Israeli director Nadav Schirman’s latest film combines a collage of archival footage, re-enactment and first-person narration that, like his first motion picture, Meragel Ha-Shampaniya (The Champagne Spy) (2007), tells a story of Palestinian collaboration with Israeli secret services. There can be no doubt that Schirman has honed his skills as a documentary maker over these past years, perfecting his art and making a number of stylistic decisions in order to get the most out of his astonishing subject material. The Green Prince is a film with a remarkable, gripping plot, narrated in a beautiful and highly distinctive cinematographic style. The music expertly complements the action, the editing is superb, and viewers will find themselves on the edge of their seat throughout. But despite these commendable achievements, The Green Prince is morally and politically dubious, the director’s motives are suspect, and the viewer emerges from the cinema so lost in its tangle of ethical dilemmas that few conclusions can be drawn.

Who is the Green Prince?

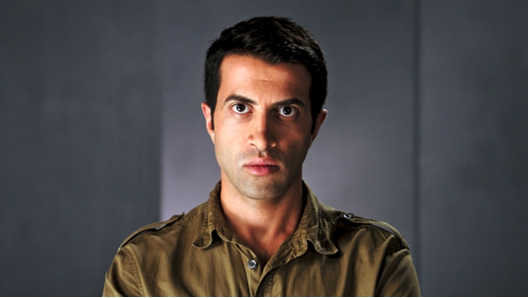

Mosab Hassan Yousef looks directly at the camera as he gives his account of his time as a collaborator.

The film’s title refers to Mosab Hassan Yousef, who himself narrates this astonishing documentary of his life, gazing directly into the camera and eye-balling the viewer as his story becomes increasingly convoluted and absurd. He is the son of Sheikh Hassan Yousef, a founding member of Hamas who was politically vocal and active through the 1990s and who was deeply involved in the Second Intifada in the early 2000s, when Hamas really came to the forefront of Palestinian politics as a viable mainstream party. Hence “The Green Prince” – green being the dominant color of Hamas’ party flag and crest, and Mosab being the son of one of the organization’s primary leaders, or “kings”, so to speak. But it was not the director of the film that came up with this name. Rather, “The Green Prince” was in fact coined by Shin Bet, the Israeli General Security Services and branch of the Israeli Defense Force whose mandate is to gather and provide information on “counter-terrorism operations” in Gaza and the West Bank.

Shin Bet: “A Dark Organization”

The film describes Shin Bet as a “dark organization”, the members of which, apart from their designated head, remain completely anonymous, even to members of the Israeli government – their motto, in Hebrew, is “Magen velo Yera'e”, which translates as “the unseen shield”, or “the invisible defender”.

Nadav Schirman reconstructs haunting interrogation scenes as Mosab and his Shin Bet “Handler”, Gonen Ben Yitzhak, describe their relationship with one another.

Indeed, it was only in 2002 (incidentally, the same year that the IDF began erecting the Separation Barrier around East Jerusalem in an attempt, they claimed, to stem the flow of suicide bombers travelling from the West Bank to Jerusalem and Tel Aviv during the Second Intifada) that the Shin Bet became in any way legally or politically accountable. Prior to May 2002, when the organization was brought under the purview of the Knesset Security and Foreign Affairs Committee, the only governmental monitoring of Shin Bet was financial, ensuring that it stayed within its prescribed budget. Structures designed to check that Shin Bet kept its operations within legal boundaries were limited, and tactically so. The organization would receive an order from the Israeli Prime Minister, such as “find and arrest a terrorist in response to the latest suicide attack”, and, drawing on their ongoing surveillance activities and their various collaborators and informers, they would then oblige.

The Cinema of Collaboration

Palestinian collaborators are, in fact, central to Shin Bet’s operations, and the complex webs and layers of agents and double agents, suspicion and mistrust, that inevitably collects around those who move between two such aggressively opposed political standpoints, have become a recurring theme in the region’s recent cinema. Just last year, the second Palestinian film ever to receive an Oscar nomination, Omar (2013), also grappled with the convolutions of its protagonist as he attempts to negotiate the politics and personal trials of collaboration with Israeli security services. Perhaps this is not surprising, given that the plots of these narratives resemble the compelling traits of innumerable spy novels and espionage thrillers – and in The Green Prince, it is Mosab’s personal story that keeps the viewer hooked.

Culturally, however, collaboration has long been a hugely controversial subject in Palestine, to which the public execution of eighteen suspected collaborators by Hamas in Gaza, following the successful Israeli bombing of several Hamas leaders just a few weeks ago, will testify. Palestinian collaboration with Israel is configured as the ultimate betrayal – of family and friends, on whom the collaborator will necessarily be informing, of course; but also of the Palestinian cause more generally; of any past or future nation; ultimately, a betrayal of history. It should be noted that many Palestinian collaborators start working for Israel against their will for a number of reasons. They might be unable to withstand the pressure of prolonged interrogation and torture; they are often restricted by such extreme poverty – itself a product of the occupation – that Shin Bet’s bribes become a viable economic option; or they may simply be attempting to protect loved ones threatened by the Israeli agency’s illegal operations.

Schirman intersperses the film with archival footage of Mosab and his father during his time as a collaborator.

What is so powerful about this film, though, is that these factors do not underpin Mosab’s decision to collaborate with Shin Bet. Schirman allows the Hamas leader’s son to reveal himself, in his own words, as a psychologically complex, confused, but adamantly self-justified character, who is inflated by the self-importance of his new life as a spy. He sees the betrayal of his father to save the lives of Israelis from Hamas’ terrorist attacks during the Second Intifada as not only unproblematic, but as a project of almost messianic humanitarianism. The film’s only other narrator is Mosab’s Shin Bet “handler”, Gonen Ben Yitzhak, an intelligence officer with a degree in psychology who dealt with Mosab, carefully manipulating him so that he became one of the most valuable assets for the organization’s ongoing and pervasive surveillance operations. The film oscillates between the perspectives of the two men, as they tell the same story in their own words with astonishing, at times even brutal, honesty.

Yitzhak describes the way that he operated as Mosab’s handler, looking directly into the camera as he does so.

A Story of Two Men

What emerges as the film progresses, then, is that the documentary’s subject is not so much the historical emergence of Hamas, the violence and suppression of the Second Intifada, the extra-legal activities of Shin Bet, or any of the many other various waves of politics and counter-politics that form the backdrop to this story through what is often terrifying archival footage. It is rather the relationship between these two men who, so deeply entrenched in a world of lies, collaboration, deception and falsity, come to believe that they find truth only in their relationship with one another. About halfway through the film. Yitzhak actually departs from Shin Bet policy and breaks the organizations strict laws in order to win Mosab’s complete trust and, later on, to save his life. This results in his eventual dismissal from the organization – in a bizarre plot twist, he loses his job because of his relationship with his collaborator. The film shows that the only person Mosab and Yitzhak were ever entirely honest with during this fraught period of their lives was, in fact, each other. A high ranking official in an Israeli intelligence agency designed specifically to monitor and incriminate Palestinians became friends with the eldest son of a Hamas leader, despite the fact that they are figures from polar ends of a political spectrum. The relationship that they forge is as morally muddy and as troublingly complex as the Israeli-Palestinian conflict itself.

A Biased Representation of the Conflict?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the historical narrative underlying this relationship is, though muddy, not exactly neutral. The Intifada is portrayed not as resistance, but as an unprovoked attack on a democratic state by a frighteningly fundamentalist Palestinian group, with footage of hundreds of masked human figures equipped with cardboard rocket launchers and machine guns marching through the streets of Ramallah. These de-humanized masses are framed so as to foreground the only logical deduction that all Palestinians must be terrorists willing to blow themselves up for an unrealizable cause. There is much footage of the brutally violent, horrific outcomes of these suicide attacks but little of the repeated Israeli offensives on Gaza and the West Bank, both before and after these attacks. And as is almost always the case with mainstream depictions of the conflict, the deeper structural violence of the occupation that incites Palestinian resistance in the first place is completely absent. The daily humiliations at checkpoints, the restriction of movement, the loss of land, the lack of access to clean water, the re-naming of streets and re-writing of histories – these slower, everyday modes of violence are invisible in The Green Prince’s representation of the conflict.

There is an unfortunate religious dimension to the film as well, one that has particular currency in light of the current political forces that are shaping our world today. The film is narrated entirely in English and Hebrew, with Arabic relegated to the occasional subtitle, despite the centrality of its titular Arab protagonist. Throughout, Mosad is portrayed as a particularly unenthusiastic Muslim, remaining on the religious peripheries of Hamas despite his father’s own rigorous belief. Indeed, Yitzhak and Shin Beit on many occasions encouraged Mosad to be “more Muslim” so that he might penetrate the organization further and avoid suspicion. But this would have to be faked, of course, because were Mosad to actually succumb to the heady ideology of Islam he would become like all those others portrayed on screen, a potential suicide bomber – so the film’s discourse goes. Mosad’s cooperation with Israel, his interior or cultural “whiteness”, and his anti-suicide bomber rhetoric (the most frequent argument which he cites as a justification of his actions and one that, if it did not seem that he were fooling himself, would certainly be a commendable one) are all conflated so as to boil the ultimate political backdrop back down to the binaries of good and evil from which it had, at first, so fruitfully departed. As if this were not obvious enough, after fleeing the West Bank and Israel to seek asylum in the U.S., Mosad converts to Christianity, a move that coincides with, if not directly winning him, his freedom.

Schirman uses highly stylized reconstructed footage – in this case Mosab being picked up by Shin Bet agents as seen through a drone’s surveillance camera - to build the atmosphere of tension throughout the film.

Mostly Grey

Despite these problems with the film, there is no doubt that The Green Prince is a must see for anyone interested in the recent history of Israel and Palestine, the politics of collaboration, or simply those who like a good spy thriller. Even well-informed viewers will find themselves wrong-footed by the tangle of ethical and moral convolutions from which this narrative is comprised. If there is one point that can be drawn from Schirman’s latest offering, then, perhaps it is this: that no matter how sure of your own opinions on the conflict you thought you were – no matter how black and white you thought some aspects of it could be – there is always a story that can reduce these oppositional certainties to an ambiguous grey. Schirman has found such a story and presented it to his viewer in a documentary style that seems to shrug its shoulders, saying with a convincing flippancy: “I am not here to pass judgment, only to tell a story. It is up to you, viewer, to make of this what you will!”