The position presented in this article is based on the belief that most women in Israel, regardless of their ethnicity, education level, or political agenda, strive to live in peace. Although most of them may believe it impossible and many may believe that they cannot promote peace in any way, as studies of global peace processes and agreements suggest, peace requires wide public support from across as many sectors as possible.

Reviewing the history of peace movements in Israel, we can see that women have always played an active role in peace organizations, NGOs, and initiatives. Yet, despite their significant presence in terms of numbers, they remain severely underrepresented in decision-making processes, whether organizational or national.

The sense of exclusion from decision-making processes and marginalization in mixed-gender peace organizations is felt even by women in senior military or academic positions. Yael, a former senior official in the Israel Defense Force and the Israeli security establishment, described her experience in a mixed-gender peace organization of retired officers: “They realized it was not politically correct to have no women at all. They realized it didn’t look good, so they decided to add some women, but only for the sake of appearances.”

Reasons for the Marginalization of Israeli Women

The marginalization of Israeli women in decision-making processes can be explained by various factors, based on past and current Israeli realities: militarism, the Zionist ethos, mandatory male and female military service “the people’s army”, the Jewish people’s history of persecution, religious influences, attitudes toward minorities and foreigners, social schisms, the neo-liberal economy, and more. Up until the Oslo Accords (1993), peace movements in general, were not recognized or included in Israeli peace negotiations. Even in the Oslo Accords, which were preceded by Track II negotiations in which Israeli and Palestinian women played a significant role, their contribution went unrecognized.

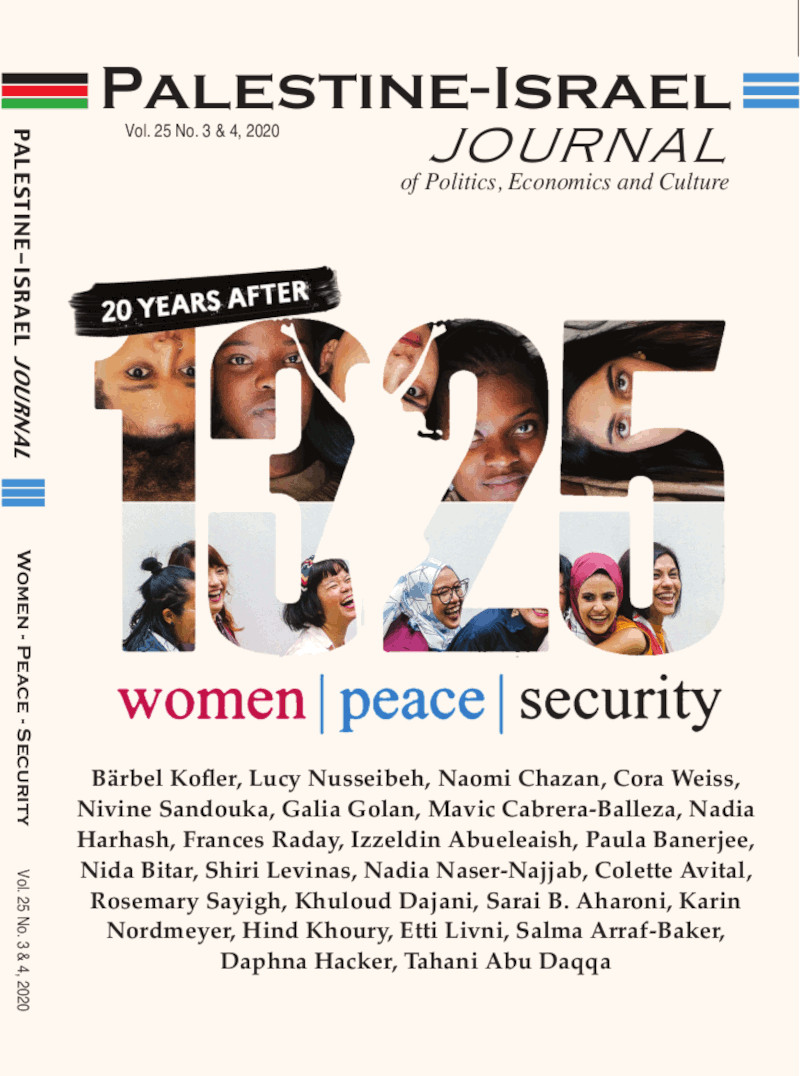

Additional barriers stem from hidden aspects in the operational mode of peace movements, largely related to issues like diversity, belonging, and participation. These issues are at the core of feminist peace activists’ criticism concerning the implementation of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325. A key argument in this regard is that despite the resolution’s important contribution in incorporating gender perspective into peace and security processes, it (and the other nine resolutions that came after it) avoided issues of diversity, belonging, and the participation of women from diverse social groups in these processes. Feminist activists and

scholars in Israel and in the world presented a solution for these lacunas by incorporating the theory of intersectionality with the resolution’s principles. This combination enables the exploration of women’s life experiences based on social intersectionality like class, nationality and ethnicity, and their power relations. Hence, it allows us to reveal how the perception of women as a single category leads to a failure in understanding the structures of inequality between women and among social groups in a conflict. In

addition, the incorporation of intersectionality expands and alternates the meaning of concepts like “peace” and “security,” allowing us to explore their subjective meanings for different women. This academic process established the connection between feminist and peace issues, while also exposing gaps and disputes between different social groups. One example is the decision by a group of Palestinian Israeli women to stop participating in the National Action Plan following a dispute concerning the issue of the occupation and its position in the plan’s agenda.

Collective Identities Affect Access to Civil Rights

The accessibility of civil rights for Israeli women differs based on social class and other collective identities like nationality (Arab/Jew), religiosity (religious/secular), sexual identity (LGBT), or ethnicity (Mizrahi/Ashkenazi). Peace organizations are traditionally more accessible for Ashkenazi, educated, middle-class women.

Debby Lerman, a former activist in the Coalition of Women for Peace, was interviewed by Hedva Isachar in her book Sisters in Peace, which looked at women’s activity in peace and left-wing organizations: “We also failed because we were unable to leave behind our very specific definition: Petit bourgeois, Ashkenazi women, most of us from urban areas (there are some women from kibbutzim, but no one from moshavim or peripheral towns) ... and we weren’t able to expand” (p. 73). The absence of Arab, poor, Russian, Ethiopian, blue-collar, religious, and other types of women stands out and, in turn, encourages some of these organizations to make an effort to expand their target audience.

A Need for Greater Diversity

To try to change the share of participation of women from diverse social groups (particularly Arab, Mizrahi, Russian, and young women), several organizations offered salaried jobs with different projects. This way, the organizations were hoping to create diversity and open the door for additional women to join their activity. Orna, a Mizrahi social activist who was employed by a peace organization, summarized her experience as a project manager: “We failed to deliver.” Other interviewees expressed similar feelings. It seems that the women were perceived by the organizations as representatives of their communities, expecting them to attract a greater audience of women, which created a sense of exclusion and disappointment among many of them. The organizational expectation of women to serve as “recruiters” was extended to volunteers as well. Sentences like “I want you to get a crowd,” “How many did you bring with you?” “Where are her women?” were directed to diverse activists, while the “natural” activists were not subjected to the same expectations.

The desire to increase diversity often leads to misrepresentation, where the few diverse representatives are used by the organization as “presenters.” Sapir Slutzker Amran, a Mizrahi social activist, said in an interview in the Haaretz newspaper: “The Mizrahi women activists were expected to bring more women to demonstrations, for color’s sake, but they were excluded from decision-making processes.” She believes this is the reason that to this day, Mizrahi women are still a minority in feminist or human right organizations. A similar feeling was expressed in an interview with Yuval, from Ofakim (a development town in the Israeli social and geographic periphery), who had been active in the Women Wage Peace movement and said she felt like a “poster girl” for the movement.

The lack of diversity may also be dictated by gatekeepers, who implement a scale that measures the level of compatibility of women wishing to take part in the activity against their suggested activities. One of the criteria set by peace movement activists is self-definition as a feminist. Yet, studies and field reports suggest that peace movements that do not set this criterion often serve as a “gender school,” a sphere for the development of feminist identity. Thus, the self-definition sphere in organizations that do not set feminism as a prerequisite allows many women to gradually define themselves as feminists. They were not required to be feminists to become activists; rather, their activism brought about the potential of choosing to become a feminist.

Another common prerequisite among Israeli peace activists is being part of the Israeli political left. Merav, a young Jewish woman from the settlement of Efrat, described in an interview how, through her involvement in the peace movement, she realized how “our reality is related to the military regime ... and its implications for the Palestinian population.” The call to eliminate the prerequisite of being part of the political left and resisting the occupation does not suggest lack of support or belief in the importance of organizations and activities that actively fight the occupation; it suggests that by integrating women from the Israeli political right in peace-supporting activity, we may be able to expand the circles of peace supporters in Israeli society.

The diversity challenge is complicated and requires commitment, an awareness of privileges and power positions, a willingness to pay prices, and a continuous effort. The diversity slogan can become a reality through a number of relevant paths: Diversity should be reflected in roles, representation, decision-making processes, and resource accessibility (like media and conference appearances, connections with international and local entities, salaried jobs, physical accessibility, etc.), recognizing the differences between women and their different contributions. The ideal way to create diversity is to bring together different types of women as early as the establishment of the movement, allowing these women to take an equal and active role in the definition of the change theory, target audiences, goals, and vision. This description is somewhat utopian, however, as many movements are already established and active, and a new movement, if established in the future, would probably be launched by women who know each other.

The Privileges Discourse

Hence, the first step in changing an existing organization is to recognize the privileges of the movement’s activists. The privileges discourse is often resisted, particularly among social activists, who dedicate their time and energy for the greater good. Most of us find it difficult to distinguish between hardships experienced in our lives and privileges offered to us based on our belonging to a specific social group. Thus, for example, in workshops dedicated to this issue, many activist women interpreted the question about privileges as meaning that their struggles, hardships, and efforts are unimportant compared with those of underprivileged groups. Furthermore, the mere question “Is the option of volunteering in a peace movement an expression of privilege?” raised a lot of confusion and discomfort.

The privileges discourse should not be comfortable. In fact, the discomfort triggered by this discourse can be used to expand awareness of inequalities. The recognition of privilege allows us to approach or connect with new audiences, while challenging our previous basic assumptions (in terms of activities’ accessibility, hours, transportation, costs, language, and more).

Is Being a Feminist a Prerequisite for Being a Peace Activist?

Another barrier is the common perception in Israel rendering women’s opinions about peace and security issues irrelevant. This barrier includes an additional significant layer — the fact that many women perceive themselves as “irrelevant.” “This is just my opinion,” “Why me?” “I don’t know enough about it,” and other statements in the same spirit are often expressed by women activists regardless of their status, experience, and expertise when asked to talk about themselves, appear before a public or in the media, or

represent their organization.

To overcome this barrier, peace organizations (whether led by women or mixed-gender) should create safe learning spheres in relevant issues, like different models of women peace activists, the history of women in peace movements, Resolution 1325, feminist theories, and different aspects of the conflict, allowing them to experiment and find their independent voice and position. Women should be exposed to experts in the field, so they can later express their knowledge in their own voice and language. They should be trained in conflict transformation and handling opposition. This is a crucial skill for peace activists, but most of the women in these

organizations lack the knowledge and experience required. Nurturing female activists is powerful leverage and a tool that can help create commitment and expand diversity.

The Violence Barrier

Violence against peace activists is another significant barrier. Many female peace activists are labeled as “enemies of the people” in Israeli society.

Peace activists in Israel are exposed to various types of violence, which can be physical or verbal and take the form of exclusion from different social circles or threats to their families. Dealing with these types of violence is not an easy task. Women who are exposed to them are affected mentally and physically and are sometimes deterred from participating in further activities. In 2017, a couple of Israeli women’s organizations (the Coalition of Women for Peace and Women’s Security Index) published a report about the security and insecurity of activists from a feminist point of view, which analyzed instances of civil or military violence and detailed the fears and concerns of women activists. Half of the participants in the survey said that their activity level is not as high as they would like it to be, because they are concerned about their safety. The differences between types and scopes of violence are often related to the social positions and identities of the women activists. An activist of Ethiopian origin was quoted in the report as saying:

I encounter harsh violence, particularly in my activity against racism toward Ethiopians. I am an Ethiopian woman,

therefore I experience a lot of racism that includes sexual assault and physical violence, and humiliating treatment

while stating the fact that my skin color is the motive. Official forces arresting me often use vile names like “a piece of shit,” (p.3).

The efforts and ambition to create partnerships with diverse women should take into account the different tolls taken by different population groups. We must tread carefully when “pushing” an activist to take an active part in the organization to avoid collision with their community norms. We must be aware of their experiences and provide protection and solidarity as needed. To understand the different types and effects of violence on different women, we must maintain open channels of sharing, consultation, and help.

It is critically important that we discuss the barriers preventing women from participating in peace movements, as this reflective process enables us to identify alternative paths and additional spheres of impact. Equally important, identifying the hidden barriers at the core of the organizational activity may open new opportunities for women activists, allowing them to change their status without waiting for the establishment’s recognition or invitation.

Resolution 1325 Is an Opportunity

Despite the many barriers encountered by women activists in Israeli peace movements, they have managed and still manage to make a change in the conflicted Israeli reality. Their intensive and determined activity helps us expand our interpretation of the terms “peace” and “security,” thus, creating a deeper understanding of the conflict and its implication for the Israeli population, connecting women’s personal insecurity to the lack of national security, and inspiring women around the world. (One prime example is Women in Black, which became an international movement still active today; another is the selection of Women Wage Peace as a special advisor to the United Nations.)

Resolution 1325 supports women’s activism for peace, helping, among other things, in promoting the demand to integrate women, raising funds, learning, and gaining inspiration from other women’s movements around the globe (such as in Liberia, Rwanda, Colombia, the Philippines, and more). The resolution further assists in expanding women’s accessibility to knowledge about issues like women, peace, and security (through initiatives like Building a Shared Future, Marching for Peace, and Young Politicians) and promoting activism.

Resolution 1325 is an opportunity for political activity, which explores women’s positions and encourages them to act for peace. Women’s activism for peace is a continuous activity. Hence, as suggested by Tamar Rappaport (2004):

We are required to explore under with conditions the potential linkage between women and peace is materialized, intensified

or dissolved, and what is its meaning in light of the violent, coercive security discourse and the gender regime in Israeli society.

What brings some women to stick to feminism and peace inducing activity, and what prevents women who are located further than

the hegemony (due to class, ethnicity or age) to connect to them. (p.3)

In addition to the contributions mentioned above, intensive women’s activity in peace organizations is also a form of resistance against the patriarchal and hegemonic structures in Israeli society — a resistance that rejects traditional representations and stereotypes concerning women’s roles in peace and security processes, determined to raise public discourse about peace again and again, keeping alive the flame of hope for peace.

This article is based on a longer paper prepared for the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, which includes 15 interviews with peace activists, a literature review of the field, and personal testimony from field work that was co-authored by Nurit Hadgeg.