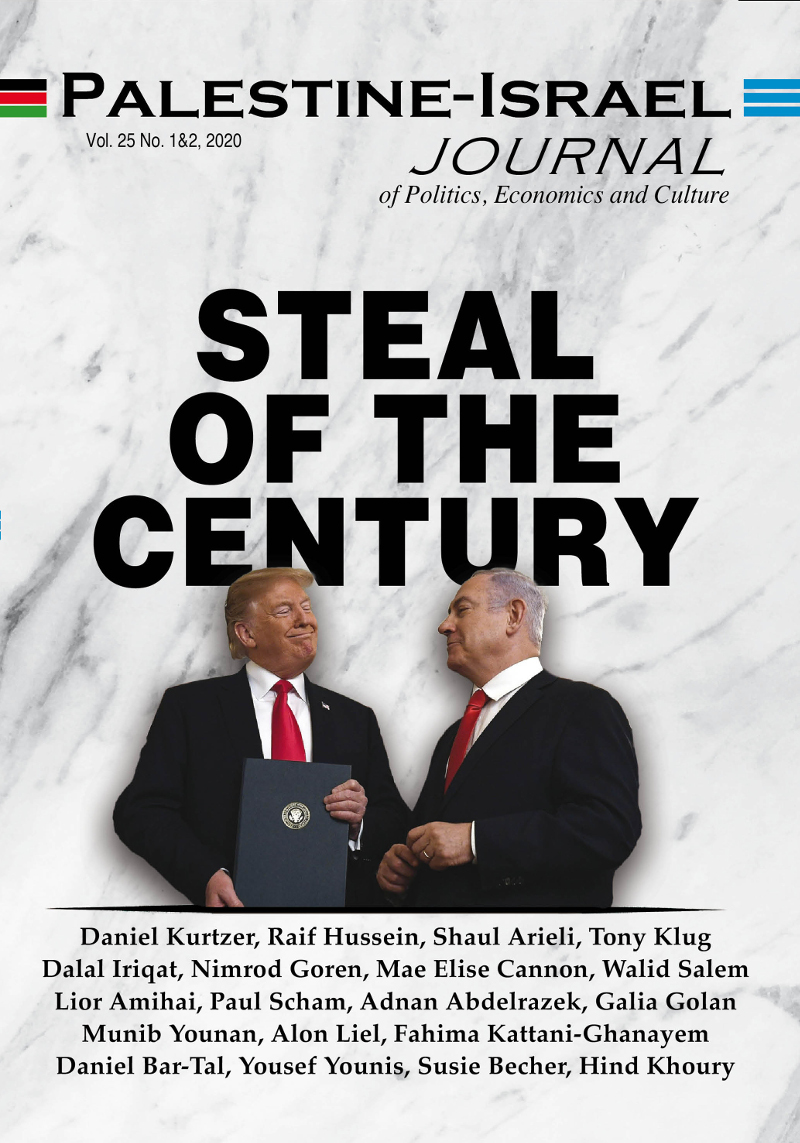

It took 71 years for the Palestinian national movement to join the international community by recognizing the latter’s decisions. It took Israel 15 years to accept the United Nations’ decisions as a basis for a resolution of the conflict with the Palestinians. Yet it took only four years for the Israeli government, headed by Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu and with the backing of U.S. President Donald J. Trump, to backtrack from this. The “Deal of the Century” sets the conflict back 100 years.

The Balfour Declaration of 1917 and the British Mandate in 1922 — which called for the establishment of a Jewish homeland — produced the Palestinian policy of seeking to correct the historical injustice done to them by the fact that “the principle of self-determination was not applied to Palestine at the time that the Mandate was created in 1922 because of the aspiration to enable the establishment of a Jewish homeland,” as was written in the report of the UN Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) in 1947. For 71 years, the Palestinians rejected all UN decisions which recognized Israel and prevented them from establishing one Palestine from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea, beginning with the Peel Commission in 1937, via the White Paper of 1939, UN General Assembly Resolution 181 (the Partition Plan) and UNGA Resolution 194 on the issue of refugees. This policy, which was accompanied by military and terrorist attacks against Israel, proved disastrous for them, leading to the Nakba (catastrophe), the lack of a state, and the continued wandering of the Palestinian leadership from Israel to Egypt, to Jordan, to Lebanon, and to Tunis.

The Historic Change in the Palestinian Position

A number of factors — the peace between Israel and Egypt, the collapse of the Soviet Union, the First Intifada, the growth of an alternative internal leadership, the emergence of Hamas as an opposition party, and more — brought about a change, and in 1988, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) for the first-time recognized Resolution 181, which meant recognition of the division of the land and a state for the Jewish people, and United Nations Security Council Resolution 242, which meant that the state of Palestine “… does not include more than 22 percent of historic Palestine.” In other words, the Palestinian state would include the West Bank and the Gaza Strip and its capital would be in East Jerusalem, and there would be an agreed solution to the refugee problem in the spirit of the commitment Salah Khalaf (Abu Iyad), Yasser Arafat’s political deputy, made to the Americans in his 1988 “15 Points” letter that “the right of return cannot be realized through hurting Israel’s interest” and should not “become an obstacle which cannot be bridged over.”

The Evolving Israeli Position

Israel entered into the Oslo Process in 1993 with a different approach. In a speech to the Knesset on October 4, 1995, Yitzhak Rabin presented his view that “…we see the permanent solution in the framework of the area of the state of Israel, which will include most of the area of the land of Israel … and alongside it a Palestinian entity which will include most of the Palestinian residents who are living in the Gaza Strip and the West Bank. We want this to be an entity which is less than a state … the borders of the state of Israel, at the time of the permanent solution, will be beyond the existing the lines before the Six Day War.”

Ehud Barak, the first to begin negotiations on a permanent arrangement, saw it in a similar fashion. He thought the goal of the negotiations was “a just division of the area of Judea and Samaria” as quoted in Danny Yatom’s 2009 book “Shutaf Sod” (Access to Secrets). At the Camp David Summit in 2000, he proposed that “an area of no less than 11 percent, where 80 percent of settlers live, will be annexed to Israel, and in addition we will not transfer sovereign Israeli territory (land swap) … and for a number of years, Israel will rule over one quarter of the Jordan Valley, in order to guarantee control over the crossings between Jordan and Palestine.” Concerning Jerusalem, he proposed that “the external Muslim neighborhoods will be transferred to Palestinian sovereignty (the 22 villages that Israel annexed in 1967), and the internal Muslim areas will remain within Israeli sovereignty (the original East Jerusalem).” He also insisted that “the Temple Mount will be under Israeli sovereignty ... with some form of Palestinian guardianship

and permits for Jews to pray on the Mount.” After the publication of the Clinton Parameters in 2000, Barak took another step forward in 2001, but he still insisted on annexation of 6-8% of the West Bank without anything in exchange.

Olmert and Abbas — Maximum Degree of Agreement

The first to arrive at a maximum degree of agreement in the framework of negotiations was Ehud Olmert during the Annapolis Process in 2008, 15 years after mutual recognition between Israel and the PLO. Similar to the PLO’s decision to recognize UNSCR 242, this was not the product of an honest recognition of the Palestinian right but rather a sober view of the possible within the existing reality. In an interview with Ma’ariv in 2012, he explained: “Of course, if I could live in the entire area of the land of Israel, and also live in peace with our neighbors, and also preserve the Jewish character of Israel, and also preserve it as a democratic state, and also be able to gain the backing of the international community — I would do so. But this is impossible, and when something is impossible, responsible leadership is required to recognize this, to reconcile with it, and to draw the necessary conclusions, to give up on cheap populist policy and to act with responsibility and seriousness rather than to seek quick and easy popularity.”

With the mediation of U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, the sides agreed on the following parameters:

Borders: the 1967 lines as a basis (with land swaps based on a 1:1 ratio).

Security: demilitarization of the Palestinian state and widespread security measures;

Jerusalem: a division of Jerusalem into two capitals without changing the status quo of the holy sites;

Refugees: a solution to the refugee problem in its entirety via return to the Palestinian state, compensation, and the return of up to 100,000 refugees to Israel.

Based upon the aforementioned parameters, the Palestinian proposal, which today is not mentioned at all in Israeli discourse, was a land swap of 1.9%, which would enable 63 percent of the Israelis living on the other side of the Green Line to remain (an additional proposal without a map would have enabled 75% of the Israelis to remain), as well as annexation of the Jewish neighborhoods, except for Har Homa, and also the Western Wall, the Jewish Quarter, half of the Armenian Quarter and what remains of Mount Zion. The Israeli proposal was a 6.5% land swap, with 85% of the Israeli settlers remaining; demilitarization of the Palestinian state; annexation of all Jewish neighborhoods in Jerusalem, in addition to Arab Beit Safafa; a special regime in the Historic Basin; and a return of 5,000 refugees and compensation.

Regarding the gaps between the two, Olmert said in 2012: “I was within reach of a peace agreement. The Palestinians never rejected the proposals, and even if for the thousandth time there will be those who will try to claim they rejected the proposal, the reality was otherwise. They did not accept them, and there is a difference. They didn’t accept because the negotiations had not concluded; they were on the verge of concluding. If I had remained prime minister for another four months to half a year, I believe it would

have been possible to reach a peace agreement. The gaps were very small. We had already reached the last lap.”

No Netanyahu Map

Netanyahu began his second term with the famous Bar-Ilan speech in 2009 — a speech which only a few, beginning with his father Benzion Netanyahu, really understood. Speaking on Channel 2 TV in July 2008, the latter said: “Benjamin doesn’t support a Palestinian state, only with conditions that the Arabs will never accept. I heard that from him.” Netanyahu chose to ignore the entire process and all the changes described above and stuck to his position from his 1993 book, A Place Among the Nations, which stated that “the conflict is not about particular territories of the land, but rather about the entire land. The conflict is not territorial but existential. The subject at hand isn’t where will the border pass, will it be this or that route, but rather the Israeli national existence. They do not want a Palestinian state alongside Israel, but rather a state in place of Israel.” It is not surprising that Netanyahu never presented a map or plan to U.S. President Barack Obama and his advisors. His position was worlds apart from the parameters that were presented at Annapolis. Trump, Jared Kushner and David M. Friedman were the petri dish for his approach, which was crystallized together with the messianic nationalist right headed by Naftali Bennett and Ayelet Shaked. The American team went with this and published the proposal.

The Trump Plan — A Mortal Blow

Despite the choice of the headline “two-state solution,” the Trump proposal first and foremost deals a mortal blow to everything achieved to date. It sets back the Israeli policy discourse by 15 years, reviving the illusion of an agreement without any concession on the West Bank, and it may set back the Palestinian discourse by a hundred years to the notion of one state with an Arab majority (even before the return of refugees.)

Second, the details of the proposal, which are so fundamentally different from the Annapolis paradigm, make cynical use of concepts that have characterized the peace discourse since Netanyahu’s rise to power in 2009 — two states, land swaps, demilitarization, Palestinian capital and more — and attest to professional ignorance in the areas of security, geography and law. The Palestinian state which is being proposed is a series of enclaves with no territorial continuity and no external borders, turning it into one big enclave with a border stretching to almost 1,500 kilometers, more than one and a half times the length of the current borders of Israel. Within this enclave will be 15 Israeli enclaves (settlements), and within Israel there will be 54 Palestinian enclaves (villages).

International experience teaches us that except for the Netherlands and Belgium, enclaves are not a realistic solution between sides that have a history of violence between them. The IDF would become an army of defense of the enclaves. The winding border would make it impossible to maintain a separate economic system and to enable the Palestinians to be detached from the system that limits them today. Half of the lands that would be annexed to Israel are private Palestinian property which would require broad functional arrangements beyond the capacity of Israel. The proposed Palestinian capital in the neighborhoods on the other side of the Separation Wall in Jerusalem is not in any way suitable for such a purpose. The construction in those neighborhoods has gone on without a formal planning process. It lacks infrastructure and public institutions and is not located on central economic and transportation arteries.

Withdraw the “Deal of the Century”

The “Deal of the Century” must be shelved and must disappear. It does not and will not have a Palestinian partner. The reactions from the international community indicate that it does not contain the possibility of justification of any Israeli annexation. Its great damage to Israel is not from the possibility of its realization but rather its implications. The plan proposes to legitimize the existing situation in which two different legal systems exist in the same area on the basis of ethnic criteria and to add to it annexation, which will be defined as apartheid. It deals a mortal blow to the PLO, which has tried since 1988 to lead a political discourse based upon a resolution of the conflict instead of an “armed struggle.” It will push the Palestinian Authority toward ending its security cooperation with Israel. It is a blow to the value of citizenship, given the proposal to transfer Arab citizens of the state to Palestine. It is a blow to the rule of law and the right to property by legalizing the illegal outposts which were built on stolen Palestinian land. It will encourage the movement of Palestinians from the neighborhoods outside of the Separation Wall into the city of Jerusalem itself. And it will hasten the exit of Jews and will change the demographic balance which has existed for the past 52 years.

And in the end, whoever seeks to see the Trump proposal as a legitimization of annexation will discover that such a unilateral act by Israel will lead eventually to annexation of the entire West Bank, to an ongoing military and political confrontation, to a totally torn and divided Israeli society, and to a harsh blow to its economy. A wake-up call is necessary and inevitable.

A Hebrew version of this article appeared in Haaretz under the title “15 Years After” in the print edition and “The Trump Plan sets the Israeli-Palestinian conflict back by dozens of years” in the online edition.