In my time studying and researching the conflict in Israel and Palestine, as an Australian, I cannot help but draw comparisons between Australia’s history and Israel’s history, especially in regards to the history of the indigenous Aboriginal population in Australia, and indigenous Palestinians, whose land has either been absorbed into or occupied by the State of Israel. While the histories of the two nations are by no means identical, there are some interesting parallels that can be found.

Terra Nullius

When Captain Cook arrived on Australian shores in 1770, he had been sent by the British to establish a penal colony for those convicts who could no longer be sent to the United States due to the American War of Independence from Great Britain, and there was no room for them in British gaols. There was no concept of any deep or historic connection to the land, only British pragmatism and imperialism. Despite the presence of Aboriginal tribes on the land, Britain claimed the principle of terra nullius, that is, that the land did not belong to anyone, and declared the land as their own. This was based on the claims that the Aboriginal people did not have a political or legal structure that the British could understand, and therefore they had no partner to sign of treaty with. There was no consideration that the Aboriginal tribes had a different kind of legitimacy in their claims to the land: fire-burning methods of land maintenance, a hunter-gatherer lifestyle, spiritual traditions and connections with the land, and a political and social system based on tribalism.

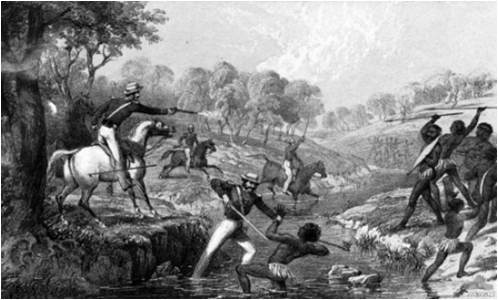

British police and Aboriginal warriors during the Slaughterhouse Creek Massacre of 1838 (Image: Wikipedia)

For Jews in Israel, however, there is a historic and religious connection to the land that spans back thousands of years. There is a Jewish claim that God promised the land of Israel to them, and that throughout history, there has always been a Jewish presence in the region. The importance of Jerusalem as a holy place for Jews is tantamount in the claim that the land should be a Jewish state as well. These claims, however, overlook the parallel arguments made by Palestinians who have a historic and religious connection to the land too. Jerusalem is also a holy place for both Christians and Muslims and, while not historically known by the name ‘Palestinian’, a significant Arab population has lived, worked and connected to the land for thousands of years as well. The population may not have existed as part of a recognised sovereign state under any national identity, but this does not negate the rights of the people to claim the land as their own: a land whose population does not comply with the Westphalian system of sovereignty, does not mean that it is a land without a people.

Settlement and Occupation

Once the British had consolidated their presence in Australia, they began to move Aboriginal communities off their land, as they did not consider the land to be legally ‘owned’ by any of these tribes. And so began the settlement of ‘free settlers’ from Britain onto Aboriginal land, bringing with them diseases that killed many Aboriginal communities, as well as alcohol, tobacco and drugs that the Aboriginal people had no tolerance for.

Numerous laws passed at the turn of the 20th century saw the legalising of the forced resettling of Aborigines onto reserves and the removal and segregation of ‘half-caste’ children from their families, known as the ‘stolen generation’. It was only with the amendment of the Australian Constitution in 1967 that Aborigines were included in the census and had legal rights under the Commonwealth, such as the right to vote. In the remainder of the century there was a reversal of racist policies and the development of inclusive legislation for Aborigines, including property rights and compensation for those forced off their land.

This is comparable with the ‘right of return’ claims of Palestinians who left their homes during the 1948 war and assert their right to return to their homes and land now that the war is over. Those Palestinians who did not leave their homes (who make up 20% of the Palestinian population) and now reside in Israel do have civil rights as Israeli citizens. However, Palestinians who reside in the West Bank and East Jerusalem do not have these rights, as they are not considered Israeli citizens. Without Israeli citizenship, 80% of the Palestinian population are without basic rights and remain under Israeli occupation. The refugees’ right of return is also a divisive issue in the peace process, as Palestinian herald international law in support of their claim, but Israel existence as a Jewish state would be jeopardised by an influx of Palestinian refugees. The issue of refugees’ right to return is an important issue to address in any peace process: Palestinians view their return as an inalienable human right, but Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu dismisses these claims as illegitimate and unrealistic.

The UNRWA al-Am'ari refugee camp in Ramallah, with a painting of the Dome of the Rock symbolising the desire to return to holy sites in Jerusalem (Photo: Elizabeth Lawrence)

Furthermore, Israel continues its occupation of the West Bank and has erected hundreds of settlements and ‘settlement outposts’, relocating over half a million Israelis into occupied territory, in violation of international law. In order to accommodate these settlements, Israel has reinterpreted land laws to declare private Palestinian land as state land, expelling Palestinians and also Bedouins from their homes.

Human Rights

These settlements violate numerous human rights for Palestinians, including the right to property, equality and the freedom of movement. This is reinforced by the erection of the ‘security barrier’ (also known as the ‘separation wall’) that severs many Palestinians from their families, land, workplaces and holy sites. Just as Aborigines were unable to vote in federal elections before 1967, still today Palestinians living in the Occupied Territories who do not hold Israeli citizenship (which is becoming almost impossible to gain due to various stringent measures implemented by the Israeli Interior Ministry) cannot vote in the Knesset. This is even true for those Palestinians with permanent residency status living in East Jerusalem, despite Israeli claims that it has unified East and West Jerusalem, making East Jerusalem part of the state of Israel.

The security barrier that divides the Palestinian village of Abu Dis from Jerusalem (Photo: Times of Israel)

While Australia has made headway in recent times in closing the gap between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians, Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s recent comments regarding the “lifestyle choice” of indigenous communities to live in isolated rural areas has received huge public backlash. The Abbott government claims it cannot justify the expense of providing services to these isolated areas, and so will make a one-off payment to the communities who will have to relocate in order to receive government services. This type of coercion to move Aboriginal communities off their land by means of government policy has disturbing similarities to the government policies that removed the ‘stolen generation’ of children from their homes on Aboriginal land, and disregards the cultural, spiritual, physical and historical connection between Aboriginal communities and their land.

Protest in Melbourne, Australia against the closure of remote Aboriginal communities (Photo: ABC Australia)

The Israeli government has a policy towards indigenous Arab Bedouins of the Negev desert that is comparable to Abbott’s “lifestyle choice” policy. Instead of forced closure of communities, however, the Knesset declares Bedouin villages as ‘unrecognized’ and therefore does not provide basic state-run necessities such as water, electricity, roads or education to these communities. Furthermore, in June 2013, the Knesset approved the Begin-Prawer Plan that would see tens of thousands of Bedouins forced to relocate and their villages destroyed. Though the controversial bill was halted in December 2013, there have been reports that demolitions of Bedouin villages are occurring nonetheless.

Moving forward

Of course, Australia and Israel’s historic and current circumstances are not identical, but both governments have an obligation to uphold and protect the rights of all people they are responsible for, and to respect their history and culture. As it stands, both countries are falling short of these obligations: Australia still struggles with its colonial past, and Israel’s policy in the occupied West Bank has been likened to that of apartheid. Both Australia and Israel need to acknowledge past wrongs and move towards reconciliation and peace with their indigenous populations.