economic failure. With the Oslo process failing on both fronts, and under the overbearing weight of continued colonizing military occupation, the Palestinians in the OPT, 25 years after Oslo, are still denied free access to their national resources; lack the freedom to reach regional and global markets, and are deprived from the freedom to exercise their basic economic rights — enshrined in the universally accepted international law — to make the choices they want concerning their future. The inevitable outcome of all this has been continued decline, de-development and pauperization of WBGS.

As long as this extremely adverse political-territorial setting remains unchanged, no amount of foreign aid will be able to make a sustained positive economic impact in OPT (except perhaps to avert PA fiscal collapse); and no initiative, national or international, to strengthen the Palestinian economy will have the chance to succeed. The failure of PA’s donor-supported State Building Project of 2009-11,9 and the failure of the Quartet/Kerry’s much-ballyhooed $4 billion Initiative for the Palestinian Economy, which was introduced in 2013,10 are a strong reminder of this impossibility. (Note: the PA’s project of state building reached a dead end, and the Quartet/Kerry’s initiative was never implemented).

The implication, thus, is very clear: only an end to the 50-year-long Israeli domination over OPT (which Oslo process has failed to do) and full Palestinian sovereignty over the land occupied in 1967 can enable the Palestinian economy to regain its lost ground, recover the ability to function and grow, and secure the requisite conditions to proceed on the path of sustainable development. Absent that, the economic future of OPT, given its young and rapidly growing population will be too bleak to contemplate.

Endnotes

1 Throughout this study, the terms OPT and WBGS are used interchangeably.

2 On the state of the Palestinian economy in early 1990s and the nature of economic challenges that faced the PA at the outset of the post Oslo period, see the 6-volume study by the World Bank, Developing the Occupied Territories: An Investment in Peace, Volume 2: The Economy (Washington, DC, 1993). Also see UNCTAD, Prospects for Sustained Development of the Palestinian Economy: Strategies and Policies for Reconstruction and Development, 1990-2010 (Geneva, August 21, 1996).

3Israeli military orders continued to restrict the Palestinian economy even after the establishment of the PA in May 1994. The “Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement” of September 1995 has retained all Israeli military orders that were enacted and put in force in WBGS since June 1967. Article 18, para 4.a of agreement states that "legislation [by the PA] which amends or abrogates existing laws or military orders, which exceeds the jurisdiction of the [Palestinian Legislative] Council or which is otherwise inconsistent with the provisions of the DOP, this Agreement, or of any other agreement that may be reached between the two sides during the interim period, shall have no effect and shall be void ab initio."

4For more on the current deteriorating state of the Palestinian economy, see latest reports by the World Bank, the IMF, UNSCO, and the office of the Quartet, presented to the AHLC (Ad Hoc Liaison Committee) meeting held in Brussels on March 20, 2018.

5For a detailed discussion of these six factors and their adverse consequences on the Palestinian economic performance, see the author’s article titled “Fifty Years of Israeli-Palestinian Economic Relations, 1967-2017: What Have We Learned?” Palestine - Israel Journal of Politics, Economics and Culture, Vol.22, No.2 & 3 (2017).

6OECD, Query Wizard for International Development Statistics (QWIDS).

7UNCTAD, Report on UNCTAD'S Assistance to the Palestinian People (Geneva, 28 July 2003), p. 8

8See Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Registered Foreign Trade Statistics Goods and Services, 2016: Main Results (October 2017), Table 1, p. 33, and Table 3, p. 35.

9See, Palestinian National Authority, Palestine: Ending the Occupation, Establishing the State, Program of the Thirteenth Government (August 2009).

10Office of the Quartet, Initiative for the Palestinian Economy, summary Overview (March 2014).