‘Gaza is an onion with many layers.’

Don Macintyre (former Independent's Jerusalem bureau chief who has made 80-100 trips to Gaza since 2004) and Stephen Farrell (current Jerusalem bureau chief of Reuters, who has reported on Gaza since 2000, and has also co-written a book on Gaza) discussed Macintyre’s new book, Gaza: Preparing for Dawn, at a book launch which took place at the American Colony Hotel in East Jerusalem, under the auspices of the Educational Book Shop. Throughout, Macintyre refrained from making predictions, apologising for his ‘inadequate’ responses. Nevertheless, a profound loyalty to accurately represent the people of Gaza and an optimistic outlook on the people, if not the politics, came through.

The book begins in a Shakespeare lesson in the classroom of a girls’ school, and a Nuseirat refugee camp performance of King Lear. The version of ‘Romeo and Juliet’ they are studying has Hamas and Fatah as the Montagues and Capulets -without reconciliation at the end. It is done without support from the British Council – an act that it is not just an economic, but in many ways also a cultural boycott.

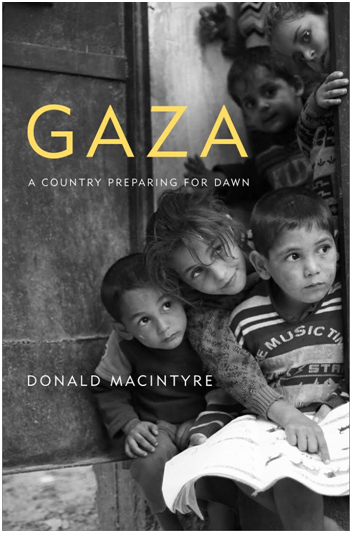

For Macintyre, the most emotional moment was evident in the question asked by a Gazan woman herself who was at the launch: why the picture on the cover? Why portray Gaza as a bleak prison, when it has so much more spirit than the lifelessness portrayed in the mainstream view? This is what Gazans need to fight against; Gaza is a source of life and home, not just a political tool for Israel, Egypt, the Arab countries or the international community.

This is not to understate the paralysis of the blockade and the devastation of the political instability on the lives of ordinary people in a place that is ‘more economically, spiritually and mentally depressed than ever before’. Indeed, as Macintyre pointed out, there is a whole generation growing up in Gaza who have never known anything other than the blockade, met a single Israeli or left those 365 square kilometres; yet it is exactly this which has kindled the Gazan identity, distinct from Palestinian in general. Emphasis was on the potential of vibrant life that could be realised if the blockade were to end. Farrell pointed out the unexploited 34 miles of coast, natural gas field, and the ‘sumud’ (steadfastness) of the fantastic entrepreneurial and talented people who could be a tremendously successful driver for whatever eventually emerges out of the mess. He told of the near disbelief of young Gazans when he recounts his first experience of their home: the gleaming international airport, graced by names such as Hilary and Bill Clinton, and Nelson Mandela, which ‘seems now like a ghostly mythic memory’. A blown up picture of a passport stamped by the airport that hangs on a restaurant’s wall is a mere relic of the past. Gaza, he proposes, must not be treated as a charity case; it needs investment in development to reclaim its dynamism.

The question of blame

Despite provoking a laugh, an audience member’s question seeking a hierarchy of blame was one the room was tangibly keen to hear. It’s an Israeli Occupation, came the answer, and it’s impossible to dance around the fact that they’re the primary cause. Yet others are not exempt; one only needs to witness the desperation when Rafah is open and see the sums of $2000-$3000 in bribes paid to get out, to attribute significant responsibility to Egypt. To give Gaza to Egypt, as Trump’s ‘peace plan’ apparently calls for, would, judging by their handling of Bedouins in Sinai, be a disaster.

Palestinian governance bears responsibility, too, although the toxic struggle for power between Hamas and Fatah is entirely ‘circumscribed by Israel’. It was an ironically fitting day to hold the event; only a few hours earlier, the most senior person to be attacked since 2007, Prime Minister Rami Hamdallah, escaped an explosion on his visit into the Gaza Strip. It was, in Macintyre’s words, ‘a physical symbol of something that had been apparent for many years’: the failure of Hamas and Fatah’s cooperation. This ‘very very painful’ reality expresses itself repeatedly, for example in December, when Hamas decided that it didn’t want to hand over responsibility for the Ministry of Transport to the Palestinian Authority (PA).

The book launch at the American Colony Hotel on March 13, 2018 (Photo: Leah TillmannMorris)

Farrell accused the international community of pushing Hamas to be part of the 2005 elections without any plan for when they did win. It’s hard to know whether Hamas’ bedrock of support still exists; even unmanipulated polls may be inaccurate as those polled attempt to not jeopardise the election by showing support for a ‘terrorist’ organisation. As Macintyre put it, ‘Gaza is an onion with many layers’. More generally, the international community has been deficient in pressuring Egypt and Israel, for whom Hamas’ endurance indicates the blockade has not been a ‘success’ for them either. It has been even more hopelessly deficient in donating funds to prevent the humanitarian crisis predicted by 2020.

Part of this may be due to the way Gaza has been pushed out of the world’s consciousness of the Middle East by Syria, ISIS and Iraq. A recurring theme was the difficulties faced by journalists in Gaza; both externally and internally. Macintyre rejects the claim (often made by Israelis) that Gaza is over-reported. During operations, Westerners may have seen pictures of Gaza on their TV screens every night, but between them, hardly anything. This, he says, is a missed opportunity: if more attention was paid to Gaza in the times of so-called peace, pressure on Israel and Egypt to end the blockade could build. Macintyre described his feeling of privilege in his continuing ability to go in and out once that was stopped for Israeli journalists in 2006/7. The flow of witnesses has become very restricted, and the outside world’s attention relies on a tiny number of correspondents.

Preparing Gaza for its dawn involves more reporting on the ‘peace-time’ situation, so that the world doesn’t forget it exists. It needs more than just the aid required to divert the humanitarian crisis predicted for 2020: it needs investment in its economy and culture, so that it can commit to strengthening its people and their position. It needs recognition for when the darkness lifts.