“A picture is worth a thousand words,” said the Chinese philosopher Confucius over 2,500 years ago. That sentence has become a journalistic cliché, even if he was referring to something else. When Confucius said “picture,” he didn’t mean a drawn or photographic image, but rather a direct observation: The picture that is captured by the retina of the eye, the direct observation of an event that has occurred.

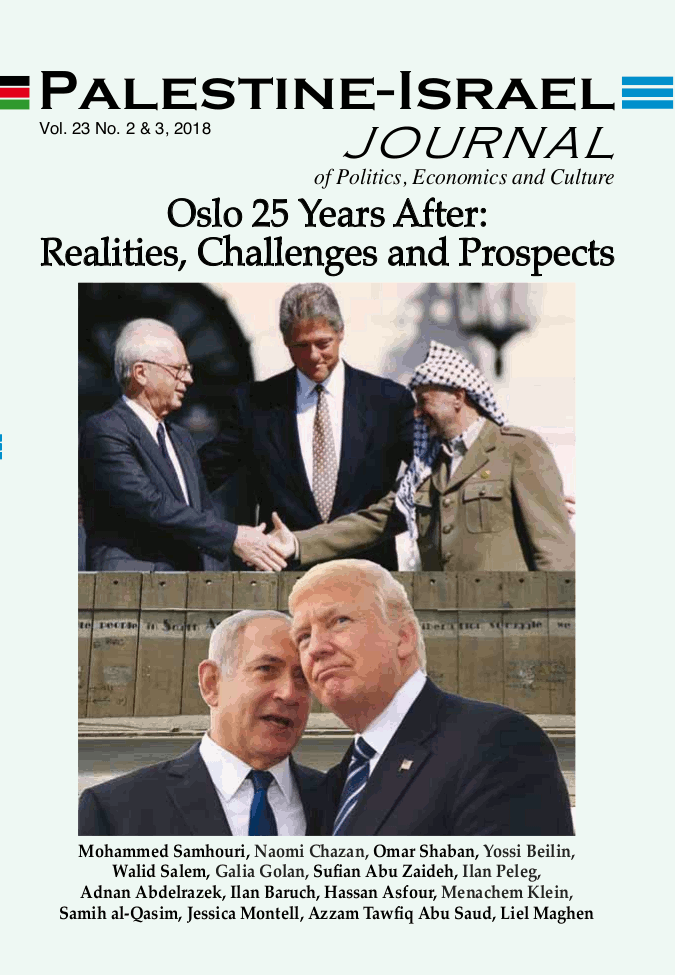

There is no doubt that the picture worth a thousand words from the Oslo Accords is the image of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) Chairman Yasser Arafat shaking hands, with U.S. President Bill Clinton with his arms outspread, hugging the two leaders. The photo was taken on the White House lawn on September 13, 1993, at the festive ceremony of the signing of the “Declaration of Principles on Interim Self-Governing Arrangements,” which were decided upon in Oslo. A deeper examination of the historic photo reveals that the leaders are shaking hands facing each other, but it is not clear if they are looking at each other straight in the eye and with the type of direct observation that Confucius was referring to.

I am trying to recapture how I felt when I saw the image of the three leaders in a live television broadcast from the White House lawn. Already then I felt that there had been greater moments of euphoria in Israeli history. Like most Israelis, I remember being overwhelmed with excitement with our victory at the end of the June 1967 War. The second moment of euphoria was at the time of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat’s visit and his “Peace of the Brave” speech before the Knesset.

The third moment of euphoria, the Oslo Accords was of a lower level, if it is at all possible to measure levels of euphoria. Perhaps the reason for this is that there was a type of sourness in the air because the support for the agreement was not overly impressive. The agreement was ratified in the Knesset with 61 members voting in favor and 50 against, while eight abstained.

Despite that, for me the Oslo Accords were the beginning of a realization of the dream of peace between Israel and the Palestinians which I had been fighting for with the Israeli left for many years.

As a left-wing activist, I joined MK Shulamit Aloni when she left the Labor party and established Ratz, the Movement for Civil Rights and Peace, in 1973, immediately after the Yom Kippur War. To this day I can remember the words that she said after the signing of the Oslo Accords ringing in my ears: “ I feel like its November 29th 1947 all over again (the day the U.N. Partition Plan, General Assembly Resolution 181 was accepted –ed.) —then we didn’t know what we were heading towards, but knew that we were heading towards great days.”

The first part of the agreement was secretly signed in Oslo, the Norwegian capital, on August 20, 1993, by then-Foreign Minister Shimon Peres and Mahmoud Abbas (today the president of the Palestinian Authority). Soon afterwards letters of mutual recognition between the government of Israel and the PLO were exchanged by Rabin and Arafat via Norwegian Foreign Minister Johan Jørgen Holst.

In the letter signed by Rabin, Israel recognized the PLO as the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people, and committed to cancelling the law which forbade meetings with PLO representatives and the declaration that the PLO was a terrorist organization. Arafat in his letter recognized the right of the State of Israel to exist in peace and security, accepted United Nations Security Council Resolutions 242 and 338, pledged to abandon terror and violence and to seek an end to the conflict by peaceful means, and promised to present changes in the Palestinian National Covenant to the articles which reject Israel’s right to exist before the Palestinian National Council.

Various criticisms were heard about the contents, and about the stages and the difficulties in carrying out the agreements, also from leftwing activists and supporters of the agreement, mainly because of the continuation of Palestinian violent activities. Despite this, I felt a sense of hope that was shared by many Israelis, that in the end the agreements would be realized and would lead not only to “arrangements” but at the end of the road to the longed-for peace. Many critics felt that the agreements were flawed from the beginning and at the core because they avoided and postponed seeking solutions for the true problems — the borders and the settlements, Jerusalem, the right of return and more — and left them to the final status agreement.

The Oslo Accords for me and for many other Israeli citizens, Jews and Arabs alike, were the beginning of the realization of a dream. But the watershed moment that broke the dream was the assassination of Rabin. I was one of the 100,000 Israelis in the square that night at the demonstration against violence and for peace. A half an hour before the murder on the steps of the Tel Aviv Municipality, I had passed by the very spot, and that fact only reinforced my feeling of the impact of the murder and its dramatic influence on the continuation of the Oslo Accords.

Although the Oslo Accords were never formally revoked, and parts of them are still being maintained today, most of the stages of its realization are not only not continuing, they are being trampled on by the government of Israel as if they didn’t exist at all.

Between the words “then” and “now” in connection with the Oslo Accords is a line of hope and a line of darkness. However, for me there is nothing more important than grabbing hold of the flickering light that shines at the end of the dark tunnel. That is what gives me and my friends the strength to continue the struggle for the realization of the principles and components of the Oslo Accords, and to realize the goals that we are devoting such an important part of our lives to.