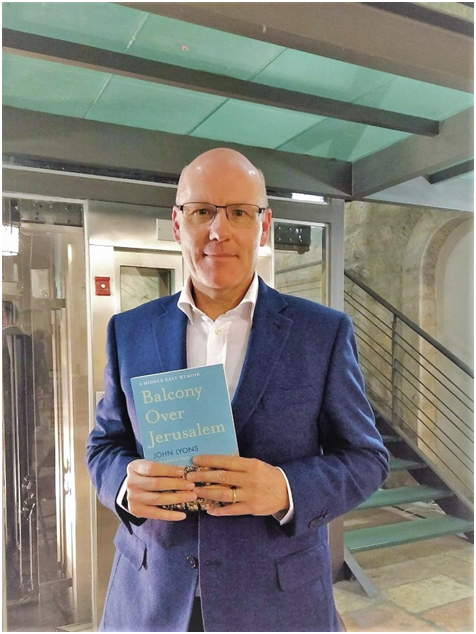

On Thursday, December 14th, 2017, John Lyons presented the product of a 6-year-journey, his memoir on the Middle East, at the invitation of Mahmoud Muna, of the Educational Bookshop. The event took place at the Palestinian Heritage Museum and was well-attended.

After a series of interviews with Israeli government officials like Shimon Peres and Ehud Ormert, but also with Hamas and Hezbollah leaders, and close contacts with the Israeli army, Lyons has processed all his experiences in a 400 page-long memoir about conflict, hope, war and the people that live the Middle Eastern entanglements. Those six years were shared with his family, his wife Sylvie Le Clezio, a photographer and documentary filmmaker with whom he wrote the book, and their son Jack. As they observed life in Jerusalem below their balcony, he decided early on to give an honest account of what was going on in Israel and the occupied territories, without choosing sides.

The question was: What does Jerusalem and the Middle East look like through the lens of a foreign reporter?

Rabin’s hesitant handshake with Arafat aroused his curiosity

Send by The Australian, one of the Australia’s most widely read newspapers, he early on encountered a pressure from home, to be careful how to write about Israel. “We were pressured to not tell what was going on here,” he says, meaning the fear of his editors to be called anti-Semitic by groups from home that supported Israel. But this did not seem to influence him. “The more I got told to not tell the truth, the more I wanted to go back and see for myself.” His interest in the conflict at all came from somewhere else: as a young correspondent in Washington D.C. he had witnessed the famous handshake between Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat on the White House front lawn in 1993. The story behind this handshake and the celebrated Oslo agreement generated his curiosity. It had been Rabin’s long hesitation before shaking Arafat's hand, and Clinton’s small push, that made him think: why had it been so difficult for two people to reach a peace agreement, something that seemed so obvious to an Australian like him?

Lyons came to Jerusalem in January 2009, just at the end of the Gaza war. From his “balcony” he then covered the major events that took place in the Middle East. During his report on the uproar against Egypt’s former dictator Hosni Mubarak in January 2011, he experienced the brutality and lawlessness of Cairo on the brink of revolution while being kidnapped by the military. By chance, he managed to be liberated through the help of Australian and German government officials - only to witness the killing of another Egyptian prisoner by an angry mob, he described as “one of the worst things I’ve ever seen.”

Observing the treatment of Palestinian minors in military courts

Besides reportages on the turmoil of Middle Eastern countries, his memoir mainly focuses on the life of Palestinians and Israelis in Israel, especially in Jerusalem. Being confronted with angry French and Palestinian parents at his son’s school, suspicious friends and his own journalistic naivety, Lyons paints a memorable picture of a city torn apart, filled with distrust and friendship, with glimmers of hope often ignored and trampled on. Having lived these experiences through his family's daily routine, he also explored the grievances on a different level, by visiting Israeli military courts. It is important to know that Israel is being criticized for having two judicial systems, one in Israel and the other one applied by the Israeli military on the Palestinian population in the territories. What he and his wife Sylvie observed during their work in the court was “a front line of one of the oldest conflicts in the world, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. It is Israel’s conveyor belt of justice, but it is a world away from Israel.” The treatment of Palestinian minors by the IDF, the Israeli army, became one of their major projects. He tried to approximate truth by using official documents handed to him by the Israeli military with whom he had friendly working relations. “They are reliable sources,” he says. Once, he heard from a connection at the Ministry of Justice that certain officials had had a dislike for his reports about the Palestinian minor convicts – with the thought of banning him from the court. Realizing that a working ban for a foreign journalist in Israel would bring him a cover story back in Australia, he confronted them with the rumors – and as a result they allowed him to keep his working permit in the military courts.

Maintaining his journalistic integrity

Soon, Lyons and Le Clezio encountered a strong resentment and pressure from home - initiated by Israel support groups who wrote his editor calling upon him to stop reporting negatively about Israel’s policy in the occupied territories. - In Lyon’s eyes this endangered his journalistic position as an observer, who reports what he sees, not what he is told to write. His stories describe the fears that journalists face when reporting about Israel: having projects cancelled at the last minute or editors calling for a different outlook in the article - a constant risk of perverting the truth, of shaping it into the direction wanted, whether it is pro-Palestinian or pro-Israeli. The challenge of giving the whole picture stays enormous for foreign reporters and is complicated through budget-cuts – many newspapers can no longer afford to maintain a regular correspondent in Jerusalem or even Israel.

When asked about President Trump and his decision to officially declare Jerusalem to be the capital of Israel, Lyons seemed to have waited for the question: “Trump gave nothing in return, he only took it. He is illogical when talking about a two-state solution. He is like a judge in a bad divorce. The judge tells the husband that he can have the house and in a couple of months we can decide about the furniture.”

Through his memoir, Lyons story achieves something a one-week-report that is done during times of protest could never capture: depicting normal life within the conflict, a way of dealing with the occupation, the missiles, the random destruction of houses or a fight with a new neighbor, while giving personal reports about other Middle Eastern situations which add to the story. Through his lens, the layers and stratifications of the conflict seem clearer – and also more numerous.

John Lyons and his book “Balcony Over Jerusalem”