The Oslo Accords gave political momentum to the principle of a Palestinian state alongside Israel, which European elements had adopted in the 1980 Venice Declarationi. The Accords put a seal of approval on principles that had been taboo in Israel during the period that preceded Oslo: recognition that the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) was the only authorized representative of the Palestinians, discussion of the two-state solution, and an agreed list of the fundamental issues of controversy between the parties which the permanent agreement must address. These frameworks stand to this day, even though they have not led to a formal agreement between the parties. In the context of the creation of this framework, East Jerusalem should be mentioned, since it is the only area of the West Bank that Israel has officially annexed. Furthermore, Israel has invested more material and symbolic resources in East Jerusalem than in any other area of the territories occupied in 1967 and has achieved results accordingly. Almost 40% of the people living in this former Jordanian territory are Israeli citizens, though they are settlers in every sense of the word.

The failure of the parties to reach a permanent agreement moved civil society groups to propose ways to complete the formal political process. The Geneva Initiative [full disclosure: I am one of the leaders of the initiative], a joint Israeli-Palestinian venture, “continued” the discussions on the permanent agreement from the point where the 2001 Taba talks broke off. It provides the parties and international mediators a detailed model of a permanent agreementii. The Geneva Initiative is the only initiative that presents, in great detail and on the basis of research by professionals of both sides, what a permanent agreement might look like. In contrast to other initiatives, which petered out or remained anonymous, the partners of the Geneva Initiative signed their names to the initiative, published it and are still promoting it. The Geneva Initiative became a reference point for public opinion pollsiii, alongside official documents composed during the negotiations on a final agreement, such as the parameters presented by U.S. President Bill Clinton at the end of 2000iv.

In the 21st century the international community updated its positions. United Nations Security Council Resolution 242, which was adopted immediately after the 1967 war and which serves as the basis of all political documents relating to Israel’s relations with its Arab neighbors, including both peace agreements and interim agreements, was at the outset subject to two interpretations regarding the question of which territories Israel was to withdraw from in exchange for peace: a withdrawal from territories or from all the territories it conquered in 1967. Security Council Resolution 2334 of December 2016v put an end to the argument, accepting the position that Israel must withdraw from all the territories conquered in 1967. The resolution also negates the legitimacy of the settlements, including those in East Jerusalem, stating that they constitute a clear violation of international law and have no legal standing and calling for their cessation.

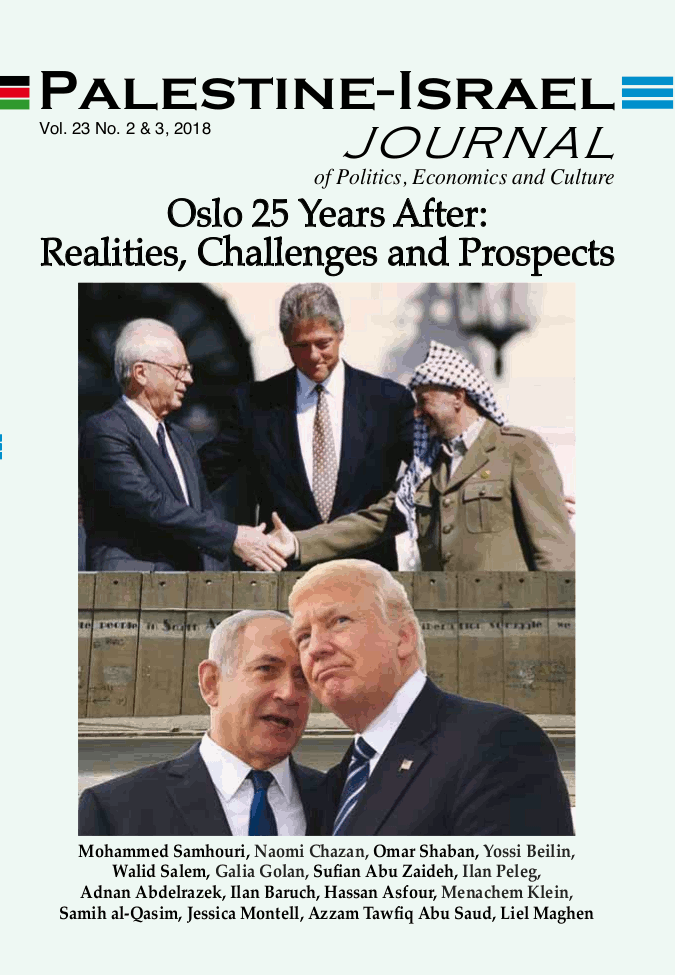

It is important to note that alongside this consensus and repeated warnings that it will soon be impossible to implement a two-state solution, the international political community has not decided on measures that would compel Israel to accept its position. The speech made by former Secretary of State John Kerry in December 2016 exemplifies this gap. In his speech, Kerry not only presented the principles of the agreement he sought to advance — with impressive wall-to-wall support from the international community — but also the gap between the fundamental values of the United States and the international consensus and the reality that Israel had created on the West Bankvi. This gap did not move the U.S. administration to take measures to implement its principles. In December 2017, the Trump administration adopted a sharp change in U.S. policy, but this did not cause any change in the international consensus. The U.S. president recognized Jerusalem as the capital of Israel but had to use the veto in the UN Security Council in order to foil the resolution calling for the cancellation of this recognition. Fourteen of the fifteen members of the Security Council supported the resolution, with only the United States in opposition. In a vote in the General Assembly, 128 states supported the cancellation of the U.S. recognition, 35 abstained and nine opposed itvii.

The Opposition to the Oslo Accordsviii

In the wake of the Oslo Accords and the entrenchment of the Palestinian Authority (PA) in Areas A and Bix, which constitute some 40% of the West Bank, the Israeli opposition to the Accords was forced to give up its demand to annex the entire West Bank. It now demands “only” the annexation of Area C, where the settlements are located, and opposes a Palestinian state in Areas A and B . Its future plans for these territories oscillate between Palestinian local government, which would be dispersed, fragmented administratively and geographically, and under Israeli auspices, and what Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu calls “a state minus,” meaning Palestinian Autonomy over fragmented areas that would have no authority over security, monetary currency or foreign relationsx.

The evacuation of all the settlements in the Gaza Strip in 2005 forced the Israeli right to remove the area from its plans for direct control and settlement. The quantitative gap between a million and a half Palestinians and fewer than 9,000 settlers, in the reality of a difficult intifada, left no other option. The settlements were dismantled, but Israeli control operates at a distance by means of the outer envelope on which the Gaza Strip is completely dependent.

On the level of internal Palestinian relations, the Oslo Accords forced Hamas to choose between the civil war that would break out should it refuse in principle to accept the rule of the PA and coming to terms with the PA’s existence and accepting its authority. In the 1990s, Hamas chose the second option, both out of the desire to avoid a civil war like that in Algeria in the 1980s and because the Oslo Accords enjoyed wide support among the Palestinian public. Hamas, however, was not ready to participate in the first elections to the Legislative Council in 1996. In the 1990s and even more so after 2000, Hamas strengthened its political profile. It participated in the elections for the Palestinian Legislative Council in 2006 and won, having based its campaign on a political platform substantially different from the Islamic Covenant, the organization’s founding document published in 1988.

During the middle of the second decade of the 21st century, Hamas gave the PLO a green light to negotiate for a state based on the June 4, 1967 borders and to allow the results to be decided in a public referendum. In 2017, Hamas published “The Document of Principles and Policy,” which essentially replaces the Islamic Covenant as the guidelines of the movement. This is a compromise document between the pragmatic stream of the Hamas leadership, which called for accelerating the politicization of the movement, and the more conservative elements. The document refuses to grant legitimacy to the Oslo Accords but, at the same time, announces the organization’s transition from an Islamic movement to a national-religious liberation movement and its readiness to mobilize for the establishment of a Palestinian state in the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem which would not recognize Israelxi.

With no coordination between them, since 1993 the groups opposed to the Oslo Accords in Israel and the PA have placed the Temple Mount at the center of the conflict. This should not be seen as a mere tactical step to enlist mass support but, first and foremost, as a result of what is written in the Oslo Accords themselves: The Accords, for the first time, placed Jerusalem on the negotiating table, and the Camp David Summit of 2000 dealt primarily with this issuexii. The question of sovereignty over the Temple Mount and the Israeli demand to allow Jewish prayer at the site stood at the heart of the controversy between the delegations and was the main reason that an agreement was not reached. This was followed by Ariel Sharon’s visit to the Temple Mount and the controversy surrounding it, which ignited the so-called Al-Aqsa Intifadaxiii.

The Reality on the Ground

In the 1990s, the Oslo Accords legally and politically divided the 1967 territories into three categories in terms of the degree of control of the PA and its powers. To these must be added East Jerusalem, which Israel immediately annexed at the end of the June 1967 war. In the 2000s, Israel created a more complicated reality. The construction of the Separation Barrier, 2003-2005, brought about the creation of an additional category of territory located between the Green Line and the barrier (the “seam” area). Palestinians are allowed to be in this area only with a permit from the military commander; from this perspective, it is similar to the territories of the sovereign State of Israel, which residents of the West Bank are allowed to enter only with a special permit.

To this legal-geographic-administrative reality we must add the regulations Israel imposed in 2007 which separate, from an administrative point of view, the residents of the Gaza Strip from those of the West Bank — despite the fact that the Oslo Accords of September 1993 stated that the two areas constituted one unitxiv. To sum up, during the Oslo years the Palestinian population was divided into five categories: those under the rule of the PA in Areas A and B; the Palestinians in Area C, under direct Israeli control; those requiring Israeli permits in order to reside in the area between the Separation Barrier and the Green Line; East Jerusalem residents; and residents of the Gaza Strip. The humanitarian situation of the Gaza residents is particularly difficult; according to UN reports, Gaza will be unfit for human habitation even before 2020xv.

The increase in the number of settlers during the Oslo period further complicates the reality on the ground. In 1994, there were some 128,000 settlers in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, in addition to some 170,000 settlers in East Jerusalem. In 2016, there were some 400,000 settlers in the West Bank, not including East Jerusalem, whose numbers in 2014 reached some 316,000xvi.

The settlers “bring” Israeli law with them to the territories of the West Bank, and it applies to them in the broad legal areas of the local and regional councils. In addition to the settlers, military, police, and intelligence forces are dispersed throughout area, and their numbers are estimated at tens of thousands. Israelis who live and serve in the West Bank enjoy a system of roads, some of which are for their exclusive use. Officially, Area C is administered as an occupied territory by the head of the army’s Central Command, but in fact Israeli law and Israeli citizens constitute a strong presence, and this has major significancexvii. At the end of 2017 and the beginning of 2018, the government initiated measures that would link the settlements directly to the Israeli legal system, essentially bypassing the “intermediate station” of the Head of Central Commandxviii. In essence, the Green Line, which distinguishes between Israel and the West Bank, has been erased. It should be noted that as Israelis move east of the Green Line, the “West Bank” (a borrowed term) moves west. Palestinian citizens of Israel, mostly the young and educated, identify as Palestinians and not as Israeli Arabs. The clashes of the intifada of the year 2000 spread to Israel’s mixed Jewish-Arab cities, and groups of national-religious Jews, who in the past moved to the settlements, are now moving to these cities with the aim of “Judaizing” them.

Summary

From all of the above it emerges that the Oslo Accords created a framework comprised of many parts, each of which contains a structural contradiction. The Accords started out as interim agreements, and parts of them have become irrelevant and have not been preserved. The Accords did not lead to a permanent agreement: Instead of paving the way for clear separation into two states, they created a system of brutal Israeli control which falls on the PA. At the same time, both Israel and the PA deny this and act to stretch a distinct line between the two parts of this system. In the political arena, the gap between Israel and the international consensus has grown, but this consensus has not compelled Israel to take any steps. Those in opposition to Oslo have unwillingly and partially come to terms with the reality on the ground and, at the same time, work to undermine it: Israelis by means of massive settlement activity and the creation of a binational reality, and Palestinians by maintaining the split between the Gaza Strip and the West Bank.

On the ground, ethnic-horizontal lines of separation and vertical lines of separation exist simultaneously. The ethnic-horizontal lines of separation are expressed in the reality of a single regime between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, in which Jews enjoy superiority over the other half of the population, the Palestinians. The ethnic lines of separation separate not only Jewish citizens of Israel and Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza Strip but also Jews and Palestinians in Jerusalem and Jewish citizens of Israel and Arab-Palestinian citizens of Israel within the sovereign State of Israel. During the Oslo period, the ethnic lines of separation in the West Bank were emphasized, and since 2000 they have acted to heighten the ethnic divide between Jewish and Palestinian citizens of Israel. At the same time, there are legal, political, and military lines which vertically differentiate between areas where Israeli citizens live, including Arab-Palestinian citizens, and between the Palestinians living in the 1967 territories.

In the years since the signing of the Oslo Accords, a race has developed between Israel and the PA. Israel acts on the ground, in the ways described above, to strengthen its control while exploiting its superiority. The PA does not challenge Israel; on the contrary, it cooperates with Israel on security and civilian matters. Officials of the PA have internalized their inferior position and dependence on Israelxix. Headed by Mahmoud Abbas, the PA acts on the political level to create international pressure to push Israel to agree to parameters for a permanent agreement, which so far no Israeli government has been willing to accept. As we saw above, there have been a few achievements in this area, but they have been hampered by the failure of the PA to enlist the U.S. as an ally, even in the Obama era. The gaps between the Palestinians and the U.S. administration have significantly deepened and widened under President Donald Trump. The president has announced that Jerusalem is the capital of Israel, that the question of Jerusalem is longer on the agenda, and that if the Palestinians refuse to return to the negotiating table he will halt the U.S. financial aid to the PA. In response, the Palestinians announced that they are sticking to their position that the U.S. will no longer be able to serve as a mediator between them and Israel.

To date, these contradictions have not led to the collapse of the framework created by the Oslo Accords. It can be assumed that the framework is holding up precisely because of its complexity and fragility. At present, it is impossible to know what will lead to its internal collapse or to identify the weak link in the framework whose collapse, under pressure, will cause a domino effect. These are open questions and the possibility of their occurring must be considered, particularly in light of the break between the Palestinians and the Trump administration. Another question is whether the Oslo framework will be able regain strength and recover. In my opinion this is possible, but it is difficult to anticipate that the return to the path of an Israeli-Palestinian agreement – whether partial agreements in stages or a comprehensive permanent agreement — will be easy, in the reality described above. Any strengthening of one of the elements of the framework at the expense of the others — for example, the strengthening of Israeli control, or replacing the regime of Jewish privileges with a more egalitarian regime, whether in the form of two states alongside each other, with or without confederation, or in the form of one state — will arouse opposition on the part of those hurt by it. And those who will be hurt are those who currently enjoy a privileged position, economic benefits and resources. At present, however, the leaderships prefer to maintain it, to gain in the short term, and to raise the price of change in the future, when change becomes inevitable.

Endnotes

iThe text of the Oslo Accords, officially the Declaration of Principles, can be found at: http://www.mfa.gov.il/mfa/foreignpolicy/peace/guide/pages/declaration%20 of%20principles.aspx

iihttp://www.geneva-accord.org/mainmenu/english

iiiLike for example the joint public opinion surveys carried out since 1993 by the Palestinian Center for Policy and Survey Research run by Dr. Khalil Shikaki with first the Truman Center at the Hebrew University and now the Tami Steinmetz Center for Peace Research at Tel Aviv University. http://www.pcpsr.org/en/node/717

ivFor the Clinton Parameters and the Israeli and Palestinian responses see: https:// en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Clinton_Parameters

vhttp://www.un.org/webcast/pdfs/SRES2334-2016.pdf

vihttps://2009-2017.state.gov/secretary/remarks/2016/12/266119.htm

viihttps://www.un.org/press/en/2017/ga11995.doc.htm

viiiMy use of the term opposition to the Oslo Accords refers here also to political forces that may be in control of the government in Israel and may divide control of government in the PA with those who support the agreements.

ixSee for example plan by Naftali Bennett https://www.jpost.com/Magazine/Adiplomatic- Right-Education-Minister-Naftali-Bennett-pushes-right-506960

xhttps://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/netanyahu-i-m-willing-to-give-palestinians-astate- minus-1.5488898

xiMenachem Klein, “Competing Brothers: The Web of Hamas-PLO Relations”, in Terrorism and Political Violence, Vol.8 No. 2 (Summer 1996), pp. 111-132; Menachem Klein, “Hamas in Power”, Middle East Journal, Vol. 61 No. 3 (Summer 2007), pp. 442-459. The document of principles and policy can be found in English translation at: http:// www.middleeasteye.net/news/hamas-charter-1637794876

xiiMenachem Klein, The Jerusalem Problem, The Struggle for Permanent Status, Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2003, pp. 63-110

xiiiKlein, Shem, Laharis, Negotiations on Jerusalem: A study of the Israeli-Palestinian negotiating processes on the topic of Jerusalem, 1992-2011, Jerusalem, The Jerusalem Institute for Israeli Research, 2011 (in Hebrew).

xivBtselem, Illegal in own homes, September, 2008 http//www.btselem.org/Hebrew/ press_releases/20080910

xvAmira Hass, https://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/palestinians/.premium-asgaza- situation-deteriorates-un-hangs-hopes-on-private-sector-1.5433549

xviStatistics from Peace Now, http://peacenow.org.il/settlements-watch/matzav/ population; Menachem Klein, Doves is the skies of Jerusalem: The Peace Process in the city 1977-1999 (The Jerusalem Institute for Israeli Research 1999) pp. 11; Jerusalem Statistical Annual 2016; There is a difficulty to survey some of the sections of East Jerusalem, in order to arrive at an exact figure for the Palestinian residents of the city.

xviiA clear illustration of the new reality in the West Bank can be seen from the refusal of the government in 2017 to allow the Kalkiliya Municipality to expand in Area C and to gradually build 14,000 new housing units. Kalkiliya’s area is 4 square kilometers, where 53,000 people live. The refusal of the political echelon is determined by settler pressure, despite the recommendations of the IDF and the Security Services. See Aron Heller and Muhammed Daraghameh, “Expansion Plan Highlights: Crowded West Bank City’s Plight”, Associated Press, July 12, 2017.

xviiiFor example, the Minister of Education initiated a law that would place the academic institutions in the settlements under the authority of the Council for Higher Education instead of under the authority of the Council for Higher Education in Judea and Samaria, and the Minister of Justice determined that every government law will include suggestions about how it can be carried out immediately in the settlements. https://www.haaretz.co.il/news/politics/1.558593.

xixAmira Hass, Bureaucracy captures the Palestinian Liberation Organization, Haaretz, January 19, 2018 (in Hebrew).

This article is adapted from a chapter titled “The Endurance of the Fragile Oslo Accords” that will be published in Hebrew in Oslo Process, A Milestone in the Historical Trials to Solve the Israeli – Palestinian Conflict, edited by Ephraim Lavi, Yael Ronen and Henri Fishman, Tel Aviv University Tami Steinmetz Center for Peace Studies, forthcoming 2018.