Over the last 18 years or so, and especially since the crushing collapse of the Camp David II negotiations (2000), it has become fashionable among politicians, policymakers and academics to declare the death of the two-state solution in general and the demise of the Oslo Accords in particular. Now, on the eve of the 25th anniversary of the September 13, 1993 signing of Oslo (formally known as the Declaration of Principles) by representatives of the State of Israel and the leadership of the Palestine Liberation Organization, it might be useful to assess Oslo in a broader manner in order to formulate a balanced view of that important event and soberly evaluate its impact on the future of Israeli-Palestinian relations. I would like to suggest that the bottom line of such a re-examination of Oslo might be formulated in an inherently contradictory statement: “While Oslo as a specific diplomatic process may have died, Oslo as a fundamental principled idea is very much alive.”

The Oslo Accords were highly controversial from the start, and predictably so. They tried to move the ball forward on what has been the single most politically complex and emotionally ridden conflict in the world since the end of World War II. That complexity and emotionality were rooted in the ever-escalating dispute between two national movements — the Jewish/Zionist and the Palestinian/Arab — over territory situated in an area (the Greater Middle East) already plagued by great instability. The conflict has been negatively influenced by excessive religiosity on both sides, images of colonialism and exploitation, and an internalized sense of national victimhood rooted in such monumentally painful events as the Shoah and the Nakba.

Despite the depth of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the Oslo Accords tried to create a framework for a peaceful settlement negotiated by the warring parties with the active support of outside powers, however big (the United States) or small (Norway). While Oslo did not mention explicitly the establishment of a Palestinian state, it clearly recognized the PLO as the representative of the Palestinian people. Since distinct people are often entitled to a state of their own in accordance with the fundamental idea of “self-determination” and international law in general, given that the Occupied Palestinian Territories are demographically Palestinian and in view of Jordan’s withdrawal from the West Bank, it could be convincingly argued that Oslo endorsed, albeit implicitly, the eventual establishment of a Palestinian state in the Palestinian territories occupied by Israel during the 1967 war.

Unfortunately, Oslo failed, at least in the short term and as seen from the historical perspective of the agreement’s 25th anniversary. In the long run, however, Oslo and the two-state solution implied by it may still prove successful despite their faults and given the immense problems with agreeing on and implementing any imaginable alternative solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Negating Oslo

Several major arguments about the negativity of Oslo and the twostate solution that is implicitly connected to it have been raised since 1993:

- 1. Oslo reflected the capitulation of the PLO or, as Edward Said called it, “the Palestinian Versailles,” the argument being that by signing Oslo the Palestinians gave up their claim to the entire West Bank and Gaza;

- 2. Oslo could turn the interim arrangement — the establishment of Palestinian self-government in the Occupied Territories — into the ultimate result of the negotiations. That is, Oslo might derail progress toward the establishment of a fully independent Palestinian state;

- 3. Oslo relegated the Diaspora Palestinians, as distinguished from West Bankers and Gazans, to permanent refugee status, ignoring their Right of Return (presumably to their homes in Palestine or Israel);

- 4. The failure of Oslo and the Two-State Solution to produce significant progress toward a negotiated settlement has proven that these solutions to the conflict are complete illusions;

- 5. Oslo supporters of all types have backed the Accords for selfish reasons: the Palestinian Authority to keep power, the Israeli government to avoid international pressure, U.S. politicians to demonstrate commitment to a solution, and so forth.

- 6. Oslo and the Two-State Solution have become an industry for diplomats, advisers, experts, academics, and journalists but, given the positions of the parties, the chances for an actual peace agreement based on a negotiated two-state solution are low (some say, nonexistent).

- 7. The Oslo two-state “process,” while officially supported by the United States, is, in fact, being destroyed by the unconditional American support of Israel as it undermines Israel’s interest in compromising;

- 8. The almost universal support for the two-state solution takes all the attention away from other alternative solutions, some of them with real potential for success.

Reaffirming Oslo

While these and other anti-Oslo arguments in their totality are quite impressive, they must be balanced with a set of arguments that support the legacy of Oslo and emphasize the preferred viability of the two-state solution, especially when compared with any other alternative solution:

- 1. Oslo was the first time that the representatives of the Jewish national movement (the Israeli government) and the indigenous Palestinian population (the PLO) publicly and officially recognized each other, thereby breaking a long-standing historical taboo.

- 2. Oslo created a new reality on the ground in which Palestinians were given, for the first time ever, a measure of self-government, at least some control over their affairs, and the ability to select their own leadership.

- 3. While Oslo has not resulted in Palestinian sovereignty, it led to a series of negotiations and agreements between Israel and Palestinian representatives, thereby establishing and strengthening the idea and the reality of a Palestinian nation, an entity that is now widely recognized internationally.

- 4. Oslo was accompanied by several large-scale mistakes, but these do not mean that Oslo and the two-state solution are fundamentally erroneous. For example, although Oslo did not include a freeze on settlement activities in the West Bank and Gaza and projected a long process of negotiations and then implementation, thereby enabling opponents to derail the entire process, these serious tactical errors do not negate the Oslo principles.

- 5. The implementation of Oslo has been faulty, designed to fail. For example, there has been an assumption that the way toward a negotiated settlement must be exclusively through direct negotiations between the parties, a provision giving each party veto power over progress and granting the upper hand to the stronger party, Israel.

Thinking Beyond Oslo

While the so-called “Oslo peace process” and the pursuit of the Two- State Solution have emerged as somewhat of a cottage industry, challenging Oslo and the Two-State Solution has also become the favorite subject of numerous politicians, commentators, and analysts, particularly over the last decade or so. Attacks on Oslo have come from both the right, often by annexationists who believe in formally incorporating the Occupied Territories into Israel, and from the left, by people supporting some variation of the so-called one-state Solution. More recently, as both two-statists and one-statists have been unable to convincingly defend their position and as the reality on the ground in Palestine/Israel has become grimmer and grimmer in terms of finding any negotiated, agreed-upon solution, analysts have begun to increasingly recommend confederal solutions.

In thinking about moving beyond Oslo after 25 years of accumulated frustrations — by possibly building on some of the (mostly) strategic principles of Oslo while learning from some of the (mostly) tactical mistakes made in trying to implement the Accords — it might be useful to think about alternative constitutional orders for the Israel/Palestine problem and identify some of their advantages and disadvantages. Following is an examination of the six theoretically possible solutions to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict from an Oslo perspective.

- 1. The Oslo Accords seem to have assumed the evolution of the interim agreement into an eventual two-state Solution based on the territorial division of the land. While Oslo never stated this goal in so many words (a strategic mistake of the first order in and of itself), in recognizing the PLO as the representative of the Palestinian people and allowing it to establish a territorial base in some of the Palestinian-inhabited areas of the land, no other alternative seems likely or even possible.

- 2. A second solution, much less compatible with the logic of Oslo, is the establishment of a Bi-national Democratic State in which Palestinian Arabs and Israeli Jews, recognized as national collectivities (like Catholics & Protestants in Northern Ireland,) share power in a newly established Israeli-Palestinian state. So far, no one has been able to offer a convincing design for such a state, and it is clearly against the wishes of the vast majority of Israeli Jews who insist on Israel remaining a Jewish State.

- 3. A third possibility for the future of Israel/Palestine is the creation of a true liberal democracy based on “Western” principles, a Unitary Democratic State in which all citizens enjoy equal rights as individuals and no group rights are given. In terms of demographics, the number of Jews and Arabs in such a state would be even, and with time the Arabs could gain the demographic upper hand. Again, there is no reason to believe that the majority of Israeli Jews will accept such a solution.

- 4. A fourth solution is the incorporation of all or most of the Occupied Territories into Israel via a formal act of annexation, a solution recommended by radical Israeli right-wingers. Such a solution would totally negate the Oslo Accords in letter and spirit and is likely to escalate the Israeli-Palestinian conflict to unprecedented levels.

- 5. A fifth solution is to maintain the status quo (that is, sustain the Israeli occupation) as established after the 1967 war. This “solution” clearly violates the Oslo rationale that viewed the situation as unsustainable and greatly undesirable. Moreover, by its very nature, such a solution (or, essentially, non-solution) aggravates all the problems that led to the Oslo Accords in the first place, including the strengthening of radical, nationalist, and religious fundamentalist forces on both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian divide.

- 6. A sixth solution which constitutes an attempt to circumvent the pitfalls of all the other solutions, especially the one-state and two-state solutions, and rejects the possibility of either binationalism or liberal democracy as well as the desirability of the status quo, is the establishment of a confederal state. The modalities of such a solution would need to be fleshed out in a lot more detail before it could be seriously adopted, but confederation of any type would require the type of cooperation and compromising proclivity that the parties to this conflict have never shown.

Oslo as a Process Versus Oslo as an Idea

Whatever solution is finally pursued or adopted to resolve the Israeli- Palestinian conflict, the “Oslo experience” ought to be studied carefully in order to avoid some past mistakes while, at the same time, incorporating positive lessons into whatever new designs are promoted.

In assessing Oslo 25 years later, it is crucial to look at it in two diametrically opposed ways:

- 1. First, we need to look at Oslo as a process. Oslo was designed to bring about a resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict through negotiations about a two-state solution, probably with active U.S. mediation and legitimizing international endorsement. This particular process died years ago, particularly as a result of violent actions by people on both sides (such as Dr. Baruch Goldstein, Yigal Amir and Islamic suicide bombers) as well as active opposition to Oslo on the part of prominent Israeli and Palestinian political figures.

- 2. Second, as an idea, Oslo is very much alive even today, more than 20 years after its premature death as a particular political process. Oslo was based on the idea that there are two distinct nations in the land known as “Palestine” or “Eretz Yisrael” (an idea recognized already by the 1937 Peel Report and later endorsed internationally in the UN Partition Resolution) and that both of these nations deserve official and public recognition leading, in all likelihood, to their distinct sovereignty in part of the land. While many of the parameters of the future sovereignty were left undefined by Oslo (a significant tactical mistake by the negotiators,) including the precise lines delineating the borders between the states, the notion of dividing the territory into two sovereign states was quite clear to the Oslo negotiators.

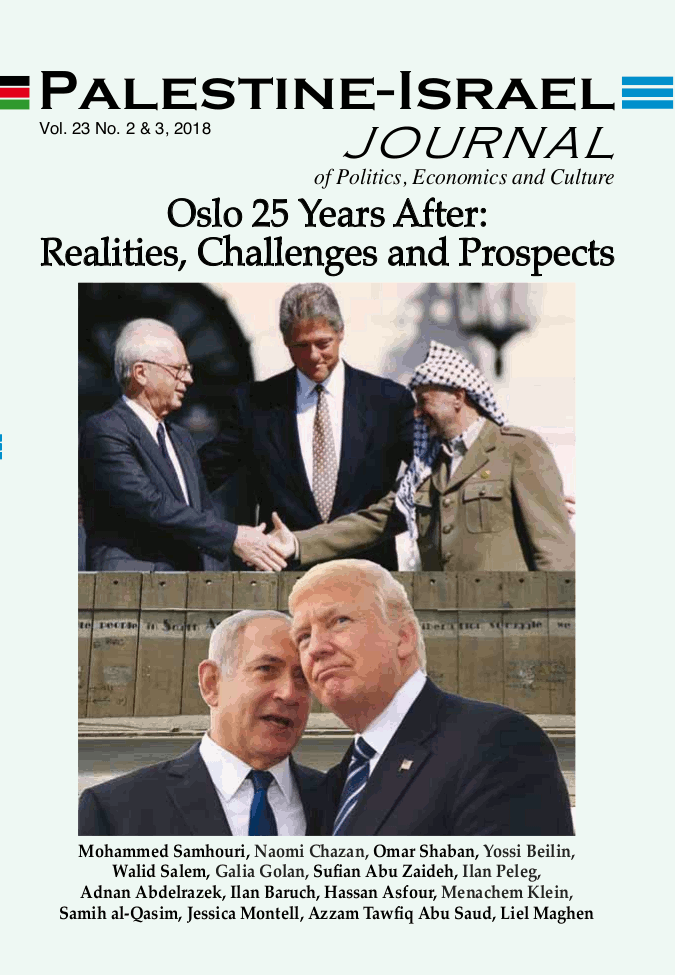

The Netanyahu Factor: The Victory of Nationalism

The fate of the Oslo Accords cannot be separated from at least two connected, large-scale historical phenomena. The first is the rise to power of Benjamin Netanyahu in 1996 and his return to power in 2009, and the second is the overall emergence of a nationalist, right-leaning regime in Israel, a phenomenon that preceded Netanyahu but has greatly intensified and gained legitimacy under his regime.

Immediately following the announcement of an emerging Israeli-Palestinian “deal” — later becoming the Declaration of Principles or simply “Oslo” — Benjamin Netanyahu, then the newly elected leader of the Likud, expressed his total, unrestrained opposition to the agreement. In the strongest possible way, he compared it to the Munich Agreement of 1938, an agreement that led eventually to World War II and sealed the fate of European Jewry. With Netanyahu’s surprising emergence as Israel’s Prime Minister, Oslo was put on life support, formally allowed to exist but politically dead.

Looking at Oslo from the perspective of its 25th anniversary, it is quite clear that the obliteration of the Oslo vision has become Netanyahu’s ideological life-project and that, at least as of now, he has done a good job of damaging, if not utterly destroying, it.

But to understand Bibi’s policy toward Oslo and his commitment to obliterate it, albeit without ever formally abrogating it, one has to understand right-wing Zionist ideology in the broader context. It has always been an ideology based on the assumption that Jews have exclusive rights over Eretz Yisrael. Oslo not only challenged this assumption theoretically but rejected it practically.

In laying the foundation for Oslo, Yitzhak Rabin said to the Knesset during the introduction of his government in July 1992: It is about time that we cease arguing that the entire world is against us (HaOlam kulo negdeinu). In other words, Rabin tried to convince Israelis to adopt an alternative view to the one dominating Israeli public discourse for decades, particularly under the Likud government. In the final analysis, Oslo was an attempt to implement the alternative position, but in this it failed.

Victor Hugo said that nothing is more powerful than an idea whose time has come. The idea of establishing two distinct national sovereign states in Palestine/Israel certainly dominated the Oslo negotiations, but one could argue that the time of that idea had not yet come in the mid-1990s and perhaps not even in 2018 and beyond, although counter-arguments are very much preferred by this author.

The arguments against Oslo gain strength if one views both Israeli and Palestinian nationalisms as too inflexible, confrontational and exclusive to compromise with their perceived opponents in pursuit of an equitable political solution. Yet the fact is that Israel is immeasurably more powerful than the Palestinians and therefore holds the key to the territorial solution envisioned by the Oslo negotiators. When one considers that the most prominent political actor promoting the anti-Oslo position since 1993 has been Netanyahu, his longevity as Israel’s prime minister suggests that the future of the “Oslo vision” may be grim.