I always knew of Sheikh Jarrah, a Palestinian neighborhood in East Jerusalem, as my father would drive through it, taking a shortcut on the way to the Hebrew University, located on a hillside above it. But we never stopped, as we had no reason to.

There were about 30 of us, Palestinians and Israelis who, one day toward the end of 2008, gathered on a roundabout in the middle of Talbiyeh neighborhood in West Jerusalem, once the home of hundreds of Palestinians who were forbidden from returning to it after the 1948 war. The bored Jewish residents of Talbiyeh looked at us oddly as we erected a tent in the middle of the roundabout.

"What is this?" someone asked.

"We are protesting the eviction of a Palestinian family from Sheikh Jarrah."

"Why here?"

"Because this family, the old woman standing here, was evicted from Sheikh Jarrah on the claim that the land on which she lived belonged to Jews before 1948, so the Palestinian family is here to claim what was theirs before 1948, their house here in Talbiyeh."

The Story of Sheikh JarrahThis is the story of Sheikh Jarrah: 28 families of Palestinian refugees who used to own land in what is now Israel, and were expelled from that land in the 1948 war. Twenty-eight eviction orders from Israeli courts claiming the houses these families now live in were built on land owned by Jews before 1948. Four families were evicted from their houses in the past two years; four settler families moved in in their place. Three protest tents were erected by Palestinians in front of what used to be their homes and were demolished by the Jerusalem municipality; they were re-erected and demolished and re-erected and demolished all over again. One tent still stands. An entire Palestinian community living with daily harassment by settlers and the Israeli police. Twenty-four families living with the knowledge that they could be next.

After two evictions in the summer of 2009 we held a vigil of about 200 people in front of the evicted houses, holding candles, chanting slogans, standing together, the Palestinian residents and the Israeli activists who had come to know the residents personally after spending night after night in houses that were under threat of eviction, hoping to stop it. Nevertheless, all evictions were carried out, and we stood there, helpless.

After the next eviction a few months later, we held a meeting to see what, if anything, could be done. How could we make people listen, force them to know what is going on, a mere 10 minutes from their homes on the other side of the city?

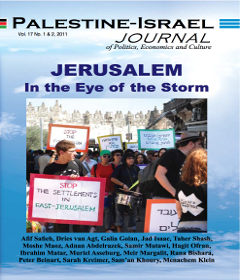

We decided to march every Friday from the bustling, lively city center of West Jerusalem to the depressing reality of Sheikh Jarrah. We made the first march with three drums, 10 signs and barely 30 people. The following week there were 40, and the next 50, and the next 100. We were arrested and dragged out of the neighborhood. The Palestinian activists were interrogated, threatened and arrested randomly. And yet, we kept coming, marching into the neighborhood, making headlines and showing that injustice such as this cannot be ignored and that we cannot be silenced.

Three hundred people now gather every week in Sheikh Jarrah, under the Mediterranean sun or in the rainy Jerusalem winter, chanting to the sound of 20 beating drums: "Free Sheikh Jarrah." Members of the Knesset (the Israeli parliament) have joined; so too have poets, authors, scholars, Palestinians and Israelis as one. In white letters on black T-shirts across our chests is written: "There is nothing holy in an occupied city." Four thousand of us gathered for a mass rally one Saturday night in March. Palestinians from East Jerusalem and from inside Israel, Jews from all over Israel and international activists all stood together. And the Israeli society could no longer ignore it: Something big was happening in Sheikh Jarrah - a great injustice, but also a great and unified call for a nonviolent yet relentless struggle against the occupation.

This Is a Struggle for the FutureI wish I could say that these demonstrations have the power to return the Ghawi family to their home. I wish I could tell the children of the Hannoun family that soon they will be able to return to their old rooms. I wish I could promise the little girl who wondered aloud how a settler can sleep tight in her bed that soon she will be able to sleep again in her bed. But I cannot. This is a struggle for the future. It is about what might happen next.

This struggle might have the capacity to mobilize enough people not to give up a fight before the next eviction, to resist the next eviction, nonviolently but as stubbornly and fearlessly as possible. A hundred of us could get arrested if that new eviction materializes and another family gets evicted in the end, but we will not let it pass silently. We can only hope that the brutal forces in power will take this into account and will desist from attempting another eviction.

It is a struggle not only for the houses in Sheikh Jarrah; it is a part of the anti-occupation movement. It is a young, energetic struggle led by people who have not lost hope and believe that the occupation will end - as it must. It is a joint struggle of Palestinians and Israelis saying that we refuse to be enemies; we refuse to be a part of the separation system forced upon us by the Israeli government; we refuse to play by the unjust laws that are no laws at all.

We still stand in Sheikh Jarrah every week, demanding to enter the neighborhood and to protest against injustice. We are denied entry, and we are detained, beaten and arrested, but still we come again. We stand together on Muslim holidays and Jewish holidays, celebrating together. We stand together in the face of settler and police violence, furious together. We stand in solidarity, fighting injustice, together.