Alistair Little: First of all, I would like to say I am very conscious that you are on a painful journey yourselves, in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. So I come here with humility. I don’t come here to give you advice; we are not that arrogant. We simply want to share the story of our very personal and very human journey, and hopefully some of what we share will be helpful to you.

I grew up during the conflict in Northern Ireland, in a small town outside of Belfast. In those days, if I had got a chance, I probably would have killed Gerry because he was on the side of the Republicans. My hometown was completely destroyed twice by the bombs of the Irish Republican Army (IRA), and every night we would be involved in riots against the Nationalists. When I was 14 years old, my friend’s father, who was serving in the British Army, was shot dead by the IRA. I remember crying at his funeral and feeling embarrassed because that is not what boys are supposed to do. They are supposed to be strong, and are not supposed to show emotion. When I left the funeral I vowed to take revenge. So at the age of 14, I joined an extremist paramilitary organization called the UVF — the Ulster Volunteer Force.

During those years I lived in a housing estate that was 100% Protestant, Unionist and British. This means that I had no significant interaction with anyone outside of my own religious, political or cultural background. I would listen to our political and religious leaders saying that our way of life was under threat, and I believed that we needed to stand up and defend it. I also believed that God was a Protestant, that He was on our side because we were the good guys and people like Gerry were the bad guys. As a result, I started demonizing and dehumanizing the other [Republican] side. “They are less than human,” I thought. “Their suffering is deserved and ours is not.” For me this was a question of “us or them”: If you kill one of us, we will kill two of you; if you kill five of us, we will kill ten of you. I had no consideration for the suffering of the enemies and would have carried out attacks against them without hesitation.

My views only began to change when I was imprisoned, between the ages of 17 and 30. During that period I started questioning whether violence was the right means to achieve our goals. I realized that the cycle of violence was endless, that we needed to find a different way forward, or else young men and women would continue to go to prison or to die and to be carried to the graveyard. I recognized that the killing needed to stop and that I needed to understand the suffering of the enemy. To me, having these thoughts felt like a betrayal, as if there was a little voice in my head preventing me from feeling these things. The young Alistair would have killed the Alistair sitting here today for saying these things.

Let me tell you about an incident a few days after the death of the IRA hunger striker Bobby Sands. That day I got angry with the prison guards because they were laughing and one of them said he could not wait until the next Irish Nationalist died. And I responded to the guard: “Bobby Sands has more courage than you will ever have.” Later that evening I was wrestling with myself. Why are you defending Bobby Sands? Why are you speaking up for the enemy? Then I asked myself whether I could I starve myself to death for something I believed in. Being young and boastful, I thought: “Of course I can, anything the enemy can do I can do better.”

But in my heart I knew the answer was probably “no,” because it takes a special type of human being to starve themselves to death for something they believe in. This was probably the first time I recognized Bobby Sands’ courage and thus his humanity. This incident was one of many catalysts of change which helped to rekindle my own humanity that had been desensitized and dehumanized. So I began my journey of trying to understand the human cost of violence and began to run workshops bringing together people from different sides of the conflict. I wanted people to share their stories, without talking about who is right and who is wrong, what you did and what we did. I just wanted to encourage them to listen to a different story, to a different truth, without being frightened, so they will realize that truth has many faces and one truth does not cancel out another one. It was a painful and lonely journey. I constantly heard that voice in my head saying, “You’re a traitor, betraying yourself, betraying your family, betraying the cause.”

Eventually my work took me to different parts of the world: Afghanistan, Croatia, Kosovo, Bosnia, South Africa, and to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. During my travels I realized that it does not matter what the color of your skin, your nationality or religion is, your blood has the same color and your suffering is the same. And so I became less interested in the politics and more interested in the human story, in trying to connect the heart with the head. There is often a huge gap between what we think and what we feel, so that is what most of my work today focuses on. I have learnt a tremendous amount from being around Israelis and Palestinians, specifically from the people in Combatants for Peace. And I have learnt a lot from Gerry, my enemy. We are actually friends today, which is not how we set out. We still have huge differences, but I trust him with my life. I have been in his home; he has been in my home. He has a different view of the world than I have, different aspirations and dreams, but his aspirations and dreams don’t threaten mine. And I will stand up for his right to have those differences.

Gerry Foster: I come from an Irish Catholic background and grew up in a housing estate in West Belfast, where battles between the IRA and the British would go on for hours every day. My two older brothers, who were just 16 and 17 at the time, were involved in these gun battles, along with the other young lads and girls on the estate. There was no secret army. We all knew who these people were even when they were wearing masks. They were our neighbors, our families, our friends. Seeing my older brothers armed in the streets, fighting the British, I felt that they were heroes.

Even with the gun battles, even with the British raiding your home, sometimes two or three times a day, life went on, you still went to school, you still played outside. We grew older, became teenagers, our lives changed, but one thing remained the same. The British were there all the time, you would see them on the way to school, and you would be stopped and searched on the way to the city center.

I take personal responsibility for what I did and what I was involved in. No one forced me to do anything. I was involved in protests in support of the hunger strikers. Then I took the conscious decision to get involved in the armed struggle and joined an organization called the Irish National Liberation League (INLL). My only reason for joining them, as opposed to the IRA, was that they were more active in the housing estate where I lived. You would see them every day, with their arms, attacking the British. In my mind, it was quite simple. As Alistair put it: We were right; they were wrong. If the enemies were using violence, then we had every right to also use violence as a tactic.

When I joined the INLA I was 18 years old. At 19 I was captured after planting a bomb in the Belfast city center. I remember driving into the town with another young lad in order to plant a bomb. We were planting the bomb at the Unionist party headquarters, the cream of the pro-British political establishment and the thought of killing them all was something I felt excited about rather than horrified of. I felt no remorse and have no memory of the people around us although there must have been civilians on the street that day, as the biggest bus station in the North of Ireland was beside the building.

Fortunately, or unfortunately, we were seen planting the bomb, and they were able to evacuate the building before the bomb went off. I went to prison for that bomb, and that is when I first became politicized. I was actually shocked to find out the IRA was a “Communist” organization! That is how little I had thought about the politics beforehand. When I left prison at 25, I once more got involved in the conflict. My involvement was probably mostly about showing to my friends that prison had not changed me, that I was still ready to do illegal things. I was arrested again when I was 29 and was released a second time in 1994 at the time of one of the ceasefires.

When young people get in trouble, a lot of people say: “Don’t blame the child, blame the parents.” You should know that my dad hated what I was involved in. These were his last words to me before I was captured. He shouted: “If they kill you, I will bury you. But if they catch you and you go to prison I will never come to see you.

And he never did. That is how far removed I was from my father, and I know it was the same for Alistair. My dad is now dead, but he was buried very close to where the enemies are buried in the cemetery. So I cannot go to one without going to the other. Once I was reading the names of friends who had died; they were young men, only 22, 23 or 24. I realized how horrible it is that young people are usually the ones to die in the war. I started to feel that I was betraying my dead friends and betraying myself for working with Alistair. So sometimes when he gave a talk to a group of people I only came along to prove to the audience that he was wrong about the conflict and I was right.

All journeys are different. Unlike for Alistair, my time in prison was just a continuation of the struggle. I only started seeing things differently when I participated in a residential workshop with families of British soldiers who had been killed in Ireland. It was quite a difficult and emotional experience. When I left, I was wondering why these families’ crying had upset me so much. “I have enough problems of my own,” I thought, “I don’t want to know about their pain.” But I could not forget what I had seen, I realized this was the first time in my life I had genuinely seen the hurt and pain of the enemy — the hurt and pain that we had caused them.

This was when I started thinking about the human cost of the conflict. I no longer wanted to score points in debates. I started to talk from the heart, about how we could help people who have lost loved ones, not on a political level, but on a human level.

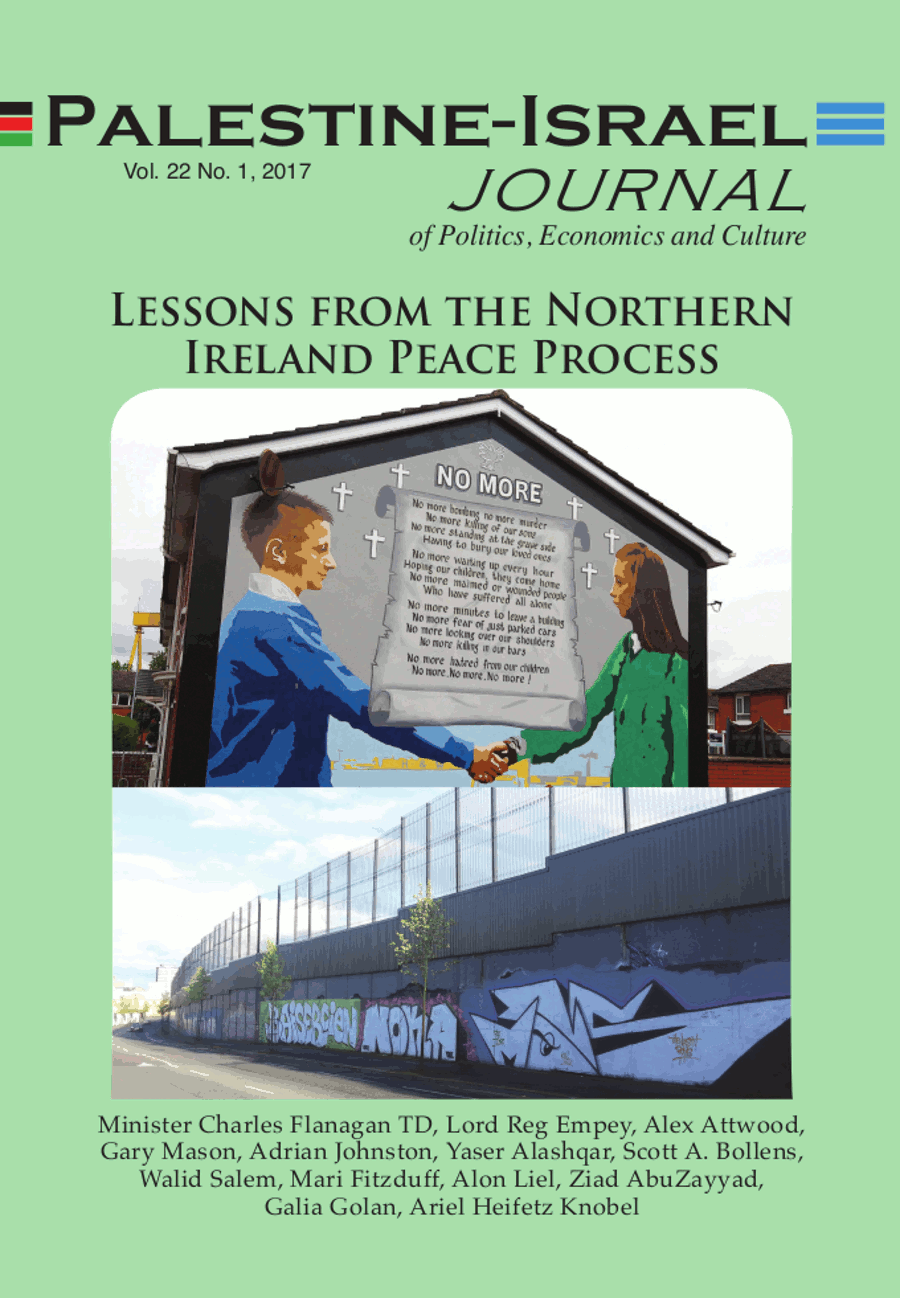

Unfortunately, despite the peace process on the political level, today there are more walls in Belfast then there were during the conflict. They have built 40 new walls since the ceasefire. Alistair and I have a lot of issues with the political process, but despite this we recognize that the peace process has saved lives and has made Ireland a better place.

AL: The reason why there are more walls now is that people realized they would have to give up things in exchange for peace. I am not talking about beliefs and principles but about terms of the power dynamics in Northern Ireland. After the conclusion of the peace, a lot of people withdrew back to their own communities out of an irrational fear. One of the problems with the peace process was the unrealistic expectation that, with the signing of a piece of paper, the emotional and psychological wounds would heal by themselves. I do not think I will live long enough to see these wounds healed, but I am okay with that. I am working for my children and for their future. I do believe that my dreams will come true and that our society will grow to respect one another and to see that no one can live alone, no family, no country and no nation can survive alone. We need each other.

A lot of people have a misconception about peace or reconciliation. For me, it all began with that deep belief that I didn’t want violence to be a part of my life anymore. Once I knew that, I knew [that] I had to engage with the enemy and that it would not always be pleasant. Part of the peace process in Northern Ireland, or of any reconciliation, is about having your enemy vent their anger on you as I did on my enemy. That is part of the journey, because initially people are suffering, they are hurt and frightened, but eventually you move beyond that, beyond what Gerry said about simply wanting to score political points. You might start to make eye contact; you might agree with what they said, even if you are not voicing it openly. And then, after months, you get the courage to say: “I agree with what Gerry said.” There will be those on your own side calling you a traitor, or saying that you are weak, because they are frightened, too; they are hurting and have lost loved ones. I understood that part of the journey is about withstanding those attacks and being accused of those things. That is why I said it can be lonely at times.

Eventually you reach that point where you find the courage to say: “I like this person, my former enemy, as a human being, and I agree with him.” Often the peace is every bit as risky as the conflict itself. It is still difficult; it is still painful because we never lose our memories and the emotion that comes with it. We just learn to deal with it better.

GF: Alistair’s journey started in prison, long before mine. When we met, he was further along his path. I fell into this accidentally, reluctantly. I didn’t want to listen to these people. I didn’t want to hear British soldiers’ stories. At times I wanted to walk away from it, because I really did feel a sense of betrayal, really did feel that this was wrong. But I also heard that voice saying: “The violence needs to stop, the armed struggle needs to stop. We need to do something different.”

I don’t know where we are going with this process; I just know where we came from, and I don’t want us to go back there. Sometimes the workshops we run are badly organized and badly run. They reinforce perceptions; sometimes things don’t work out. Some of the work we do is with young people. We are encouraging them to get involved in organizations that won’t pursue violence. And the sad thing is, the only reason we have influence over these young people is because of our own violent past.

AL: When I was involved in the conflict, the religious dimension was stronger. As the crisis moved on, it became more of a cultural conflict, a conflict about identity. Religion only became important in the context of the ceasefires or the disarmament. Religious leaders on both sides of the community were seen as honest brokers and were trusted by both sides of the community to oversee the decommissioning.

There is a significant number of people who refer to themselves as Protestant as a purely cultural identity. Then there is the question about the passports — in Northern Ireland you can have an Irish or British passport, so I can have both of them if I chose. Gerry has a British passport, but in southern Ireland you can’t have a British passport.

Gerry Foster: I firmly believe in letting everyone be what they want to be. Whether they want to be Palestinian or Israeli, so be it. If they want to be Palestinian, let them. As Alistair said, I have a British passport; it means nothing to me. It’s a document I need to get from A to B. It’s not even my nationality, because I feel Irish. You know what I mean: Be what you want to be. Choose your own labels; don’t let anyone else do it for you.