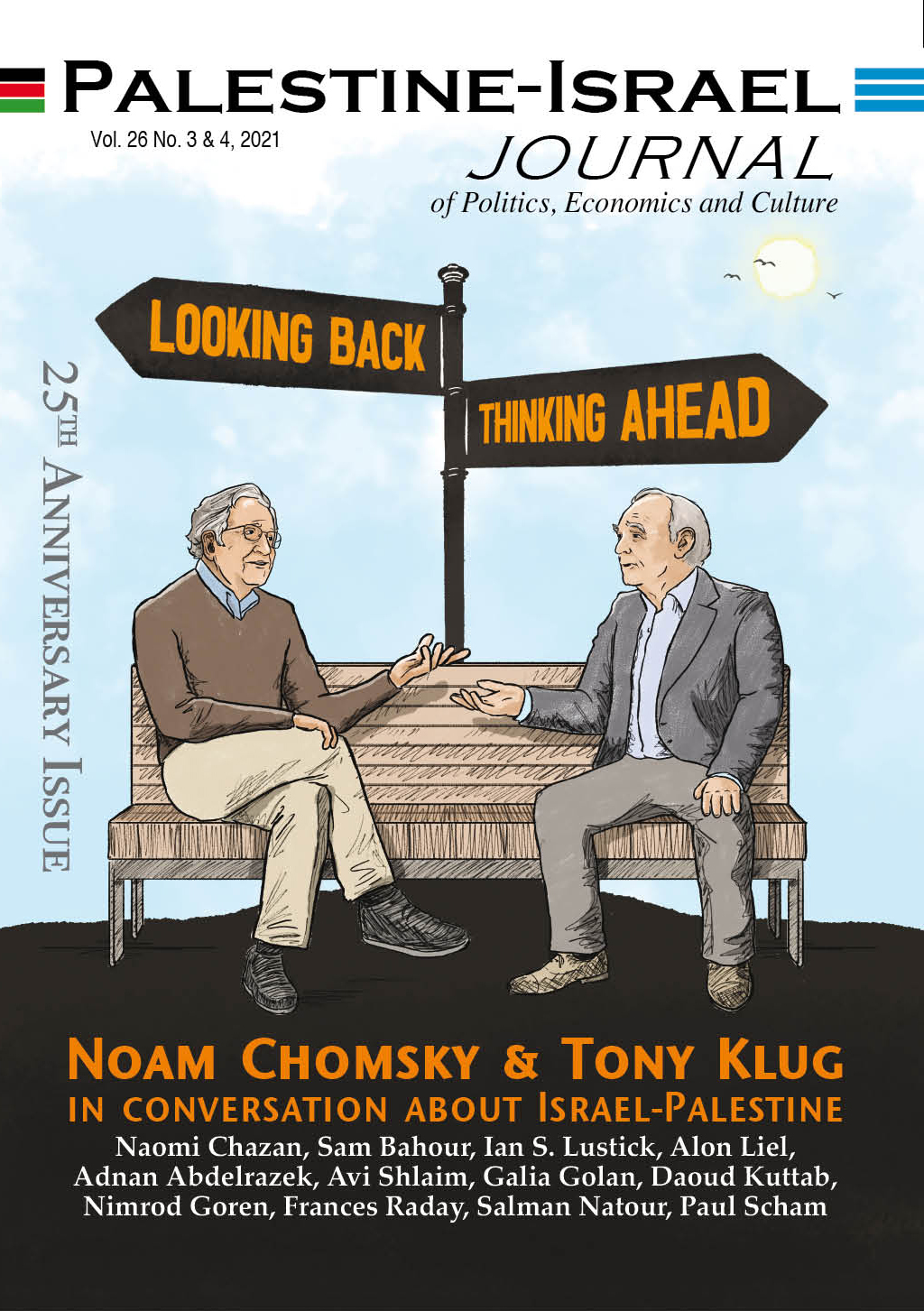

For nearly a year, world-renowned public intellectual Professor Noam Chomsky (US) engaged in a wide-ranging email conversation focused primarily on Israel-Palestine with veteran Middle East analyst, Dr Tony Klug (UK), a frequent contributor to the Palestine-Israel Journal and an international board member. The correspondence, which was sparked by Klug’s article, which was published in PIJ (Vol. 25 No. 1&2, 2020), “Should Trump’s ’Vision’ for Israeli-Palestinian Peace Be Taken Seriously?” (Summarized below), prompted an initial response from Chomsky. Klug’s reply provoked a further Chomsky response, and the stage was set for a fascinating, free-wheeling tour d’horizon that surveys both historical and contemporary events, vacillating between areas of broad agreement and points of candid disagreement. What needs to be done by different parties to change the current awful reality and bring the long-running clash finally to a tolerable end is also probed.

Summary of Tony Klug’s PIJ article on the Trump “vision”:

Trump’s “Deal of the Century” is an exercise in sophistry, concocted by dyed-in-the-wool ideologues with a one-dimensional lens. It panders to Israel’s ultranationalists and is an ultimatum to the Palestinians to accept their lot as a defeated people so that Israeli rule over them may be entrenched indefinitely. But the Palestinians will not be defeated. If enacted, the scheme would breed endless strife. It would dash Palestinian hope and perpetuate their suffering; it would cast Israel and its citizens as pariahs; and anti-Jewish sentiment would spread within and beyond the region. Trump’s construal of the plan as portending “win-win opportunities for both sides” is self-serving baloney. In reality, it is a lose-lose-lose scenario. Both the Palestinian future and Israel’s acceptance in the region rest primarily on the decades-old occupation coming to a swift and complete end.

The plan’s launch conference was marked by ignorance, deceptions and a string of faux pas, exemplified by Trump’s inept reference to the “Al- Aqwa” Mosque (apparently confusing a sacred Muslim place of worship with a water feature!) In general, the plan attests to the unsuitability of the US to play the role of honest broker between Israelis and Palestinians. Never has this been truer than now. Other parties must get involved, for this is a matter with global repercussions.

Trump disingenuously claims his plan presents “a historic opportunity for Palestinians to finally achieve an independent state of their very own,” within a vision of a “realistic two-state solution.” By employing the two-state terminology, he is plainly trying to pass off the plan’s brutal annihilation of the international consensus for a Palestinian state alongside Israel as the very opposite: its optimal fruition. The smart response of other governments would be to swiftly recognize a Palestinian state alongside Israel, with its capital in East Jerusalem. International civil society needs to consider what constructive role it could actively play.

A rejuvenated Arab Peace Initiative (API) – long ago endorsed by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and all Arab states — could provide the framework. Its offer of comprehensive peace and full diplomatic relations between Israel and the whole Arab world would once have had Israelis' dancing in the street. Despite more than a hundred retired Israeli generals endorsing the API as a basis for talks, so far successive Israeli governments have been quite dismissive of it, with the phony excuse that it is a diktat.

A positive feature of the Trump plan is that it projects its ultimate vision at the outset rather than seeking to move forward incrementally through step-by-step bargaining without a clear notion of the destination, an approach that doomed previous processes from their inception. In this sense, the Trump plan has more in common with the approaches of earlier Arab initiatives: the 1977 Sadat initiative, the PLO’s 1988 “historical compromise,” and the 2002 API. Commencing with a vision of the endgame – sketching out the horizon — has always been the more promising approach in principle, provided it took fully on board the key interests and aspirations of all parties or incorporated a mechanism for doing so. On this score, the Trump “vision” again fails abysmally.

Chomsky:

Thanks. One reservation. I don’t think the API would have ever led to Israelis “dancing in the streets.” Syria-Egypt-Jordan offered Israel virtually that in January ‘76, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) resolution that drove the Rabin government to virtual hysteria and that the US vetoed. And many similar options since. As Rabin put it clearly in ‘76, the plan is off the agenda because Israel will not envision any Palestinian state. Shamir-Peres put it even more clearly in ‘89, in response to the ‘88 Palestinian declaration of independence. There can be no “additional Palestinian state” between Israel and Jordan (additional, because Israel declares Jordan to be a Palestinian state). Pretty much affirmed in the Baker plan a few months later. Peres affirmed the same thing in his final press conference in ‘96. The first recognition of a possible Palestinian state that I’ve been able to find is by the incoming Netanyahu government. In an interview (Palestine-Israel Journal, summer ‘96), Netanyahu’s Minister of Information, David Bar-Illan, said that if the Palestinians want to call the fragments left to them “a state,” that’s OK – or they can call it “fried chicken.”

Klug:

I take your point about the positions struck by Israel's political leaders, but the reference was to ordinary Israeli people in a bygone era. This said, even the stances of Israel's leaders were not quite as simple as that. Some of them were on a journey, even if the destination was uncertain. This was true for the later Rabin (still travelling when assassinated) and Olmert but, surprisingly, for Shimon Peres, too. I have been doing some research on this recently for a book I am endeavouring to write. His is an interesting case study.

Chomsky:

I wonder. I saw a few comments by intellectuals – notably Amos Elon – about the “panic” in Israel when Sadat started making his peace offers, but never saw any indication that ordinary Israeli people were enthusiastic about opportunities for a two-state settlement, including the cases I mentioned – the ‘76 Syria-Egypt-Jordan two-state offer (repeated in 1980), the Palestinian 1988 proposal, and others like the Fahd and Saudi and Arab League proposals. Or that they even reacted when Prime Minister (PM) Rabin flatly rejected any such possibility, or when Chaim Herzog went beyond, charging (falsely) that the PLO had “prepared” the ‘76 offer in order to destroy Israel and that the Fahd plan was even worse. My impression is that the public was enthusiastic about the expansion, though there were some who issued firm warnings against it, especially Yeshayahu Leibowitz. My friend Israel Shahak at the time was viciously attacked at the University and in the press for even daring to talk about Palestinian rights (it changed much later, after the first intifada).

Klug:

For years, Peres was wrongly portrayed in the west as a peace dove. But, in later years, judging from his public statements, this image wasn't entirely false. He was anything but a peacenik in 1975 when he proudly unveiled his “federation” plan that would comprise Israel, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip “in which the inhabitants of the latter two areas would be accorded the maximum autonomy.” He claimed his plan constituted “an honourable solution for the Arabs themselves,” and maintained that it “provided for the first time a constructive Israeli proposal for resolving the Palestinian question.” A notable concession in his eyes was that the Palestinians in the Arab areas “could call themselves Palestinians if they chose!” That he termed it an “Israel Federation” was further evidence of how remarkably insensitive it was to Palestinian needs, interests and desires. (Definite echoes of these sentiments in the Trump plan.)

Following Sadat's visit to Israel in 1977, Peres outed himself (falsely) as a “dove.” A year later he was still proclaiming “Jordan is also Palestine… I’m against two Arab countries and against another Palestinian country, against an Arafat state.” You have pointed out there was no change in 1989 or 1996.

Peres was clearly conflicted, but slowly it seems he was becoming better tuned to Palestinian needs. Without his influence, it is unlikely that the 1993-5 Oslo Accords (however flawed) would ever have seen the light of day. In February 2002, reflecting on his 1975 “federation” plan, he told the Irish Times “We thought that autonomy is basically, almost independence … Today we discover that autonomy puts the Palestinians in a worse situation. We have to give them equal rights, equal recognition. We cannot run their lives, their economy.” In an interview on 18 December 2014 (two years before he died), he was even more explicit: “We are for a Palestinian state.”

He was not the only leading Israeli, Palestinian or Arab political figure to start off in one place and end up in another place (I could quote several top Palestinian leaders in this regard, starting with Arafat). There is nothing necessarily wrong with this, but it underscores the perils of snapshot quotations drawn from different points in time, however accurate they may be in and of themselves. The reality is very often more complex as I am finding out as I continue to research these matters.

Chomsky:

Seems to me that the reality is pretty clear. In the crucial decade of the ‘70s, Israel made the fateful decision to choose expansion over security and diplomatic settlement. That continued through the ‘80s. Israeli leaders, including Rabin and Peres, were adamant in flatly rejecting every peace offer, none of them perfect perhaps but surely a serious basis for negotiation. And the public seems to have gone along. Oslo was understood, correctly, as a way to subordinate Palestinians to Israeli domination. The Declaration of Principles didn’t even mention Palestinian national rights as a long-term objective. Peres and Rabin remained adamantly and openly opposed to any form of Palestinian state. Peres in his last press conference on leaving office in ‘96. Labor began to tentatively talk about this as a possibility in the late ‘90s, for the first time as far as I’ve been able to determine.

Yes, in later years Peres presented himself as a dove. But before that he was a leading advocate of settlement deep in the West Bank (Zertal and Eldar give extensive information on this). And after Rabin’s assassination, he was portrayed as aiming for political settlement, but his actions and statements up to the assassination seem quite to the contrary.

A mythology has been created about Israel’s yearning for peace but they had no counterpart to deal with. That seems to me far from the truth.

Klug:

I can only tell you that I was co-organizing an international symposium in Tel Aviv in 1977 when Sadat flew into the country. I had been in Egypt a couple of months earlier and returned there a few weeks later for the socalled Egypt-Israel peace conference. The mood in Israel when the Egyptian plane entered Israeli airspace was hugely emotional. Tears flowed, there was a mood of disbelief (and more than a little suspicion in some circles) and much rejoicing. People were indeed effectively “dancing in the streets.” The “Pharaoh” told them their presence in the area was legitimate and welcomed them back. But there was a Palestinian price (and of course an Egyptian price) and many, if not most, Israelis appeared ready to pay it at the time if it meant genuine peace and acceptance.

Menachem Begin, who it so happens had been elected as Israeli prime minister only a few months earlier, often gets undeserved credit for the peace treaty that was eventually signed. But his ugly antics at the press conference in Egypt subsequently ruined the initially warm mood among many Egyptians. I witnessed this personally and wrote about it in New Outlook at the time.

The cold telling of events in later years by people who were not on the ground can obscure the living reality in real time. I have discovered over the years that there is enough chapter and verse in this conflict for people with firm predilections to score whatever points they want by selecting evidence, even authentic evidence that supports their case. That's one reason why opinion is so polarized. My support for the national and human rights of the Palestinian people is long-standing and well-known, but I cannot deny my own experiences with either of the two peoples. Official documents tend to tell only part of the story and sometimes miss the most important parts.

Chomsky:

You’re absolutely right about the mood, but it’s worth bearing in mind what the mood was about. There was no acknowledgment of Palestinian rights, let alone a Palestinian state. Peace? Everyone’s in favor of that. But on what terms? If Israelis were willing to pay a price, they kept very silent about it. On the Egypt-Israel peace treaty, “credit” is an odd word. The peace treaty put no constraints on settlement and said nothing about Palestinian rights.

It’s true that it recognized that the policy of the Labor government, extended under Begin, to take over and settle the Egyptian Sinai under Labor’s Galili protocol, was untenable. That realization dawned among Israeli planners after the near disaster of the ‘73 war, precipitated by the US-Israeli refusal to respond to Sadat’s peace initiatives. With that hope abandoned, Israeli planners and strategic analysts recognized that the next best option was to remove Egypt from the conflict so that Israel could proceed, without impediment, to settle the occupied territories and to attack Lebanon, as it proceeded to do – meanwhile flatly rejecting every Arab peace initiative that affected the occupied territories, like the Fahd plan, the 1988 declaration of independence, etc., until the late ‘90s. This was bipartisan. Sharon was more extreme, but Peres and Rabin went along all the way.

In short, I quite agree with you about the mood, but again, it’s worth bearing in mind what the mood was about.

Klug:

I’m not sure whether or to what extent we’re agreeing or disagreeing here. I’ve been referring to the mood of the people. Your emphasis seems to be more on the mood among the political elite, although I might be wrong about this. A principal key to progress was always to outmanoeuvre Israel’s obdurate leaders. A primary reason Sadat’s 1977 initiative progressed (in contrast with the earlier efforts you cite) was that in this case, he cannily went over the head of Begin and his government by appealing direct to the Israeli people.

In effect, he cheated on history by flying in, out of order, and giving them an advance taste of peace while simultaneously setting out the conditions to earn its future fruits. He got the psychology (as he observed himself). By so doing, he snatched control of Israeli public opinion from the Israeli prime minister, who never got over it (as he confessed to Amos Oz). Sadat demanded every last grain of sand back in return for full peace. Begin weaved and ducked, demanding a bit here and a bit there. But Sadat stood firm and Israeli opinion backed him and together they drove the process forward.

When the Saudi plan/Arab Peace Initiative was launched in 2002, I argued they should take a leaf out of Sadat’s book and follow his example. I believe it could have made all the difference. Simply uttering the words without making any proper attempt to convince the other party (the Israeli people, in this case) of the sincerity of the intention (or more profoundly, the overt change of intention) would achieve nothing. The small print of the API made it clear that the target of the Arab promotional effort was Western and international power structures, not Israeli public opinion. For the latter, it was a case of take it or leave it. That was a profound error, if they were serious.

This attitude doomed it from the outset. Of course, they were in no mood to follow Sadat, whom they still considered a traitor for doing a separate deal with Israel (although at one time or another Syria, Jordan, the PLO, and more recently Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states have each attempted to do precisely that!) So instead of the Sadat precedent offering a noble guide, it still stood — a full quarter-of-a-century later — as an ignoble deterrent. They were blinded by it. This was a huge mistake, even if understandable in the context of internal Arab politics.

I don't dispute the thrust of your case about the intransigence of Israel’s political leaders (although there were exceptional moments) and have written at length about this myself. But any analysis that omits the strategic and tactical failings of Arab political leaders (more Arab state governments than Palestinian leaders in my view, although none deserves to be let off the hook entirely) is incomplete in my opinion.

In any case, the situation has moved on, and we are now faced with a de facto one-state reality, which is on the verge of becoming further entrenched, although to what extent is not yet certain. The compelling question in the short term is whether this single state/single sovereignty will move in an apartheid, unitary, or binational direction. The terminology, I believe, is critical, as time and again I notice “binational” and “unitary” being used interchangeably as if they mean the same thing, when they categorically do not. The terms are used far too loosely, rather like “two-state solution” and its oxymoronic offspring “one-state solution” have been for years, to the detriment of intelligent debate.

One could imagine, for example, a possible future for a federal binational state (or maybe a confederal arrangement), whereas it is highly doubtful that a unitary “democratic secular” state, whereby everyone is “atomized” down to the level of the individual (to quote my fellow panellist Professor Bernard Wasserstein at a seminar some years ago), is even plausible as there is very little authentic support for such a set-up by either Palestinians or Israelis. It would require them to set aside their deeply felt national sentiments and possibly some of their customs, too, critical factors not always grasped by the contemporary narrow Western mindset – whether of the right, the left, or the centre — intent on imposing its own values, systems and structures on cultures from other regions of the world. We have had more than enough of the mayhem that often follows.

In the meantime, there would be a compelling moral imperative (if not a legal imperative, too, under international law and human rights conventions) to agitate for equal rights for everyone living under the same sovereign authority, for as long as that is the case, without requiring the Palestinians to forfeit their hopes for eventual self-determination or Israelis to give up on theirs. These objectives – independent states/confederation/federation — are often posed as alternatives but, to the contrary, they could be stages. One set of rights should not be used to cancel out the other set.

I don't think the Palestinians are ever likely to give up on their aspiration for statehood (nor, for that matter, will most Israeli Jews), regardless of what seem to be indicated by misleading snapshot polls. This would not be the first case of a state or a prospective state disappearing from the map, but not in people’s hearts, for a period of time for geopolitical reasons and subsequently reappearing (Poland is a compelling example). Equal civil and political rights within a common sovereign entity, while unassailable, are not necessarily enough or the end of the line, as the breakup of Czechoslovakia demonstrates, and as the UK and Spain, among others, might in the future demonstrate further.

There is a new debate to be had. I hope it will be constructive.

Chomsky:

True, the people wanted peace and were therefore overjoyed that Sadat was publicly saying “I love you.” Apart from educated sectors, people were generally unaware of the Arab peace initiatives through the ‘70s that Israel had flatly rejected. For the public, the peace that they were being offered by Sadat required no sacrifice, except potentially of the takeover and settlement of the Egyptian Sinai under Labor’s Galili protocols, viciously implemented by Sharon. While the people were overjoyed about Sadat’s offer of peace with no sacrifices, they also voted for Begin and Sharon.

On the current situation, Israel is consummating the Greater Israel project of the past 50 years, always pursued relentlessly by Peres, Rabin, and on to the right: take over what is valuable in the West Bank (and before it became too costly, Gaza – and of course Golan), but not the Palestinian population centers. And always step by step, “dunam achar dunam,” under the radar. In the areas to be integrated into Israel, the population is being slowly thinned out by various measures that make life unbearable or else being confined to tiny enclaves, by now 165. This way, there will be no ‘demographic problem.’ In fact, as Greater Israel is more closely integrated with Israel proper and eventually annexed, the percentage of Jews may be even higher than it is today.

Except for some religious extremists, there’s little support for one state and an apartheid struggle, and no international support. Why should Israel want to take over Nablus? Of course, as in the standard neo-colonial pattern, something is offered to Palestinian elites. In Ramallah, one can go to fine restaurants, etc., just as in any neo-colony. Meanwhile, the Israeli population continues its drift to the far right, as polls consistently show. Even to “chosen people” fantasies. Israel is by now almost the only country where the young are more reactionary than the old, who still have some memories of the faded social democracy and the dreams of their youth.

I’ve been writing about all of this for 50 years. I don’t really expect anyone in the “peace camp” to read it. Illusions are much more comforting, but I don’t think they are wise. Failure to see what was clearly happening in the ‘70s only encouraged Israel’s fateful decision then, across the spectrum, to prefer expansion to security and the fulfilment of Leibowitz’s dire forecasts.

You’re quite right about failures on the Arab side, particularly the PLO. I’ve also been writing and speaking about that for years. Attitudes have changed among the general public here, quite considerably, and could lead to changes in US policy if a genuine solidarity movement developed. But it’s time, I think, for illusions to be swept away.

Klug:

Your comment about sweeping away illusions reminds me of a packed Palestinian-Jewish meeting held in London in the wake of the 1991 Madrid Conference when speaker after speaker denounced the bias of the press. A straw vote was taken. Sure enough, almost everyone was evidently of the same mind (bar a small posse of irate journalists). The audience was then asked who the bias favoured. Roughly half thought it was definitely slanted towards Israel while the other half was equally convinced it favoured the Palestinian and Arab sides. The media contingent breathed a sigh of relief as the apparent consensus turned out in reality to be quite false.

I agree with you, of course, about the importance of sweeping away illusions. The problem is so does everyone else. It has been part of my life's work to shoot down the potent myths nourishing this conflict, on all sides of it, but you can be sure that many of them out there think the likes of you and the likes of me are crammed full of them ourselves. Maybe they have a point. For myself, with the way things have turned out, I suppose I ought to plead guilty. When I first advocated a Palestinian state on the West Bank and Gaza after the 1967 war, I was certain its materialization was inevitable. And imminent. So much so that I berated my publisher for delaying the publication date of my pamphlet by a few months to January 1973 on the ground that we might miss the boat altogether if we wait that long!

Now it is said by some, decades later, from the far left to the far right and many points in between, that the two-state idea was always fallacious. I accept, of course, that it hasn’t happened and that the prospects are not exactly rosy, but I don’t accept that that means it was foredoomed. Israeli governments may never have been keen on it, the Israeli people lukewarm and Palestinians hesitant in their support, but it was the indifference, ineptness, or gross negligence of the international community that scuppered it. I had a direct involvement with some of that history, which I will be elaborating in a book I am currently writing which traces the genesis and evolution of the two-state idea following the 1967 war.

I still do not believe there can be a “solution” that is not constructed around the scaffolding of self-determination for both peoples. I fear that we are now moving into a state of perpetual conflict, sustained repression, and mutual fear, with toxic global overspill. I have been warning of this prospect for many years if the two-state paradigm were to conclusively fail. But I would like to think that the magic thinking that still swirls around will do less damage to the debate ahead than it has done in helping to destroy the only outcome which, in my opinion, ever made any sense. Some hope! I once thought I would see this conflict out. It is now very clear that it will see me out. And, I dare say, maybe even you (although I hope you continue to prosper to a very old age!)

Chomsky:

Like you, I’ve long supported a two-state outcome, and in fact still do. The only realistic alternative is the Greater Israel project that both major political groupings in Israel have been pursuing for 50 years, very different from the ‘one-state’ delusions that are now popular. To pursue what options remain, we have to be clear about the history, including very explicit and adamant bipartisan Israeli rejection of two states from the early ‘70s, when Israel made the fateful decision to choose expansion over security, with the exception of a few years around 2000 when there was some debate about this.

I think that may be our only point of difference.

Klug:

You may be right; except I don’t feel I can go along with the view that all Israeli prime ministers, from both parties, were unambiguously Greater Israel aficionados. The nuances are important because that’s where international leverage had a role to play that could have made all the difference. I’m sure a treatise could be written, drawing on their own pronouncements and actions, on how Rabin, Barak, Olmert, and Peres were all Greater Israel hawks, but a treatise could also be written, drawing on other evidence and personal testimonies, to show they were a lot more flexible and prepared to contemplate a Palestinian state if that would end the conflict.

Rabin's killers feared that was exactly where he was headed, despite his earlier exhortations to “break their bones.” That's why they murdered him. His participation at the peace rally where he was assassinated shortly after joining in the singing of a popular peace song were indicative of the distance he had already travelled. Who knows where he would have ended up? Barak's supposedly “generous offer” at Camp David, leaving Israel with around 10% - 13% of the West Bank, fell far short of his self-serving depiction of it, but he was prepared to divide the already annexed Jerusalem and, too late, he did shift his position at Taba later the same year to around 3% retention. Olmert, the Likud prince who had voted against the peace treaty with Egypt, travelled a huge distance in his talks with Abbas, asserting that the alternative to a Palestinian state was apartheid. Peres, the false dove, eventually concluded, in the last two years of his life, that a Palestinian state was the only way forward.

I believe it is a category error to lump these more pragmatic leaders with the true Greater Israel ideologues of Begin, Shamir, Netanyahu, and arguably Sharon (excepting Gaza for “demographic” reasons). But even they were susceptible to outside pressure on the rare occasion there was any. And this is the rub. The main culprit, in my view, was the failure of external powers — principally the US but the UK and other European governments as well — to (a) adopt peace plans that were not conceptually flawed and doomed from the start, and (b) apply robust, smart incentives and penalties. More solid peace plans were proposed to Western powers but consistently were not taken up. I was involved in a few such initiatives.

I believe there were a number of opportunities, under different Israeli prime ministers, when the right sort of pressure and intelligent international involvement could have been effective and brought what I used to call “this eminently resolvable conflict” to a successful conclusion.

Now, in the impending new reality, there are many questions floating around about what to do but very few answers, other than from the specialists in muddled thinking. Key to future progress, in my view, will be progressive alliances between Arabs and Jews, Palestinians and Israelis, as long as they don’t drift too far from their respective mainstreams.

Chomsky:

We have to distinguish two periods, before and since 2000. I’ve looked through the record pretty carefully and reviewed it in print, with sources. If you check, I think you will find that it includes every PM until 1996, Peres’s last term, which he concluded with a press conference in which he stated that there will never be a Palestinian state. Then comes Netanyahu, with the comment I quoted. By the late ‘90s, there was some talk about the possibility. Then Barak and the Taba conference, which seemed to be getting somewhere according to participants until Barak cancelled it. The later record is one of much less uniform rejectionism.

If there’s anything I’ve missed, I’d very much like to know. I don’t see any category error, but of course we have to distinguish pre- and post-2000.

Separate point. According to the best sources I can find (Pundak and Arieli particularly) there was never any 3% offer or anything like it.

Klug:

I don’t think the time distinction you make is the only meaningful distinction. The ideological rigidity (or sheer stubbornness) of different individuals was also critical. Likud leaders in general tended to be much less flexible and accommodating than Labour leaders, but this was not uniformly so. On the one hand, there was the ex-Likudnik Ehud Olmert, who ended up as “dovish” as any of them, if not more so. On the other hand, there was Golda Meir, who rejected even the notion of a Palestinian people, let alone a Palestinian state (I spoke to her myself about this in 1973 when, over a long private lunch, I handed her a copy of my pamphlet which called for a Palestinian state alongside Israel; she glanced at the cover and passed it on to a nearby aide).

Her predecessor, Levi Eshkol, was a lot more open-minded, even offering in February 1969 to talk to Fatah, widely viewed in Israel at the time as a band of terrorists, with Arafat the chief thug. His offer was never put to the test, though, as he suffered a fatal heart attack a few days later. Golda’s assumption of the premiership put all further talk of a Palestinian state or negotiating with “terrorists” into cold storage for nearly a quarter of a century. Labour Party Secretary General Arieh (Lova) Eliav did favour a Palestinian state, however, and promptly got his marching orders from her. There were other nuances, too, which are an important part of the record.

It is also worth noting that the time distinction you observe was not particular to Israel. The international community considered the Jordanian option the only option until 1988. It took until March 2002 for the UN Security Council to officially support a Palestinian state alongside Israel, echoed in the Arab Peace Initiative the same month. The Palestinians (PLO) themselves, of course, did not endorse the idea of a Palestinian state alongside Israel (instead of instead of Israel) until 1988, remarkably declaring five years later that it accepted Israel’s “right to exist” (I had never expected them to go that far). So, as frustrating as it was for those of us who had been calling for two states for years, the Israelis were not seriously out of step timewise with the rest of the world on this issue.

The plans that then emerged from the US government, such as the Road Map (30 April 2003) were conceptually flawed (http://www.hlrn.org/img/documents/The%20roadmap.pdf.) Incrementalism was absolutely what not to do. Someone compared it to trying to jump over a huge chasm in two or more leaps! About three months earlier, together with colleagues at the Oxford Research Group, I had put forward a proposal for a temporary international protectorate over the West Bank and Gaza Strip as a prelude to Palestinian independence.

It attracted quite a lot of interest, which included media interviews, invitations to address numerous meetings, an article in Open Democracy (https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/article_1207jsp/), republished on other platforms, and an op-ed in the Guardian (15 January 2003) by the influential columnist Jonathan Freedland, under the title “At last, a fresh idea.” Freedland commented: “Debated in policy circles in Washington and London, this new plan is said to be gaining currency on the Israeli centreleft as well as winning a warm hearing in Palestinian leadership circles. Its advocates include people who have rarely agreed on much before, but who suddenly believe that, in this most hopeless of conflicts, they have at last hit upon a plan which might work.” https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2003/jan/15/foreignpolicy.world

A short time after our proposal appeared, a similar, although less farreaching, plan was put forward by Martin Indyk, published in the May/June 2003 edition of Foreign Affairs: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/israel/2003-05-01/trusteeship-palestine

Despite all the interest and support, these proposals got crushed by the US Road Map juggernaut, the self-evident weaknesses of which were obscured by the fog of wishful thinking and self-deception. Like most US proposals, it also suffered from the urge to exploit an ostensible peace process to promote other foreign policy aims, such as gaining an advantage over its strategic rivals, rather than focus strictly on resolving this eminently resolvable conflict.

Further, the absence of an effective enforcement mechanism in the shape of smart potential rewards and smart threatened penalties foredoomed all international peace initiatives and rendered negotiations ultimately pointless. The idea that all that was needed was friendly mediation or that the parties, seated around the same table, would somehow come to understand each other better and display enough goodwill to get an agreement over the line was always bunkum. So, too, was a programme of “confidencebuilding measures” in an occupation situation, or the belief that violence was the main impediment to ending the occupation rather than seeing that the violence was a product of the occupation. Violence has more of less ceased in recent years, but guess what?

So, as we observed previously, and not to let Israeli governments off the hook, there is plenty of blame to go around in failing to achieve a Palestinian state.

As for the 3%, it is worth looking at the Moratinos “non-paper” on the Taba talks, published in the Journal of Palestine Studies (click on the link, then open the PDF document): https://online.ucpress.edu/jps/article/31/3/79/52925/The-Taba-Negotiations-January-2001

There is a reference there to a 6% Israeli proposal (which itself was a considerable improvement on the proposal at Camp David). But I believe this was before land swaps, which some reports argued brought the figure down to 3% (although this figure might have included the projected passage between Gaza and the West Bank). The Palestinians, not unreasonably, insisted on zero per cent and, from memory, I believe this was reflected in the subsequent unofficial Geneva Initiative.

Finally, what you say about Barak cancelling the Taba conference is technically true, but the intifada was well under way by then and Barak was about to be trounced in the Israeli election by the notoriously hawkish Sharon, whose earlier incursion into the Temple Mount / Haram al-Sharif compound, accompanied by several hundred-armed guards, had helped spark the uprising with the obviously deliberate (and successful) intention to undermine Barak.

Chomsky:

Eliav is the single exception, and he was very marginal as you know. Meir, Rabin, Peres were adamant rejectionists until the end (Peres shifted after he left office in 1996 and tried to craft an image as an elder statesman, but that’s obviously irrelevant). There were no nuances pre-2000, and it’s idle to look for them. Straight rejectionism, spearheaded by Labor in the ‘70s, which also insisted on settling the Sinai, building the all-Jewish city of Yamit, driving out thousands of inhabitants, razing mosques and towns to build kibbutzim. Labor’s Galili protocols, plans finally abandoned by Begin.

Again, in the 1989 Peres-Shamir coalition government that responded to the explicit PNC peace offer by declaring that there can be no “additional, Palestinian state” (my italics) between Jordan and Israel, on to Rabin’s escalation of settlements and rejection of a Palestinian state after Oslo and Peres’s final press conference, flatly rejecting any such outcome.

The international story simply makes the picture clearer. In January 1971, Israel rejected the international Jarring initiative, supported by Sadat, for a peaceful settlement with nothing for the Palestinians. The issue was Labor’s goal of settling the Sinai (the Galili protocols).

In January 1976, the UN Security Council considered a resolution, supported by Egypt-Jordan-Syria, calling for two states on the Green Line with guarantees for the right of each state “to exist in peace and security” with secure and guaranteed borders. There was of course room to negotiate, but PM Rabin rejected it out of hand, declaring that there will be no Palestinian state and no negotiations with the PLO. Ambassador Chaim Herzog practically went berserk. He claimed (falsely of course) that the resolution was “prepared” by the PLO in an effort to destroy Israel. It was vetoed by the US. The PLO condemned “the tyranny of the veto.”

With the Security Council blocked by the US, international debate then shifted to the UN General Assembly where there were regular resolutions with similar content, virtually unanimous, rejected by US-Israel, occasionally joined by some US dependency. It’s true that the UNSC didn’t accept a Palestinian state until 2002 – because the US vetoed such proposals in the Security Council and voted with Israel in the General Assembly to reject them, virtually alone.

There simply are no nuances. In the ’70s, Labor made the clear decision to choose expansion over security. There is no deviation from total rejectionism until flickers in the late ‘90s. Always fully supported by the US, some meaningless rhetoric aside.

There’s plenty of blame to throw around, but we should be clear about this very explicit record. Like you, I was frustrated by the failure to implement the overwhelming international consensus on a two-state settlement from the mid-70s.The overwhelming reason is US-backed adamant Israeli rejectionism.

Klug:

(Chomsky’s responses are interpolated in bold type)

I don't dispute your raw facts, but I do think they need to be contextualized and qualified.

Everything can always be presented in more detail, and when we do in this case it simply brings out more clearly what I said: flat rejectionism on the part of both political groupings in Israel until the late ‘90s, when there were some flutters of reconsideration, backed by the US in opposition to virtually unanimous global opinion.

I make these observations:

1. Regarding principled supporters of two states, I would add Beilin to Eliav.

That’s true. His MehiroshelIhud is a very valuable indictment of Labor’s rejectionism, up to the early ‘80s. But, of course, he was in the margins.

2. There were three prime ministers — Rabin (1993), Barak (2000), Olmert (2008)— who, with all their prevarications, were inching towards doing a serious deal with the Palestinians, either because of external pressure, internal pressure, Palestinian pressure (intifada), or belated recognition that otherwise Israel was heading towards apartheid and the death of the Zionist dream of a Jewish democratic state. All three of them were late (and not necessarily full) converts. Each of them was abruptly stopped in their tracks — by assassination, by a looming electoral defeat, and by imprisonment.

2000 and 2008 are irrelevant, for the reasons discussed. The issue is total rejectionism from the early ‘70s to the late ‘90s.We can speculate as to what might have been in Rabin’s mind. But his actions are clear. Oslo was flatly rejectionist in principle, not a mention of Palestinian national rights even as a long-term goal in the DOP (Declaration of Principles), underscored by limiting mention of UN Resolutions to 242 and 338. After Oslo, Rabin carried forward his policies of expanding settlements in the West Bank, formulating the strategy clearly. Carried forward by Peres, very explicit rejectionism, including his final press conference in office.

In Rabin's case, I was part of a small contingent that met Arafat in London shortly after Rabin had been assassinated. Arafat was visibly distraught, convinced that had Rabin lived they would have resolved the conflict on the basis of two states. That was his judgment. I can’t gainsay it. Olmert claimed that he proposed a net retention of 0.5% (excluding the West Bank/Gaza passage).

In short, from the early ‘70s to the late ‘90s, it is impossible to point to any departure from strict rejectionism.

3. Israeli politicians did not form a monolith. Sustained international pressure, notably US pressure, could have made the difference.

Absolutely. That’s what I’ve been writing and speaking about since the mid-70s, when full US support for total Israeli rejectionism became completely clear.

The hard-line Begin would not have withdrawn from Sinai (even though he was not ideologically committed to it) without a combination of external and internal pressure. But very little international pressure was applied to withdrawing from the West Bank throughout the length of the occupation. I encountered the flawed argument time and again that Israel's withdrawal from Sinai and then Lebanon and then Gaza proved that in principle Israel was willing to withdraw from all captured Arab land, including the West Bank, in exchange for peace. The Palestinians just had to stop their violence. For ideologues like Begin, Shamir, and Netanyahu (and to a lesser extent Sharon), the logic worked quite differently. Judea and Samaria were the prize. There was more scope with the more pragmatic leaders, but it wasn't exploited. On the evidence, I find it hard to go along with the view that there was nothing but persistent and undifferentiated rejectionism on Israel’s part (any more than there was persistent and undifferentiated Palestinian rejectionism, which is another common, and in my opinion equally erroneous, view but for which a case could and has repeatedly been made).

In short, the facts are unambiguous. As for the Palestinian leadership, I have far harsher criticisms than yours, but the facts are also clear. From the mid-70s, they took the position that they would accept sovereignty in any territory they could obtain, without relinquishing the right for more.

4. There appears to be an important nuanced difference between pre-1988 and post-1988 resolutions. Pre-1988 resolutions used such language as a “just solution,” “inalienable Palestinian rights to self-determination,” “right of return to homes and property,” “right to national independence and sovereignty in Palestine,” and “full withdrawal from occupied territories.”

That is simply false. The January 1976 Security Council resolution was quite explicit about a two-state settlement on the international border. To save you the trouble of looking it up, here are the crucial words:

That the Palestinian people should be enabled to exercise its inalienable national right of self-determination, including the right to establish an independent state in Palestine in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations: That Israel should withdraw from all the Arab territories occupied since June 1967. The appropriate arrangements should be established to guarantee, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations, the sovereignty, territorial integrity and political independence of all states in the area and their right to live in peace within secure and recognized boundaries.

Loud and clear. PM Rabin understood it perfectly, responding at once that there will never be a Palestinian state. Herzog went beyond, claiming that the resolution was “prepared” by the PLO in order to destroy Israel – false, of course, but it reflects the mood among the more dovish sectors – the “panic” that Amos Elon described. The resolution was supported by Syria, Egypt, Jordan, and vetoed by the US. The PLO condemned “the tyranny of the veto.” Matters shifted to the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA), where the US regularly voted alone with Israel (sometimes some US dependency) against the world on similar resolutions. Sometimes US rejectionism was so extreme that it became an object of ridicule, e.g., in Feb. 2011, when Obama vetoed a resolution backing official US policy on settlement expansion.

The only pre-1988 General Assembly resolution I have come across which explicitly refers to a Palestinian state was the one on 17 December 1981 which, with studied ambiguity, called for the “establishment of its independent sovereign state in Palestine” (no explicit mention of alongside Israel). I have now looked up the draft UNSC resolution of January 1976, vetoed by the US: [S/11940 of 23 January 1976 – Home – Question of Palestine] and note it did not unambiguously call for two states either, one next to the other (this is not nit-picking because it did make it explicit after 1988; see below), although I think you’re right that this was a reasonable implication.

The wording was explicit. There’s little point denying plain and explicit facts.

It would be surprising if Jordan did back a Palestinian state on the West Bank at that time, as the Hashemite monarchy was vehement in its own claim on the territory until 1988.

Call it what you will. That was the official Jordanian position, reiterated later. In 1988, Jordan renounced any rights over the West Bank but that’s consistent with their support for a Palestinian state, explicit since ‘76.

5. Compare those resolutions with General Assembly (GA) resolution of 15 December 1988, exactly one month after the Palestinian National Council (PNC) meeting in Algiers which, for the first time, called for a separate Palestinian state in the West Bank and Gaza and three days after Arafat addressed the GA expanding on the new policy and endorsing the 1947 partition resolution 181.

The GA resolution began by "Recalling its resolution 181 (II) of 29 November 1947, in which, inter alia, it called for the establishment of an Arab State and a Jewish State in Palestine ... Aware of the proclamation of the State of Palestine by the Palestine National Council in line with General Assembly resolution 181 (II) .. Affirms the need to enable the Palestinian people to exercise their sovereignty over their territory occupied since 1967 ...".

Considerably more ambiguous than the UNSC resolution of Jan. 1976, which was also far more important than a UNGA resolution.

And it’s worth adding the response of the Peres-Shamir coalition government to the PNC declaration: there can be no “additional” (!!) Palestinian state between Israel and Jordan, and the fate of the territories will be determined in accord with the guidelines of the Israeli government (endorsed in the Baker plan). That’s Peres the dove.

The GA resolution of 15 December 1988 was a watershed resolution as it was the first time as far as I can tell that a Jewish state in Palestine was openly affirmed (reaffirmed) in any of these resolutions alongside a Palestinian state to be established in the occupied territories (defined clearly as 1967 rather than possibly 1948). Although it took another 14 years for the Security Council to adopt the same two-state policy, it is really only from December 1988, following the lead of the PLO, that it could realistically be

said that two states became official UN policy (albeit with the opposition of the US and a large number of abstentions). It is a stretch to say that two states was the UN policy before then.

Nor did I say so. The UN could have no policy because of the US veto, and of course, the US dismisses the UNGA routinely on all sorts of issues.

Israel, of course, also opposed the 1988 GA resolution, but by 1993 it had started, begrudgingly, to show more openness towards the idea of a separate Palestinian entity …

Maybe secretly, but there is unambiguous and strong rejection in public, up to Peres’s last press conference in office.

… a development which the constant expression of international opinion by way of these resolutions and in other ways may have had an understated long-term influence, alongside other game-changing developments, notably the first intifada.

Klug:

I shall refrain from responding to every detail you have raised as my intent, like yours, is not to score points, and I’m concerned that we may unwittingly be descending into that. It may be more useful for me to contextualize my past (and present) remarks by explaining what has been motivating my involvement. From at least the inception of the Israeli occupation in June 1967, it has been one thing: to resolve this wretched conflict. That is what has driven me for the past fifty-plus years. Otherwise, I have no axes to grind.

The conflict dominated student politics at the local, national and international levels when I was active in those areas in the late sixties and early seventies. It was my baptism of fire. Subsequently, I travelled quite extensively in the region, became immersed, learned a lot, and acquired an affection for and close affinity with both peoples (which is not to say I never got infuriated). Some of my travels were research-oriented for my PhD thesis on the Israeli occupation, 1967-73. I have remained involved, on and off, in different capacities ever since then, although I confess to having made a number of unsuccessful escape attempts. I have written extensively about and around the conflict over many years and have been a consultant to both the Palestine Strategy Group and the Israel Strategic Forum.

My first work, published in January 1973, advocated a Palestinian state on the West Bank and Gaza alongside Israel, and I was closely in touch with the small number of Israelis and Palestinians who were proposing the same formula at that time. We were convinced that was the only way to resolve the conflict. I have put forward a number of peace plans of my own over the years and have campaigned for them at different levels, including with the governments of the UK, the US, Israel, and the PLO.

I witnessed and strongly welcomed the steady increase in support for a two-state outcome by other Palestinians and Israelis as the years progressed, until they became at one point a clear majority on both sides. I was perturbed when the proposal came to be known as the “two-state solution,” as I felt this terminology was misleading in more ways than one. One regrettable consequence was that the language gave birth to what I regard as an oxymoronic offspring, the so-called “one-state solution” (inasmuch as one state means a unitary state). When people today oppose or dismiss or ridicule the two-state idea, including some radical leftist Israeli Jews, I wonder how much they realize that the main implication of their stance is that the Palestinians cannot have their own state? This is the vital missing parameter. The Israelis already have their well-established state. It is the Palestinians who are stateless.

I mention all this as it might cast some light on my take on the matters we have been discussing. My interest in, for example, past events is not for the purity of the historical record, nor to push one interest over another, nor to prove a point, nor to condemn one party or another, nor to discredit this or that individual, nor for any other purpose except to resolve this miserable conflict. So what guides me and what I look for in examining events, including historical detail, are clues that indicate a vulnerability or a possible change of orientation, which may then be leveraged. The snapshot is of less interest to me than an indication of a change in the direction of travel, which sometimes may be quite subtle.

In the shadow of a recent change of PLO policy, the General Assembly resolution of December 1988, previously cited, was an obvious example to my mind of a detectable change in tone if not in substance, for reasons explained, but evidently not to your mind. Among other leading figures, the political development of Rabin – the reason he was assassinated – was for me another good example. I hold there was plenty of evidence he was on a journey, the destination of which was yet to be determined. But again you did not see it that way. I suppose we'll just have to disagree on such matters. We appear to agree at least about Olmert, which is another important case in point.

For at least the past 15 years I have been warning that we are in the last-chance saloon (the title of one of my past articles). It is possible that that saloon has now closed. But I'm not quite ready to give up on the quest to resolve the conflict as I still see potential opportunities, including the prospect of a change of orientation on my own part about how to end it. So I will continue to look for those vulnerabilities and opportunities while I can, until I spot the chance for another breakthrough which, in the history of this conflict, tends to come when least expected.

I take your word that Jordan supported the draft UNSC resolution of January 1976 calling for two states, but if you happen to have the source to hand, I would appreciate being apprised of it. The reason I find it surprising is that in the period that followed the 1967 war, King Hussein was vehemently opposed to a separate Palestinian entity on the West Bank. In a radio broadcast, his government denounced it as an “imperialist and Zionist design.” In March 1972, Hussein advanced his “federation” plan between the West Bank and East Bank. The plan was summarily rejected by the PLO, Syria and Egypt, which promptly severed relations with Jordan. But if you are right, less than four years later, Hussein was supporting a Palestinian state at the UN alongside Syria and Egypt. It is not clear how this squares with his relinquishing Jordan's claim to the West Bank only after the seminal PNC meeting in 1988. But I’m perfectly happy to be set right.

We do appear to see eye to eye, however, on the crucial difference that outside pressure could have made, particularly from the US, a contention apparently underlined by Israeli Trade Minister Haim Zadok in an interview with Uri Avnery shortly after the 1967 war. Reflecting on the interview in a 2018 article, Avnery affirmed that Zadok told him Israel would almost certainly, have buckled under concerted pressure:

Back in 1967, I asked, what part of the newly occupied territories the government was ready to give back (to Jordan). He replied: “Simple.

If possible, we shall give back nothing. If they press us, we shall give back a small part. If they press us more, we shall give back a large

part. If they press us very hard, we shall give back everything.”

https://jewishbusinessnews.com/2018/04/29/uri-avnery-real-victor/

This is why I pin the major blame on the US and other outside powers for the disastrous status quo. It was in their power to have prevented it from developing. This does not, however, as you rightly say, let the Israeli political class off the hook.

If you have not come across the burgeoning Israeli joint Jewish-Palestinian group “Standing Together,” it is worth looking them up (link below). It is, I think, one of the few beacons of hope to have emerged in recent years: https://www.standing-together.org/about-us

Chomsky:

On Jordan, it was reported at once by the New York Times (NYT), https://www.nytimes.com/1976/01/27/archives/us-casts-veto-onmideast-plan-in-uns-council-americans-say.html, and in many other sources then and afterwards: “Representatives of Egypt, Jordan and Syria attacked the veto with varying degrees of harshness, Dr Ahmad Esmat Abdel Meguid of Egypt said it would hinder the peace process. Jordan's Sherif Abdul Hamid Sharif called it a ‘historic mistake’ and Syria's Mowaffak Allaf labeled it ‘a betrayal’.”

If you read further in this article and the background discussions, you’ll see it was supported by the Arab states generally. Again in 1980, then on in further Arab peace plans, all rejected firmly by the unwavering bipartisan Israeli leadership, including Rabin and Peres until the end. I don’t see any difficulty reconciling Jordan’s support for a Palestinian state with their maintaining their claim over the West Bank after the option was blocked by the entire Israeli leadership spectrum, backed by the US.

The important fact, at least for those of us concerned about Israel and the Palestinians, is that in the 1970s, beginning with Israel’s rejection of the Jarring initiative and forcefully with Rabin-Herzog’s rejection of the ‘76 option and later ones, the Labor Party and its Likud successor made a fateful decision: to choose expansion over security. You recall Leibowitz’s reaction, which I shared, though I wouldn’t have put it that strongly. At that point and since I’ve been writing that from that point on, those who call themselves “supporters of Israel” are in fact supporters of Israel’s moral degeneration and possible ultimate destruction. I’m sorry to see the prediction verified and think that those of us who are concerned should preserve the record accurately, without illusions.

One illusion of Palestinians and the diminishing number of Israeli doves (including the truly outstanding Gideon Levy) is the “one-state proposal.” Israel will never accept its disappearance (apart from some right-wing religious lunatics), and there is zero support for it, including Third World countries that are jealous of sovereignty. It serves as a cover for the Greater Israel project that Israel has systematically been constructing for 50 years, under the leadership of Peres, Rabin, Begin, Sharon, unremittingly until this millennium. No need to review what happened since. I’ve been writing about that repeatedly, in Palestinian journals as well, and speaking about it constantly, to deaf ears. On Rabin, I only know about his very clear public stance to the day of the assassination. On Olmert, it was post-2000 – there’s more to say about it, but I’ll put it aside.

Like you, I don’t think the game is over, though there are many obstacles – including the “Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement (BDS),” which is adopting self-destructive tactics and has pre-empted the space for a genuine Palestinian solidarity movement of the kind that might have grown out of Avnery’s earlier BD [boycott/divestment] initiatives. Thanks for the link. Didn’t know about them. Looks promising.

Klug:

(Chomsky’s responses are interpolated in bold type)

I am grateful to you for having drawn my attention to the January 1976 draft Security Council resolution and have now perused the wider debate on it (https://unispal.un.org/DPA/DPR/unispal.76nsf/0/D0242E9E210D937585256C6E0054DF8A). I acknowledge it is a significant brick in the story and don’t disagree that the draft resolution very clearly expressed the right of the Palestinians “to establish an independent state in Palestine.” But because of the US veto, it did not become official Security Council policy and therefore is not part of the official record. But it was an important snapshot of opinion.

It is far more than a snapshot. It is a revealing illustration of the consistent stand of the entire Labor-Likud leadership up until 2000, including the so-called doves, from dismissal of Sadat’s peace offers and rejection of the Jarring initiative through the rest of the century. Rabin’s outright rejection of a Palestinian state, forcefully enunciated in his rejection of this opportunity, persisted until his assassination. Herzog’s hysterical reaction speaks for itself. Peres, one of the main architects of settlement deep in the West Bank, took an even more extreme position, declaring that there can be no “additional” Palestinian state.

Yes, it’s not part of the official record because the US blocked it, as it continued to do through the century and in other ways since. The sole serious departure was Clinton’s parameters, quickly abandoned.

Don’t know how to say this more clearly. In your search for private feelings, you are missing the crucial fact that in the 1970s, with firm US backing, Israel made the fateful decision to choose expansion over security, with enormous consequences: One is of course avoidable security problems, another is the moral degeneration that was predicted (Leibowitz and others, me, too, for what it matters), Israel’s decline from an admired social democracy to an international pariah and the darling of the far right. And, of course, crushing of Palestinian hopes.

The forceful rejection of peace by the US-Israel in ‘76 is a dramatic illustration – of stable and unchanging policies.

… The problem with snapshots, however, as I’ve occasioned to mention before, is what they don’t reveal. Anyone who reads the record of the debate could be forgiven for gaining the impression that Egypt, Jordan, Syria, and the PLO were in harmony on these matters and sincere in their support of a Palestinian state alongside Israel (which was the implication of the draft resolution).

The “snapshot” reveals with complete clarity that Egypt, Jordan, and Syria supported the resolution without reservations. It wasn’t an “implication” of the resolution; it was explicitly and precisely affirmed. The only person who claimed that the PLO was in harmony was Herzog. Of course, they were not. The PLO at the time was moving towards agreeing to accept any territory granted to them, as a base for further expansion – much like Ben-Gurion in ‘47.

Yet in reality, the Palestinian world as a whole and factions within the PLO had yet to reconcile themselves to the existence of Israel.

Completely true, but irrelevant to Israel’s fateful decision to choose expansion over security, rejecting the peace offer of Egypt, Syria, Jordan.

Writing only a few months earlier, in April 1975, Said Hammami was probably the first PLO official to speak out openly on this topic (and paid the ultimate price for his “treachery” three years later at the hands of a breakaway faction of the PLO). A highly influential article by the heavyweight Palestinian scholar Walid Khalidi in support of the two-state idea appeared only in July 1978, more than two years later. It took a further ten years for the PLO to adopt the paradigm as its official policy. January 1976 came much too early.

Jordan, as previously indicated, was vehemently opposed to separate Palestinian statehood when the idea was raised shortly after the 1967 war, and its leadership denounced and threatened anyone who favoured it. Thousands of Palestinians perished in “Black September” 1970 when the PLO was gunned out of Jordan. King Hussein's proposal for a federated United Arab Kingdom eighteen months later had only been on the table for under four years when the kingdom appeared to throw its support behind the 1976 UNSC resolution. It beggars belief. Another twelve years passed before Jordan officially dropped its claim to the West Bank.

Not “appeared” and it doesn’t beggar belief at all that Jordan decided to go along with Egypt and Syria. And it is consistent with their maintaining a claim to the West Bank after the entire Israeli political leadership made clear its unwavering rejectionism, with US support.

Less than two years after the draft Security Council resolution, the president of Egypt flew to Israel to make a separate peace. The treaty with Israel called for Palestinian autonomy, not statehood.

Correct. In the face of flat rejection by the Israeli left and the US, Sadat lowered his requests.

The Palestinians might have got a better deal had Arafat taken his place at the negotiating table in Cairo offered to him by Sadat, but he chose instead to participate in a Gaddafi-organized “rejectionist” conference in Benghazi.

Syria-PLO relations, in particular those between Assad and Arafat, were tempestuous, fluctuating over the years between mistrust and hostility. Arafat was physically expelled from Syria in June 1983, and all ties were broken. Dozens of his followers were detained for the next six years. Syria sponsored its own Palestinian guerrilla groups. Syrian support for the Palestinian cause tended to be very much on its own terms.

I am throwing out pieces of information here rather than constructing a thoroughly researched thesis. But there is a theme that runs through these and similar points, and I raise them to suggest that the ostensible unanimous Arab support for Palestinian independence in the January 1976 draft resolution might have had an element of disingenuousness about it. In the light of the histories and the many conflicting contemporary interests, I would be hesitant to accept at face value genuine across-the-board support

for an (Arafat-run) independent Palestinian state as early as January 1976 (although I had proposed it myself three years earlier), as there was ample evidence that this was not necessarily what the different parties then wanted. What might have made it easier for them to conceal their differences was the confidence that the motion would be vetoed by the US.

As for the US veto, there is much to be said on that. But I shall resist the temptation.

I’ll skip the above. Yes, all sorts of hidden feelings are possible. I’m talking about what happened, what opportunities existed, and what choices were made.

Returning to Rabin, you say you only know about his very clear public stance to the day of the assassination. But, having previously called for “force, might, and beatings” to quash the Palestinian revolt (he denied he said break bones), these were his words at the peace rally moments before he was assassinated:

“There are enemies of peace who are trying to hurt us, in order to torpedo the peace process. I want to say bluntly, that we have found a partner for peace among the Palestinians as well: the PLO, which was an enemy, and has ceased to engage in terrorism. Without partners for peace, there can be no peace. We will demand that they do their part for peace, just as we will do our part for peace, in order to solve the most complicated, prolonged, and emotionally charged aspect of the Israeli-Arab conflict: the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. This is a course which is fraught with difficulties and pain. For Israel, there is no path that is without pain. But the path of peace is preferable to the path of war ...”

In short, no departure from his total rejectionism, putting aside his cowardly claim that violence is the sole responsibility of the PLO. Not a hint of any Palestinian national rights. Of course, he wanted peace. Who doesn’t, on their terms? And the flat rejectionism of this statement is fortified by his programs of escalating settlement and explanation of the strategy behind it at the very same time.

I hold no brief for Rabin, but I don't see how you can maintain he was not on a journey. The huge crowd at the rally clearly felt he was. His assassin and many on the right felt he was. I think he was, and I think he thought he was. It's hard to know where he would have ended up. Maybe he had already gone as far as he was prepared to. Maybe not. But look at the distance Olmert travelled some years later when he, too, had to face the realities of Israel’s situation.

Yes, the crowd felt that he was on the way to peace – a peace that would implement the Greater Israel project that he and the other Labor leaders had been pursuing since 1970, but now with Palestinian acceptance. Why shouldn’t they have been delighted. And the right recognized that inherent in the Greater Israel project is leaving some shreds to Palestinians, which they reject, just as they reject Netanyahu’s annexation proposals today. That is the only journey for which there

is any evidence, including the quote you give.

Klug:

One of my favourite songs as a kid was the Gershwins’ It ain’t necessarily so: “the things that you’re liable to read in the bible, they ain’t necessarily so.” It was my first lesson in healthy scepticism, in not taking things at face value lest the deeper messages are lost. It is one of the tools I commonly employ in trying to make sense of the multifaceted Arab-Israeli conflict.

It lies at the base of my long-espoused contention that the Arab League’s famous three “noes” of Khartoum three months after the 1967 war may be better understood as meaning (or indicating) three “yesses”: yes to recognition, yes to negotiation, and yes to peace – but not yet.

That’s quite right I think, and it’s supported by the record. Nasser’s inching towards negotiations, Sadat’s acceptance of Jarring, and a lot more.

After the trauma of the 1967 setback, time was needed for the Arab world to come to terms consciously with the deeper meaning of their military defeat and Israel’s military victory. It was also a profound political, social, and psychological blow. Once the shock started to retreat, Arab states, as well as the Palestinians, would catch up with the new reality and be prepared to recognize and negotiate with Israel and offer it peace if certain conditions were met. Which, slowly but steadily, is what happened in practice. Taking

the three “noes” literally missed their true significance in the circumstances of the time (even though they were “explicitly and precisely affirmed”). To this day, Israeli hasbara cites the Khartoum declaration as evidence of abiding Arab intransigence.

On the other side, the intimations, or explicit declarations, of support for a Palestinian/Arab state by Levi Eshkol, Moshe Dayan, and Yigal Allon, among others, in the wake of the 1967 war have been cited by Israeli sources to show early Israeli munificence and instant Palestinian rejectionism.

Can you give me sources on these? The only example of Israeli munificence I know was the famous June 19, 1967, offer that Abba Eban made a fuss about and hasbara generally – all shown to be complete fabrication by Avi Raz. But if there’s anything else, I’d like to see it. That Palestinians were completely rejectionist until the mid-70s is not in question. I was sharply criticizing them for that, in print, from 1969.

On digging deeper, it becomes clear that by a “Palestinian state,” these Israeli leaders meant something quite different from a sovereign independent state on the West Bank and Gaza with Jerusalem as its capital. Moshe Dayan and Uri Avnery used the same term but did not mean the same thing. It was for me another instance of the importance of not taking things at face value in this conflict.

I’d like to see the statements.

To my mind, the January 1976 draft Security Council resolution needs to be looked at with a similar sceptical eye. I don’t diminish its significance as either a snapshot or a step in a moving picture. But a superficial reading of it, disregarding all the background intrigue, narrow state interests, and inter-state rivalries, carries the danger of seeing what one is inclined to see, or seeing no more than what literally is there, rather than panning out and questioning the broader motives of the supporting parties. In this case, in

particular, of the three Arab states. To put it another way: their apparently unbridled, synchronized support for this resolution ain’t necessarily so.

First, it was not a snapshot; it was part of a long sequence, both for Israel and the US The entire top political echelon in Israel resolutely rejected every opportunity for peace, flatly rejecting any option for a Palestinian state (Rabin forcefully, Herzog hysterically, same with the others). You’re right that there was more behind the 1976 offer. The Arab states kept toning down their proposals, hoping that they could get something the US wouldn’t veto. When they saw that the US was going to veto anything, they stopped trying. Nevertheless, the resolution was quite explicit, as was Israel’s strong and firm rejection, and the support of the Arab confrontation states, in the only form that non-members of the UNSC can express support. As was the PLO’s indirect support in its condemnation of “the tyranny of the veto.”

With the UNSC barred by the US (there was actually another attempt in 1980), UN discussion shifted to the GA, with regular resolutions along similar lines, opposed only by the US-Israel (sometimes joined by a US dependency). Meanwhile, Arab initiatives kept coming, like the Fahd plan, flatly rejected by Israel. That continued until the end of the century. Meanwhile, settlement continued, under Peres’s lead, deep in “Samaria,” with not a hint of change. True, Labor had to abandon its Sinai project, but that’s all. Peres maintained his strong and outspoken rejectionism until he left office, even declaring Jordan to be a Palestinian state in his rejection of the 1988 PLO offer. Rabin never wavered either in word or deed, as exemplified by his support for expanded settlements.

The crucial fact is the significance of this consistent series of events. In the ‘70s, Israel made a fateful decision – eyes open – to choose expansion over security, with terrible consequences, not only for Palestinians but for Israel as well: moral degeneration, increasing international isolation, shift from admired social democratic model to support from the far right as Israel itself shifted to the right, all predicted, all the results of the firm decision in the ‘70s, no nuances.

To your other points. You write: “You draw a distinction between Israel's stand pre-2000 and post-2000. It seems you are suggesting Israel was more flexible after 2000? It's not clear to me how you justify that.”

By the factual record. Until 2000, total rejectionism. In 2000, Barak entertained the notion of a Palestinian state. At Taba, negotiators on both sides claimed that almost all problems were on the verge of resolution when Barak cancelled the meetings. In following years, there were various discussions and offers. So the justification is clear.

You misunderstand my point by calling them “private feelings.” I trust that what I have written above explains my position better.

I think we agree that Arafat and the PLO were on a journey, from total rejection of Israel's existence from the PLO's inception to implicit recognition after 1974 to more explicit recognition from 1988 to open recognition in 2003. But you seem unable to see that Rabin was also on a journey, the final destination of which was still undetermined.

You’re overlooking the crucial difference. The PLO journey is on the record. Rabin’s journey was in what you think was in his mind, belied by everything in public: his statements, his strong support for expanded settlement.

That is a crucial difference.

Arafat himself unquestionably saw that Rabin was on a journey.

He wanted to see that, for his own reasons, which I don’t admire as you know, but that’s a different matter.

I won’t repeat what I have already said in support of the contention but it’s puzzling to me how you clearly see it in one case and fail to see it at all in the other.

Not at all puzzling. In one case we have a definite and explicit record. In the other case, we have beliefs about what Rabin had in mind, which is sharply opposed to what he was saying and doing.

Their respective journeys, in my view, had nothing to do with altruism, international law, or “dovishness” but were propelled by the dynamics set in motion by an irresistible force and an immovable object battling it out. For them (Arafat and Rabin), in contrast with some of their compatriots, the sheer realities were of a higher order than ideological purity. They both were moving towards recognizing the imperative of a deal that would accommodate at least the minimum core aspirations of the other people. A bullet put paid to that, which of course was its intention.

The bullet put paid to the fear by the far right that he was going to offer the Palestinians something, even though he never hinted at a state and was working hard to undermine the prospects with his aggressive settlement programs. Same is happening now with right-wing settler opposition to Netanyahu’s annexation proposals.

Referring to the 1976 draft resolution as a "peace offer of Egypt, Syria, Jordan" is quite a stretch.

Not a stretch. All three supported the peace offer – which it was, explicitly – in the only way that support is possible outside the UNSC.

It is believable in the case of Egypt (proven a year later), credible in the case of Jordan (although, as said, Jordan's enthusiasm for a Palestinian state at that time is doubtful, to say the least), but out of sight in the case of Syria. I am not aware of any other evidence to support the contention that Syria was genuinely serious about reaching peace with Israel or offering peace to Israel at that point of history.

I’m sure all three countries genuinely wanted Israel to disappear. But they also explicitly supported the peace offer and continued to do so when the US forced debate to shift to the GA and as Arab peace plans were put forth.