There were clearly many problems with the Oslo Accords. In fact, one of their architects, the late Dr. Ron Pundak, believed that a major flaw was the absence of an “end game.” Both sides had difficulty justifying potential sacrifices without the promise that the final result would meet the Palestinian objective of establishing an independent state and the Israeli objective of ending the conflict.

Such ambiguity greatly facilitated the spoiling actions by opponents of the Accords. Indeed, the interim nature of the Accords itself allowed spoilers time to mobilize and take action. The situation was further aggravated by Israel’s refusal to freeze settlement construction, its continued responsibility for the settlers’ protection, and its increased interference with Palestinians’ freedom of movement within the West Bank as it built by-pass roads and withdrew from certain areas.

All of this eroded a process that was already suffering from delays in implementation in the absence of any (local or international) monitoring mechanism. Finally, the violence of the Islamists that plagued the process from day one exacerbated the destructive ramifications of the Oslo venture.

A Positive Turning Point

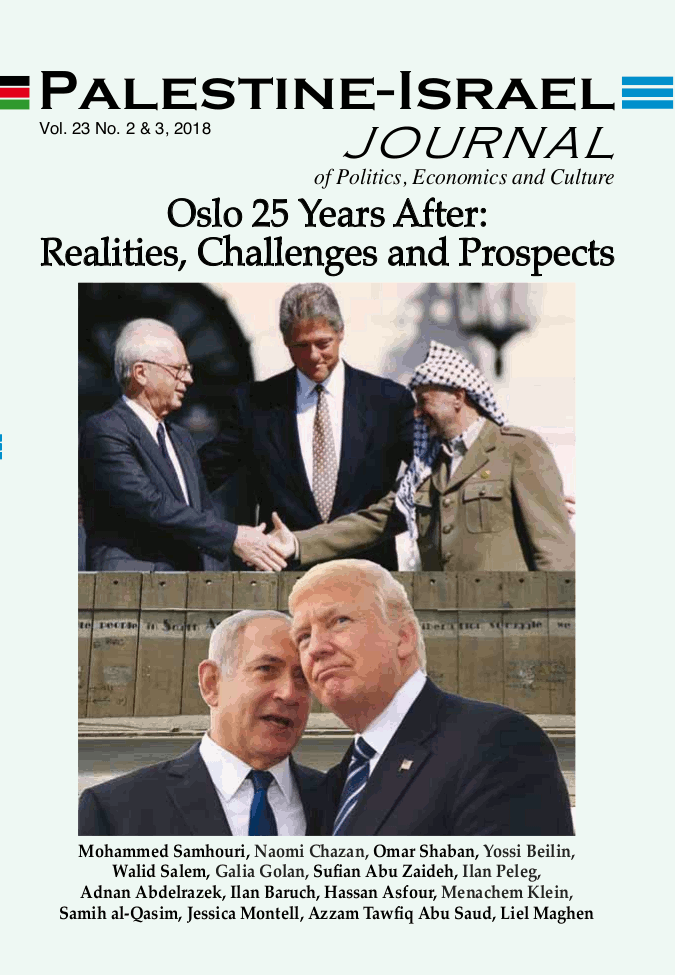

Nonetheless, I would argue that Oslo was a positive turning point of mammoth dimensions in the history of the conflict and also witnessed an unprecedented period of positive developments. The formal letters of mutual recognition written by PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat and Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin constituted an irreversible step. The PLO had already taken this step — announcing its recognition of Israel’s right to exist within secure and recognized borders — in the 1988 decision of the Palestinian National Council (PNC). But putting it in writing (“Israel’s right to exist in peace and security”) directly to the prime minister of Israel in September 1993, together with the promise to abrogate any statements to the contrary in the PLO Charter (a promise fulfilled at the April 24, 1996 PNC meeting), enshrined this recognition in a binding document.

For its part, Israel was less forthcoming. It did not recognize or even mention Palestinian rights, to a state or anything else. Nonetheless, by recognizing the PLO as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people, Israel not only eschewed past attempts at finding alternatives to the national liberation movement of the Palestinians but also officially acknowledged for the first time that there is a Palestinian people. This may sound almost pitiful, but official Israel had rarely, if ever, referred to the Palestinians as a people, so the change of rhetoric was significant, and it had an impact on the public. After the signing of the Declaration of Principles (DOP), official Israeli pronouncements continued to refer to the Palestinian citizens of Israel as “Israeli Arabs,” but the Arabs in the occupied territories were now referred to as “Palestinians.” One might call that progress of some kind.

Amazing Period of Hope and Cooperation

Beyond that, the Accords were initially extremely well received by both publics. Palestinian scouts with their drums took to the streets of East Jerusalem in celebration of the signing on the White House lawn, and Israeli and Palestinian peace activists shared a bottle of champagne at the American Colony Hotel where we watched the signing on a massive screen. An amazing period of hope and cooperation ensued. Contrary to later commentaries claiming that the process was top down and that the populations were not ready for peace, the Oslo period was full of joint activities and enterprises.

Since Peace Now was quite well known, the movement found itself inundated with requests from Palestinians to engage in meetings and dialogue. A group from Gaza initiated a meeting in Kibbutz Nahal Oz to discuss the creation of a joint kindergarten, arguing that we must begin to teach a culture of peace. Former Palestinian prisoners, speaking the Hebrew they had learned in prison, sought out Israeli peace activists to see how we might cooperate. Israelis, too, sought every opportunity to meet with counterparts in the West Bank: architects, archeologists, doctors, teachers and so on. Joint businesses were started, and Israeli-Palestinian women’s groups like the Jerusalem Link grew substantially. One tends to forget the excitement and optimism of those days, despite the often violent opposition of a minority on both sides.

For Israel, the Oslo Accords brought renewed respectability on the international scene, with a virtual doubling of the number of countries with which it had diplomatic relations. Outside investments as well as tourism increased, and contacts, including visits, with Arab states such as Morocco and Tunisia were opened in the form of what diplomacy calls “offices of interest.” The Accords also paved the way to a peace agreement and full diplomatic relations with Jordan; talks with Syria also progressed.

But Israelis were not the only ones to benefit from the Oslo Accords. Despite the problems and the uncertainty, the state of Palestine was now in the making. The establishment of the Palestinian Authority and the Palestinian Legislative Council constituted the beginning of institution-building for the future state. The designing of a constitution, creation and ownership of a Palestinian educational system throughout the occupied territories, a national police force, independent decision-making and open political activity all attested to emerging sovereignty.

Furthermore, the physical return of several thousand Palestinian exiles, including PLO officials and Arafat himself, changed the atmosphere and perspectives of the people in the occupied territories. The assumption and fulfillment of their new responsibilities were not without problems for the Palestinians, but for the most part these were now the problems of a sovereign people governing themselves rather than contending with an outside (Israeli) master. The explicit exclusion of East Jerusalem from the Palestinian Authority was a serious hardship, especially the maintenance of the permit system Israel imposed on Palestinians entering or even traveling within the city, but this did not stop the active involvement of political leaders such as Jerusalemites Faisal Husseini and Sari Nusseibeh or deter cooperation between Israelis and Palestinians in the capital.

Not a Peace Agreement

Palestinians and Israelis alike tended to believe that peace was breaking out, and as a result the violence and the activities of the spoilers were often met with the question: Is this what peace looks like? This very question attests to the mistaken impression held by the two publics. Oslo, after all, was not a peace agreement, and peace had not yet been achieved. The Israeli writer Amos Oz once explained it with the analogy of waking up a patient in the middle of an operation and asking him how he felt! At the same time, because Oslo was not a peace agreement, its ultimate abandonment/failure does not detract from the significance of the breakthrough itself.

Would Oslo have cleared the way for peace — an independent Palestinian state and an end to the conflict — had it survived the terrorism that killed what trust existed between the two peoples and killed Rabin himself? The fact is that we do not know what would have emerged or even what Rabin had in mind. For various reasons — primarily but not only demographic — he wanted to end the occupation (although it took over 10 years for Sharon to be the first Israeli prime minister to utter that word or speak of the need to build a Palestinian state). In his last speech to the Knesset before his assassination, Rabin spoke of “an entity less than a state” and of the need to retain the Jordan Valley (clearly a deal breaker). He may actually have had only some kind of autonomy in mind, such as the autonomy plan he had announced in 1989.

Obviously, the final status of the occupied territories and all the key issues were left to future negotiations. Rabin had believed there were essential psychological issues involved in the conflict and that it would take time to build trust, including a need to test the other side. Oslo was designed to accommodate both these needs, but clearly it had the opposite effect. What little trust existed was whittled away by the actions of the spoilers, and nobody seemed to be passing the “test.”

Yet, this is not to say that Rabin was not genuine or that Oslo was only a plan to benefit Israel. Rabin set timelines for the final status talks, which were to begin no later than three years hence and, most importantly, to end no later than five years from the beginning of Israel’s withdrawals. In Oslo II, Rabin’s last effort to move forward, a schedule was set for the remaining withdrawals, without however, designating the final border. But Oslo was killed along with Rabin. The Likud was never committed to the Accords, and Netanyahu made it quite clear (after Peres’ brief, unsuccessful attempt to carry on) that he had no interest in Oslo or in any further withdrawals or meaningful negotiations.

Still, Oslo succeeded in accomplishing a few things: It put institutions in place on the road to Palestinian statehood; it changed Israeli attitudes toward the Palestinians as a people and a political entity; and it even opened the door to peace by giving birth to the two-state solution as embodied in the mutual recognition — even without official reference to a state at the time. The foundation was laid with the PLO resolution of 1988, but the breakthrough came later with Rabin’s response: the agreement to pursue the Oslo Accords as a move toward a final settlement.