Since the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, fundamental developments have taken place in the social and economic policy of the state as well as in its policies toward the Arab world, the Palestinian people and their cause, and primarily the Palestinian minority within its boundaries. In the latter case, we have witnessed a profound change in the government’s view of the nature of the relationship of the state to its “Arab citizens,” i.e., the Palestinian minority.

In order to facilitate a better understanding of the state of Israel and its policies and to trace the developments in Israel over the past seven decades, I have divided the developments into three eras:

First Israel 1948-1977

Stage one: Creation of the “New Jew” 1948-1966

Stage two: Occupation and challenging the Palestinian identity 1967-1977

Second Israel 1978-2005

Stage one: War against the PLO and the unity of the Palestinian people 1977 - 1991

Stage two: Preserving the privileges or the end of the stage of the “New Jew” 1992 - 2000

Third Israel 2006 to the present

Stage one: Military change of course 2006-2008

Stage two: Planning for the major transformation and laying the foundations for the new Zionism 2009-2012

Stage three: Netanyahuism (New Zionism) 2012–present

In each of these eras, qualitative social changes, prominent economic transformations and changes to central political strategies took place, leaving clear fingerprints on the social and political structure and on Israel’s engagement with its Palestinian minority.

These immense and central transformations are seldom taken into consideration in political interaction or scientific research engagement with Israel and are usually not given the space, status and attention they deserve in order to be tackled objectively and realistically.

Taking an objective approach means recognizing that Israel has undergone radical changes and no longer resembles what it once was — neither its political elite, nor its strategies, nor the composition of its society, nor its self-perception. This approach would open new horizons for politicians to develop realistic strategies and sophisticated tactics to deal with these changes that have swept Israel, its political system and its social order.1

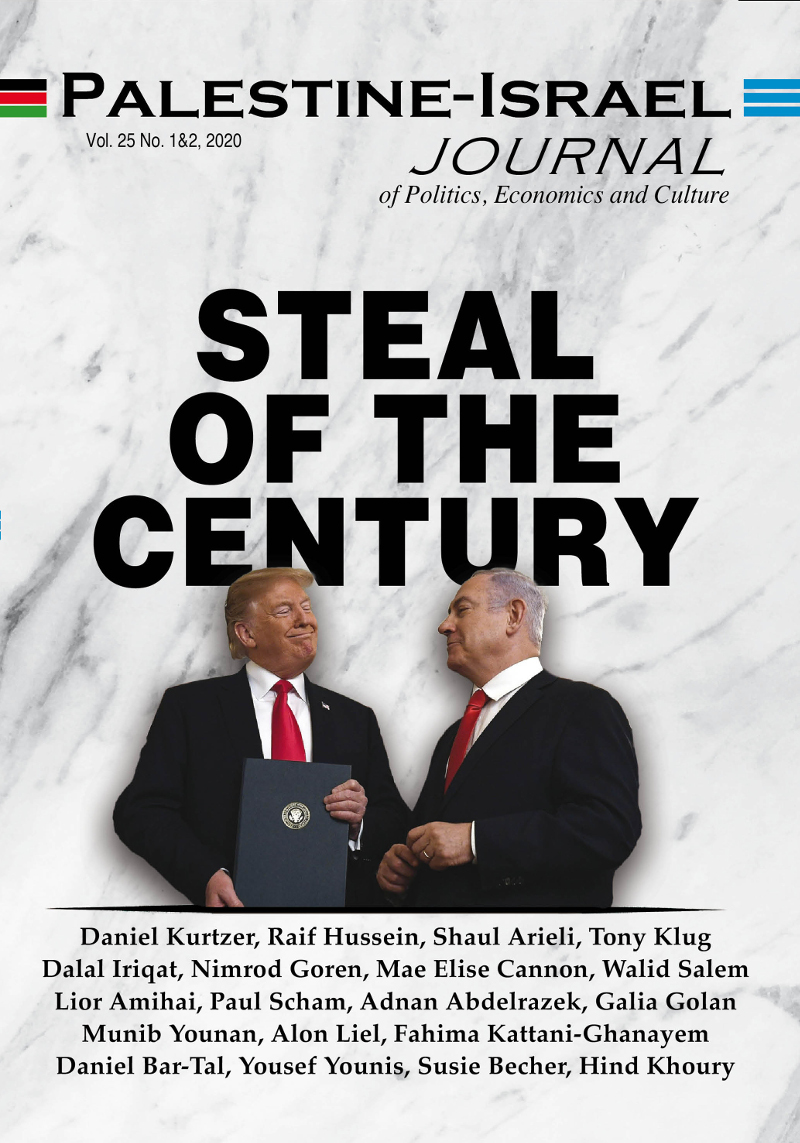

The New Zionist ideology, which I call “Netanyahuism,” was founded by Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu. It is based on a new vision of Israel’s position in the Middle East, its self-image, the Palestinian issue, and the future of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. It rests on new constants that modify Zionist ideology to conform to the changes that have swept Israel, the Middle East, and the world order.

The most important of these constants are:

- Replacement of the land-for-peace equation with the economy-for-peace equation based on normalization.

- No Palestinian sovereignty over the territories occupied in 1967 or in East Jerusalem.

- International law and international resolutions, including support for the two-state solution, impede resolution of the conflict and Israel’s integration into the Middle East.

- The issue of the Jewish refugees from Arab countries is on a par with the issue of the Palestinian refugees.

- The demographic dimension and national allegiance of the Palestinian minority in Israel pose a threat to the Jewishness of the state and, therefore, their political rights must be linked to loyalty to the state.

- Recognition of the Jewishness of Israel is an essential condition for its relationships with its neighbors as well as its international relations.

- Leveraging official and public campaigns against anti-Semitism around the world in support of New Zionism by equating any opposition to the New Zionism with anti-Semitism. And, since Netanyahuism denies the national rights of the Palestinian people, any claim to these rights becomes a form of anti-Semitism.

Netanyahuism requires the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the political elite of the Palestinian minority in Israel to adopt a new strategy that takes into account the ideological and political developments in Israel, the major upheavals in the region, and the end of unipolarity in the global political order.

Israeli Policies Toward the Palestinian Minority

The Zionist Movement’s strategy toward the country’s indigenous people and the systematic ethnic cleansing in historical Palestine were clearly defined before the establishment of Israel. Israel Zangwill, one of the major ideologists in the Zionist Movement, said: “Either we have to expel the human beings and clans on the ground by force of the sword, as our ancestors did in the past, or there will be a continuous confrontation coupled with a complicated problem through the presence of strange and large ethnic groups here and among us.”2

The idea of transfer of the indigenous people was also put forward in Theodor Herzl’s memoirs, along with plans for its implementation.3 David Ben-Gurion held this view as well, as seen in his remarks following the announcement of the 1947 Partition Plan: “In the event of a military confrontation with the other party, we will consider the remaining Arabs, whom we see as illegal aliens within our borders, as agents that can be deported outside the borders of the Jewish state…”4

The First Israel did not have a clear strategy for dealing with the indigenous people who remained on their land and, therefore, put them under military rule until 1966 and robbed them of their basic human rights. Fearing a global backlash that would impede recognition of the new state, the First Israel later granted them the right to vote in Knesset elections. From the very beginning, Israel viewed the indigenous people as religious and ethnic minorities and defined them in official records as Muslims, Christians, Druze, Bedouins and Circassians. From the First Israel to the present, the Israeli political establishment has used the term “Arabs” as a collective nickname, refusing to recognize the Palestinian national identity of the indigenous people of the country. Former Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir is not the only one who denied the existence of the Palestinian people.5 On his visit to Austria in 1997, Netanyahu reiterated what Meir said, adding that the majority of the “Arabs have come from the neighboring countries to look for jobs in the workplaces created by the Jews here.”6

The notion of redrawing the borders to exclude the Triangle communities presented in the “Deal of the Century” must be understood in the context of Netanyahuism’s goal of revoking the citizenship of the indigenous people and reducing their status to that of residents. Palestinians in Israel have had the right to vote in Knesset elections since 1949, but voter turnout has varied. The right to vote in itself does not necessarily mean that they have much influence on Israeli domestic and foreign policy. The Rabin government had to rely on the Democratic Front for Peace and Equality and the Arab Democratic Party to obtain a parliamentary majority for the Oslo Accords, but the support of the Palestinian minority did not yield any tangible gains in return.

Since the founding of the state of Israel and the Nakba (catastrophe), the struggle of the Palestinian minority has centered on the demand for social equality in the face of the state’s attempts to obliterate the Palestinian national identity and place a wedge between the Palestinians inside and outside the country in order to fracture its demographic majority. This policy can be seen in the First Israel’s settlement of the Negev Bedouins, in Ariel Sharon’s 1998 “Seven Stars” plan for the Triangle, and the campaign to “Judaize” the Galilee. The policy ultimately failed for several reasons, the most important of which are:

- The presence of a Palestinian national elite within their political parties and civil society institutions. This influential and balanced minority clung to its patriotic and national identity and resisted dissolution and integration strategies.

- The creation of awareness that distinguishing between the dominant Jewish majority and the Palestinian minority by limiting the latter’s development and growth and systematically excluding them from jobs and positions in state institutions constitutes outright discrimination. Violent confrontations between Palestinians and the Israeli security authorities, such as the Land Day events in 1976, and clashes with Jewish racists that have escalated since the second intifada in 2000.

- The emergence and expansion of the Islamic movement, which has strengthened the Palestinian minority.

Since the beginning of the second stage of the Second Israel, there have been fundamental demographic and ideological changes within Israel that have pushed the Palestinian minority to increase its internal cohesion, adhere to its national identity, and take the offensive in its demands for social equality and civil rights.

This stage witnessed the signing of the Oslo Accords and letters of mutual recognition between Israel and the PLO, which split Israeli society into a weak group that supported a settlement with the Palestinians and a strong group that opposed it. The climax of this schism within the Jewish community was the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin, the beginning of the slow disintegration of the Labor party, and the veritable extinction of the peace camp and the Palestinian minority’s loss of its strategic Jewish ally, which it believed was necessary to achieve its social demands within the state of Israel.

Among the most important changes in the Israeli political and social reality at this juncture were:

- The arrival of more than a million Russians immigrants and their social positioning and competition with the Palestinians in many areas of life, followed by their establishment of political frameworks with a racist view of the Palestinian minority.

- A marked increase in the number of Palestinian academics and in public displays of pride in the Palestinian national identity after the Israeli security establishment lifted the ban on using Palestinian national symbols, such as the flag, after signing the Oslo Accords.

- The establishment of the Balad party and its proposal for a new citizenship relationship according to which “Israel is the state of its citizens” instead of the Zionist equation that “Israel is a Jewish state.”

- Rabin's assassination at the hands of a Jewish extremist and the role of various Jewish personalities and political and religious movements, including the Likud, in creating the atmosphere that led to it.

The violent response of the Israeli security services to the demonstrations of the Palestinian minority in solidarity with the Palestinians in the occupied territories following the failure of the Camp David Summit, in which the security services killed 13 Palestinian citizens of Israel.

Increased awareness of the Palestinian national identity, especially among the youth, in response to the rise in racism within the Jewish political establishment and the public, as seen through the enactment of racist laws and attacks on Palestinian citizens and their property,7 was not met by a marked change in the policy of the Palestinian parties regarding their strategic orientation toward the state and its institutions and the relationship of the Palestinian minority to the Jewish community. The Palestinian political elite remained fragmented and content with some minor privileges they secured for their public from the ruling Zionist establishment. Palestinian institutions such as the High Follow-Up Committee remained hostage to the abominable clan system and did nothing to democratize or develop a new strategy to confront the changes that had taken place and those to come in the transition to the Third Israel.

Creation of the Joint List

When the electoral threshold was raised to 3.25% prior to the 2015 elections, the Palestinian parties were forced to run as an alliance and established the Joint List. This alliance was not the result of the development of a unitary consciousness to confront rising Jewish racism; it was a “marriage of convenience” designed to help the parties cross the electoral threshold.

The Joint List has not yet developed a strategy to meet the latest challenges, most important of which is the Nation-State Law, and has stuck to its old strategy of demanding social equality. Its political program has remained hostage to the Israeli Communist Party, the largest and most powerful party among its components. The fact that it considers itself the only party that can cross the electoral threshold alone gives it the clout to pressure the others not to deviate from the strategy it devised in the 1950s and to block the circulation of new ideas that do not conform with Leninist ideology.

Public pressure on the Joint List to change this strategy has increased since the enactment of the Nation-State Law, which enshrines Jewish hegemony at the expense of the country’s indigenous people; the exploitation of the rise in anti-Semitism in the West to squelch criticism of Israel’s policies; the increase in racism within Israeli society; and with the delegitimization of the Palestinian parties and Palestinian national symbols. The demand for social equality now looks like a utopian dream. The “Deal of the Century’s” plans for the Palestinians in the Triangle area helped the Joint List realize that the Palestinians’ social and political status in the Third Israel is tenuous at best. The Palestinians are seen as temporary guests, subject to the colonial rule of “divide and conquer.”

The First and Second Israels were largely able to conceal racial discrimination through diplomacy and political acumen, although the enactment of the Nakba Law, which prohibits public commemoration of the Nakba, was a sign of things to come. Discrimination has since become a political and social reality that is anchored in legislation and enjoys a large political and social consensus. The Knesset elections in October 2019 produced 94 right and extreme right parliamentarians who supported various laws that discriminate against non-Jews; underscore the superiority of the Jewish majority; and limit the political, social and economic development of the Palestinian minority, restrict their freedom of expression and seek to purge modern Palestinian history from their educational curricula.

The “Deal of the Century,” especially its plan for the Triangle area, was for the greater part expected, not only because of successive racist statements about the “demographic time bomb” but also because of previous Israeli attempts to change the identity of the region. Now, following the release of the plan which embodies the spirit of Netanyahuism, the Palestinian political elites must draw up a new strategy to confront the New Zionism. The demand for social equality is no longer enough in the face of the racist onslaught and a governmental system that is gradually transforming into a system of apartheid, as seen by former Israeli Ambassador to South Africa Alon Liel.8

A Strategy of Resilience should be based on two main principles

The strategy of resilience in the face of the “Deal of the Century” and of challenging moves to marginalize the indigenous people should be based on two main principles:

- Democratization of the main representation institutions of the Palestinians inside Israel, above all the High Follow-Up Committee. The full strategy for this was developed in May 2019 and was published by Arab news sites and newspapers inside Israel.9

- Internationalization of the issue of the Palestinian minority in Israel by referencing internationally recognized laws and norms, most important of which is the European Law for the Protection of Minorities10 and Article 27 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.11

This strategy for the Palestinian minority in Israel will be an interim plan that must be coordinated with the future strategy of the PLO for the Palestinian people in the territories occupied in 1967 and for Palestinians abroad. It should be implemented in phases as follows:

- Internationalize the issue of the Palestinian minority in Israel through international institutions by demanding their recognition as a national ethnic minority. This step will prove their organic affiliation with the Palestinian people without detracting from their Arab identity and pan-nationalist affiliation.

- Demand expanded cultural and administrative autonomy in which the elected High Follow-Up Committee and Palestinian Knesset members (MK) will serve as a mini-parliament.

- Demand full proportional representation in state institutions and proportional representation in the Knesset through separate direct elections of Palestinian MKs by Palestinian voters.

- Demand Israel to recognize its responsibility of the Nakba, and insist that Palestinians inside the state receive compensation and be allowed to return to their villages. Most of the villages stand on undeveloped public land, and the return of their inhabitants would not change Israel’s demography.12

- Demand that the Palestinian minority receive equal budgets in all fields as they fulfill their full financial obligations to the state. Democratize the major Palestinian representative institutions, led by the High Follow-Up Committee, through elections based on full proportional representation.

- Demand the release of the Islamic Waqf funds and properties and church funds and put them under a special committee affiliated with the Follow-Up Committee.

This program will build a new relationship between Israel and the indigenous Palestinian minority. It is an attempt to redress what happened to them as a result of the Zionist project and to build bridges between the Palestinian and Jewish societies based on respect and recognition instead of hegemony and domination. This new relationship would also block the spread of racism and halt the transition to an apartheid Fourth Israel.

The Palestinian minority’s struggle over the last seven decades to obtain some social privileges through parliament without putting forward a realistic vision of its relationship with the state and with Palestinians outside has led to a dead end. The Israeli political elite is united ideologically in its vision of the relationship of the state to the Palestinian minority and the future of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. This vision was presented in the “Deal of the Century.” The Palestinian minority in Israel and its political elite must work with the Palestinian leadership, headed by the PLO, to draft a new vision for ending the Israeli-Palestinian conflict now that it has become almost impossible to realize the two-state solution based on United Nations resolutions and international norms. Linking the fate of the Palestinians in Israel to those outside will help accomplish this.

I believe the vision should be a single federal democratic state, similar to the Federal Republic of Germany, on the lands of historical Palestine, guaranteeing the life and freedom of the Jewish and Palestinian communities. This state would be made up of eight to 10 provinces that are governed by provincial parliaments. In addition, there would be a federal parliament alongside a senate that represents the provincial delegates equally. An economic parity agreement would ensure economic cooperation and solidarity between the provinces. An international fund would be established to compensate and resettle Palestinian refugees if they want to return to the new state, and Jews and Palestinians would be free to live anywhere within its borders. This vision would also solve the issue of Jerusalem, borders, natural resources and the right of self-determination.

Endnotes

1 Gorenberg, Gershom; The Unmaking of Israel. New York 2011. (German: Israel schafft sich ab, Campus - Verlag 2012, Frankfurt)

2 Zangwill, Israel; The Voice of Jerusalem (London: 1920), p. 80.

3 Herzl, Theodor; Der Judenstaat in zionistischen Schriften, Bd. 1 (Berlin: 1934), p. 98.

4 Protocol of the executive committee of the Jewish organization 2.11.1947. also in Benny Morris, The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, 1947-1949, Cambridge 1987, p. 28

5 Avneri, Uri; Israel Without Zionism (New York: 1971), p. 262.

6 Die Zeit ist reif für normale Beziehungen. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung, Sept. 23, 1997.

7 For more information see: www.Adalah.org und www.mossawa.org

8 Liel, Alon; “Trump’s Plan for Palestine Looks a Lot Like Apartheid” in Foreignpolicy.com, March 1, 2020.

9 Hussein, Raef: “Breaking from Maze 2. Towards organizing a new socio-political representation for the Palestinian minority in Israel.” www.raif-hussein.de

10 Schutz Nationaler Minderheiten; www.nationale-minderheiten.eu

11 www.humanrights.ch.

12 Abu Sitta, Salman; The Right to Return is Sacred, Legal, and Possible (Beirut: Arab Institute for Studies and Publishing, 2001).