Introduction

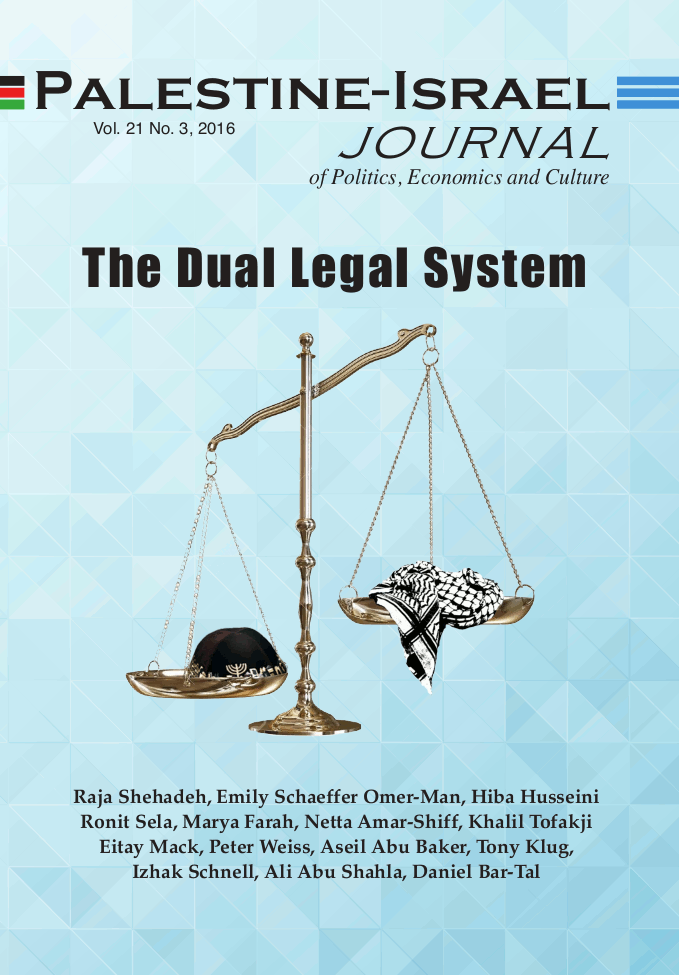

For nearly half a century, Israel has managed to normalize a situation in which criminal law is applied separately and unequally in the West Bank based on nationality alone (Israeli versus Palestinian), inventively weaving its way around the contours of international law in order to preserve and develop its “settlement enterprise.” What is more, while the law is enforced vigorously and aggressively upon Palestinians suspected of crimes against Israelis, Israeli settlers enjoy virtual impunity for acts against Palestinians.

The History of the Application of Law Based on Nationality in the West Bank

Upon Israel's occupation of the West Bank and Gaza (along with the Sinai Peninsula and Golan Heights) in June 1967, the Israeli military immediately established military courts in both territories in order to try offenses harming security and public order.1 These courts were granted broad jurisdiction to try any resident or non-resident of the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT), for any security-related offense committed within or outside the Territories, and other offenses.2 However, as Israeli civilian settlements began to crop up, a problem arose. These courts were designed to try the “enemy” population; where would Israeli citizens in the OPT be tried?

The solution was simple. The Knesset passed a law granting Israeli courts and authorities jurisdiction over any Israeli national accused of committing a crime that violates Israeli law, even if the alleged crime was committed within the OPT.3 The law was passed as an emergency regulation, but it is periodically renewed and in force to this day.4

Technically speaking, Israeli military and civilian courts hold “concurrent” jurisdiction to try Israelis for offenses related to security. The policy for the last four decades, however, has been to refrain from prosecuting Israeli civilians in the military system, despite critiques that doing so constitutes partial annexation of occupied territory.5 Various attempts by Israeli officials to advocate for the exercise of military court jurisdiction over Israeli settlers have been obstructed by the military or political echelons.6

The result is that Israeli and Palestinian neighbors accused of committing the very same crimes in the very same territory are arrested, prosecuted and sentenced in drastically different systems — each featuring staggeringly disparate levels of due process protections.

The Military Courts as Separate and Unequal

International law obligates Israel to maintain basic due process rights when arresting, trying and detaining Palestinians in the OPT. Often referred to as the “right to a fair trial,” those rights include: the presumption of innocence, the right to counsel, the right to be notified of and understand the charges, the right to prepare an effective defense, the right to be tried promptly, the right to interpretation of the proceedings and the right to a public trial.7

However, the Israeli military courts fall short on many of these standards in substantial ways, particularly when compared with the levels of due process protections that the Israeli civilian criminal system affords its nationals when they are suspected of identical crimes.

For instance, while both systems grant arrestees and defendants the right to counsel, only in the Israeli criminal system are indigents regularly provided state-funded public defenders.8 Furthermore, attorney-client meetings prior to interrogation and trial, crucial to protecting the accused's rights and preparing an effective defense, are often delayed significantly, whereas in the Israeli civilian courts, attorney-client meetings are permitted without delay, barring a handful of strict exceptions.9

The right to an effective defense, as well as the accused's right to know and understand the charges, are also hampered in the military courts system, as proceedings are conducted in Hebrew, and all judgments and relevant laws are published in Hebrew only.10 Interpretation during proceedings is provided by Israeli soldiers without legal training and who receive minimal interpretation instruction.11 According to Israeli human rights NGO Yesh Din's monitoring of military courts, interpreters serve several functions simultaneously and interpretation is often incomplete.12

Additionally, while proceedings in Israeli civilian courts are open to the general public with few exceptions, the military courts are located within closed military bases where entry is highly restricted. The above significantly limits the right to a public trial and hinders public scrutiny of the military courts system, which operates in many ways under a veil of darkness.

The Dual Criminal Legal System in Practice

In addition to these structural discrepancies, which have significant bearing on the relative due process protections afforded under each system, the two systems are also distinguished by severe substantive disparities. As such, an Israeli citizen and a Palestinian — both of whom are accused of manslaughter, the Israeli residing in the settlement of Ma’on and the Palestinian in the adjacent village of Al-Tuwani — will be tried before different legal systems. The settler will be processed according to the Israeli Penal Code, which requires he be brought before a judge within 24 hours of arrest, and whose arrest may be extended for a maximum of 30 days. The Palestinian will be processed according to military order, which allows a suspect to be detained for up to four days after arrest before being brought before a judge, followed by 30-day extensions for up to three months. They will be tried before different courts: the Israeli by fellow Israeli judges and prosecutors; the Palestinian by uniformed prosecutors and judges, commissioned by the occupying army. If convicted of manslaughter, the Israeli may be sentenced to up to 20 years’ imprisonment; the Palestinian may be sentenced to up to life imprisonment.

Virtual Impunity for One Population: Settlers Who Commit Crimes against Palestinians and Their Property

Ideologically motivated crimes by settlers against Palestinians, what have been dubbed “settler violence,” “Jewish terror” or “price-tag attacks,” occur on a regular basis across the West Bank, particularly in areas of high friction where settlers and Palestinians live side-by-side. The types of crimes committed against Palestinians and their property include: violent crimes, from shooting, beatings, stone throwing and various armed assaults; property damage, such as arson and vandalism of homes and crops; theft of trees and livestock; attempts to seize control of privately-owned land by means such as trespassing, waste-dumping, fencing off, cultivating, erecting structures and other means of driving Palestinians off their plots or otherwise denying them access thereto.13

As discussed above, the Israel police and the Israeli criminal system are charged with investigating and prosecuting crimes by settlers against Palestinians. In order to file criminal complaints against settlers, Palestinians must reach Israeli police stations, primarily located in settlements across the West Bank, to which Palestinians are generally barred access without a police escort. This situation, along with remarkably low rates of prosecution, deters many Palestinians from filing complaints against Israeli citizens in the first place.

According to data collected by Yesh Din, of more than 1,200 cases of ideologically motivated settler crimes against Palestinians tracked by the organization between 2005 and 2015, 91.6% were closed without indictment.14 Among these cases, some 85% were closed on grounds indicating police negligence and deficiencies, from not examining the crime scene and collecting pertinent evidence, to failing to identify and interrogate key witnesses or verify alibis.15 In the rare cases when Israelis are indicted for crimes against Palestinians, only one-third of legal proceedings lead to full or partial conviction and the sentences are relatively lenient.16 Given this state of affairs, the chances that a Palestinian complaint to the Israel police will result in an effective investigation, prosecution and conviction is just 1.9 percent.17

What is more, the lack of adequate law enforcement creates a culture of impunity and emboldens settlers to continue to perpetrate these acts. The situation is exacerbated by the fact that Israeli soldiers, who often lack instruction on their duty to protect Palestinians and detain Israelis caught in the act, regularly stand idly by while settlers continue to attack Palestinians and their property.18 Since August 2014, the incidence of ideologically motivated crime perpetrated within Palestinian residential areas, as opposed to agricultural areas, has doubled.19 As settler violence intensifies, studies show that Palestinians increasingly abandon their land out of fear of retaliation, creating “no-go zones.”20

Conclusion

Israel is under strict obligation to protect Palestinians and their property from harm and to uphold their basic due process rights. Instead, it has established and maintained for nearly a half-century a dual criminal system under which the West Bank Palestinian population is unequal under the law, while the settler population is granted virtual carte blanche to carry out acts that directly translate into dispossessing Palestinians of their land, making way for the constant expansion of the settlement enterprise.

Endnotes

1 Under international humanitarian law, the body of international law dealing with war and occupation, an occupying power has the authority to establish “properly constituted, non-political military courts” to try residents of the occupied territory for offenses harming security and public order. See specifically, Articles 66, et. al. of the Fourth Geneva Convention Relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War (1949) [hereinafter: “the Fourth Geneva Convention”]. Today military courts serve only the West Bank, located in Ofer and Salem.

2Sec. 7 of the Order Concerning Security Provisions (Judea and Samaria) (No. 378), 5272-1967. It should be noted that offenses over which the military courts hold jurisdiction are not limited to offenses against security and public order and thus represent an expansion of the authority granted by the Fourth Geneva Convention.

3Amendment and Extension of the State of Emergency Regulations (Judea and Samaria – Jurisdiction over Offenses and Legal Assistance), 1967. See also ACRI, ONE RULE, TWO LEGAL SYSTEMS: ISRAEL'S REGIME OF LAWS IN THE WEST BANK (October 2014), at 15-18.

4The law was most recently extended in 2012 through June 2017.

5Application of Israeli domestic law in the Occupied Territories is a violation of international law as it constitutes prohibited annexation of occupied territory. See, e.g., Article 42 of the Regulations annexed to the Hague Convention (IV) Respecting the Laws and Customs of War on Land (1907); Article 43 of the Fourth Geneva Convention. In order to avoid annexation, criminal law alone is applied personally and extraterritorially to Israelis in the West Bank, rather than wholesale application of Israeli law over the territory and all its residents (as is the case in East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights).

6A handful of Israeli demonstrators were prosecuted in the military courts in the 1970s and early 1980s, but not since. See, e.g. Gideon Alon, Libai, Shahal and Brig. Gen. Schiff Reject Ben-Yair's Proposal to Transfer the Handling of Settlers to Military Courts, Haaretz, May 3, 1995 [Hebrew]; Tal Rozner, Settler, Go to the Guardhouse, YNET, Jan. 14, 2005 [Hebrew].

7See Articles 9 and 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) of 1966; Articles 71, 72 and 74 of the Fourth Geneva Convention; General Comment 13, the United Nations Human Rights Committee. The Israeli Government denies the applicability of international human rights legal instruments (such as the ICCPR) in the occupied territories; however, the Israeli Supreme Court has repeatedly deferred to international human rights law “for the sake of argument”, and the highest international judicial body, the International Court of Justice, has ruled in two of its Advisory Opinions that international human rights law applies in an occupation and fills in the gaps in international humanitarian law. See, e.g. ICJ, Advisory Opinion, Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (July 4, 2009).

8See Sec. 18, Public Defender Law, 1995, for a list of arrestees and defendants eligible for public defense, including cases in which the prosecution has requested a prison sentence, minors and disabled persons. In the military courts, in contravention of international law, only those accused of crimes bearing 10-year prison sentences must be appointed counsel if they are unrepresented. In practice, the system relies on the several Palestinian organizations that provide free legal assistance to military court arrestees and defendants and supersede the need for court-appointed counsel. While judges are often reluctant to allow trials of major offenses to proceed without representation once reaching the evidentiary stage, lesser offenses are regularly adjudicated in the military courts without the assistance of legal counsel. See Yesh Din report, BACKYARD PROCEEDINGS: THE IMPLEMENTATION OF DUE PROCESS RIGHTS IN THE MILITARY COURTS IN THE OCCUPIED TERRITORIES (December 2007) at 21 (available at www.yesh-din.org) [hereinafter “Backyard Proceedings”] at 101-107.

9Attorney-client meetings in the military courts system may be barred for up to 30 days. When the defense attorney is a Palestinian resident of the West Bank, additional restrictions on freedom of movement may also come into play, particularly where Palestinians are held inside Israel in contravention of international law (Article 76 of the Fourth Geneva Convention). It should be noted that in the Israeli criminal system certain cases are classified as “security violations,” and in such cases, for instance, attorney-client meetings may be delayed up to 6 days and extended up to 21 days with special approval. However, Israeli violence against Palestinians in the West Bank is not typically classified as a security violation.

10As of late November 2012, indictment sheets are translated into Arabic, but all decisions, verdicts, court transcripts and laws are published in Hebrew only. See Israeli Supreme Court decision in HCJ 2775/11, Atty. Khaled Al-Arj et. al. v. IDF Commander, et. al. (Feb. 3, 2013).

11See, e.g. Yesh Din report, BACKYARD PROCEEDINGS at 20-21. For more on military court interpreters, see Lisa Hajarr, COURTING CONFLICT: THE ISRAELI MILITARY COURT SYSTEM IN THE WEST BANK AND GAZA (2005), at 132-153.

12Yesh Din report, BACKYARD PROCEEDINGS at 21.

13Violent crimes represent over a third of crimes committed against Palestinians over the last decade, and property damage constitutes nearly half. See e.g., Yesh Din Data Sheet October 2015, LAW ENFORCEMENT ON ISRAELI CIVILIANS IN THE WEST BANK: YESH DIN MONITORING UPDATE 2005-2015 (available at www.yesh-din.org).

14Id. at 2. It should also be noted that while overall rates of indictment in the Israeli court system are similar (approximately 10% as of 2011), Yesh Din's figures relate to ideologically motivated crimes only, and thus the comparison is misleading. Ideologically motivated crime is equated to security crime, or terror in certain instances, and thus law enforcement agencies invest additional resources in investigating these cases within Israel. It is reasonable to assume that the national rate of indictment for ideologically motivated offenses is significantly higher than the general figure and, accordingly, the rates of indictment of Israelis in the West Bank for these crimes is incomparably low. (2011 figure from Yaron Doron, “Fall in Number of Police Cases Resolved,” Yediot Acharonot, February 8, 2012 (Hebrew).

15For more details on the extent and nature of the Israel Police's failure to adequately investigate these crimes, see Yesh Din report: MOCK ENFORCEMENT: THE FAILURE TO ENFORCE THE LAW ON ISRAELI CIVILIANS IN THE WEST BANK (May 2015) (available at www. yesh-din.org) [hereinafter: “Mock Enforcement”].

16Similar to the comparison of rates of indictment in footnote 14 above, while overall conviction rates in the two systems are similar (around 99% in the military courts and between 97-99% in Israeli civilian courts), a comparison of convictions for crimes committed by Israelis against Palestinians in the West Bank to the reverse, the disparity is stark: one-third versus 99%, respectively. See Yesh Din Datasheet, PROSECUTION OF ISRAELI CIVILIANS SUSPECTED OF HARMING PALESTINIANS IN THE WEST BANK (May 2015) (available at www.yesh-din.org).

17Id.

18See Yesh Din Report, STANDING IDLY BY: IDF SOLDIERS’ INACTION IN THE FACE OF OFFENSES PERPETRATED BY ISRAELIS AGAINST PALESTINIANS IN THE WEST BANK (May 2015) (available at www.yesh-din.org).

19Yesh Din, MOCK ENFORCEMENT at 1.

20See Yesh Din Report documenting the phenomenon, THE ROAD TO DISPOSSESSION (February 2013) (available at www.yesh-din.org).