We set out with the understanding that equality is the foundation for our discourse, in both its ethnic and its gender dimensions. The transformative recognition of the right to equality was enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) in 1948 and explained in the words of Eleanor Roosevelt:

Where, after all, do universal human rights begin? In small places, close to home — so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any maps of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person; the neighborhood s/he lives in; the school or college s/he attends; the factory, farm or office where [s/he] works. Such are the places where every man, woman and child seeks equal justice, equal opportunity, equal dignity without discrimination. Unless these rights have meaning there, they have little meaning anywhere. Without concerned citizen action to uphold them close to home, we shall look in vain for progress in the larger world.

The right to equality is the key to all human rights, entitling every person to fulfill her or his potential unrestricted by social and political barriers of discrimination on grounds of race, religion, or national origin. Indeed, the essence of the UDHR lies in the entitlement of every person to experience the world unhampered by barriers imposed on the basis of their group status or classification. The human rights treaties have also emphasized that states must ensure the equal right of men and women to the enjoyment of all human rights — civil and political, economic, and social — a commitment that culminated in the 1980 Convention for Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), which has been ratified almost universally. We are agreed that the value accorded to the right to equality, both on grounds of gender and of national origin, is a neglected value in the socio-political fabric of Israeli and of Palestinian society. The neglected status of the right to equality resounds bitterly in the realities of the occupation.

The Failure to Apply the Paradigm of Equality

In this context of occupation, the application of the concept of conflict resolution to Palestine-Israel relations is complex. While conflict has been integral to the relationship between Israel and Palestine, in the shape of conflicting perceptions of rights, the dynamic development of asymmetry of power has made the concept of conflict misleading. Open acknowledgment of this asymmetry and introduction of a basis of reciprocity are essential to move forward toward equality and true conflict resolution.

We are witness to a tragic failure to incorporate the paradigm of equality into Israel-Palestine relations. This failure is evident in many of the internal political dynamics within each society and is then manifest also in the military and diplomatic conduct of the two parties. As regards the value accorded to equality in each of the two societies, there are some elements that have a similar core, but there are also crucial variations. Within the two societies, equality is regulated in large part by constitutional provision, political representation, and personal law — the body of law concerned with marriage, divorce, and personal status. In applying the foundational principle of equality to Palestine-Israel relations, the asymmetry and the violations are clear: Irrespective of how the occupation is perceived as such, the reality is inequality.

Internal and external forms of inequality do not exist in different, disconnected worlds; they are constitutive elements of the one interconnected world we all live in and have an ongoing interactive and aggravating impact.

Israel has a severe equality deficit in its written constitutional documents. The basic laws passed by the Knesset guarantee the rights to human dignity and liberty but omit the rights to equality, to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion; and to freedom of expression. This deficit is the result of the rifted nature of Israeli political representation, with the religious parties forming a lobby in the Knesset that opposes inclusion of the missing rights. These missing human rights have, instead, been recognized and to a considerable extent enforced through the case law of the High Court of Justice as regards both the rights of the Arab minority and the right of women to equality except in religious laws governing marriage and divorce. Nevertheless, the failure of the Knesset to include the right to equality in the Basic Laws reflects a failure to regard equality as a constitutional imperative and foundational value of the state.

Indeed, there is a serious deficit in the implementation of equality in practice. The rhetoric of leaders of Jewish political parties rejects full and equal political partnership and cooperation with Arab parties in the Knesset. There are severe equality gaps in educational achievement in different sectors of society. Economic inequality is high, and among Organisation for Economic and Cooperation Development (OECD) countries, Israel is next only to the United States and Mexico in inequality between the highest and lowest income groups and in social welfare and poverty indicators.

The gender gaps are wide and, furthermore, rather than making progress toward greater gender equality, the situation is worsening. In 2019, Israel fell 18 places in the gender gap index, to be ranked at 64th out of 153 countries. Israel ranks only 83rd out of 193 countries regarding the number of women in parliament (23%) and 109th regarding ministerial posts (17%).

Discriminatory Legal and Social Systems

Israel’s personal status law is determined by the religious law of the three monotheisms and, as such, endorses patriarchal marital regimes in which women and LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) individuals are not entitled to equality and in which they are excluded from appointment as judges in the religious courts, which have jurisdiction over them. In the majoritarian Jewish law, women suffer discrimination as regards the legal regulation of divorce, marital infidelity, and remarriage. Religious patriarchy has recently been further intruding into the public space in political parties, the army, public transport, public ceremonies, and institutions of higher education. In 2017, in her report on Israel,1 the United Nations special rapporteur on violence against women pointed out that the level of violence in Israel varied between the different ethnic groups, with the greatest number of femicides being in the Arab community. She observed that, in the context of Israeli-Palestinian conflict, violence against women is a phenomenon that occurs on both sides of the divide and that combating and preventing violence against women will ultimately contribute to each society’s growth, bridge divided communities, and contribute to peace by removing obstacles to the full participation of women in the peace process.

The constitutional, legal, and social system of Palestine has to be viewed in the context of the occupation. Life promises Palestinians in general and the refugees in particular an often-valueless status due to nonrecognition of Palestinian identity, denial of citizenship, severe restrictions on freedom of movement, lack of resources, lower quality of life and life expectancy, poor education, lack of decent work opportunities, and constant encroachment on their land rights, along with humiliation, violence, and various modes of political imprisonment. Although Palestine has included an equality clause in its constitution, according to which “Palestinians shall be equal before the law and the judiciary, without distinction based upon race, sex, color, religion, political views or disability,” it has not brought about change on the ground regarding gender. Indeed, it is important to understand that even now. a Palestinian baby girl may be regarded as a “birth accident.” Nor should we forget the multiple levels of discrimination that Palestinian women face as women on the basis of custom, religion, and all the invisible walls that prevent women’s active participation in all fields of human activity. Women’s participation in public life remains limited compared with men. The percentage of women's participation in the civil sector reached 44% of the total employees, yet the number of those who hold the rank of director general and higher is only 13%.

In addition to all the multiple hardships of occupation, Palestinian women suffer from gender-based violence, economic discrimination, and lack of political representation. In Palestine, the tension between nationalism and feminism has been accompanied by the increasing trend of Palestinian women facing multiple forces that actively suppress their politicization and participation in political spaces. The Palestinian Legislative Council has maintained a 20% quota for women since 2006 — a quota that Palestinian activists and women’s organizations fought hard for — but the de facto participation remains low and, of the PLO Executive Council’s 15 members, only one is female. Women make up only 5% of the Palestinian Central Council, 11% of the Palestinian National Council, and 14% of the Council of Ministers. Also, active women ambassadors make up only 11% of the diplomatic service. Moreover, only one woman holds the position of governor out of 16 governors.

The personal law and the family law in Palestine are based on the millet system, with a majority governed by sharia law. This provides for a marital framework based on “complementary” rights (as opposed to “equal” rights) between the two spouses, allowing for roles and rights differentiation on grounds of gender, with women surrendering their right to equality, allegedly in return for their entitlement to maintenance and protection. On this basis, women suffer discrimination in regard to minimum age of marriage, polygamy, divorce, custody of children, and inheritance. When they are considered “disobedient” to their husbands (nushuz), they risk forfeiting even their minimal rights.

Economic Discrimination Against Women

The economic situation of women differs considerably between women from different ethnic groups in Israel and between Israeli and Palestinian women. Different surveys and studies illustrate discrimination against Palestinian women in economic life.2 Although the proportion of females in all stages of education has exceeded the proportion of males, this has not contributed to narrowing the gap between male and female participation in the labor market. The proportion of women in the labor market does not exceed 17%, with women concentrated in low-paid, feminized professions. Furthermore, it has been noted that Palestinian female students outperform their male counterparts in academic achievement and excellence but are nevertheless, placed lower in the economic hierarchy.3

In Israel, the female labor force participation rate is 60%, and the rate for Arab Israeli women stands at about 40% — nearly double the rate in 2003. However, Israel is also ranked as one of the four OECD countries with the highest gender-related wage gap. In other words, women are participating in large numbers but are severely underpaid for their jobs.

With regard to social welfare, the coronavirus crisis caught Israel with a high proportion of people living in poverty, an underfunded health system, a social protection system that offers less than generous cash transfers, great dependence on nonstate service providers, and understaffed social services. The impact of this crisis is expected to be most severe for the most vulnerable segments of the population, who were dependent on cash transfers and social services before the pandemic hit. The temporary and populist allocation of funds to unemployed Israeli citizens and residents, without a state budget, is unsustainable and creates an illusion of economic security. For the Palestinian population, the economic fallout from the coronavirus is a disaster. Even prior to the pandemic, more than a quarter of Palestinians lived below the poverty line. The share of poor households is now expected to increase to 30% in the West Bank and to 64% in Gaza. Even more striking is the (official) youth unemployment rate of 38%, well beyond the Middle East and North Africa’s regional average.

Religious Nationalism and the Devaluation of Equality

Israel and Palestine share a trend toward an increasingly theocratic culture. Religious nationalism is a growing characteristic of Israel-Palestine relations. It is an impediment to the recognition and implementation of the right to equality both within our societies and between them. It is also a shared challenge, which we must address together in order to establish the right to equality as the key to all human rights, to democracy, and to a just and sustainable political solution.

Deference to religious values, embodied in legislation, is shared as regards the endorsement of gender hierarchy in the family which, as the basic unit of society imbues both societies with a patriarchal ethos. This negation of women’s equality in deference to religion and tradition is a clear violation of the obligations of Palestine and Israel under the human rights treaties, including CEDAW, which they have both ratified. Discrimination against women cannot be justified by claims to the right to freedom of religion. Indeed, discrimination against women in the name of religion is a clear violation of women’s human rights.

The devaluation of equality as the key to human rights and a decent society is highly pertinent to the relations between the two peoples. The occupation of Palestine by Israel has produced an inherently unequal situation of the domination of one people by the other. The inherent inequality is exacerbated by the long-term perpetuation of power through settler colonialism and de facto annexation. These trends not only fail to introduce equality but entrench deep ethnic and national inequalities. It is imperative to reverse these trends to bring hope of a decent society for each of the two peoples.

In seeking a solution, it is crucial to introduce equality as the key element. The more radical factions on each side reject the recognition of the other’s equal entitlement to self-determination. This radical view has a strong resonance in the mainstream political process in both societies, which are either insufficiently aware of or deliberately reject the principle of equality and are not robust in their resistance to the rhetoric of inequality, in which the other side is dehumanized. Indeed, this is a deliberate strategy used by militant leaders on both sides. This is a way to promulgate and prolong wars and continue to profit from them.

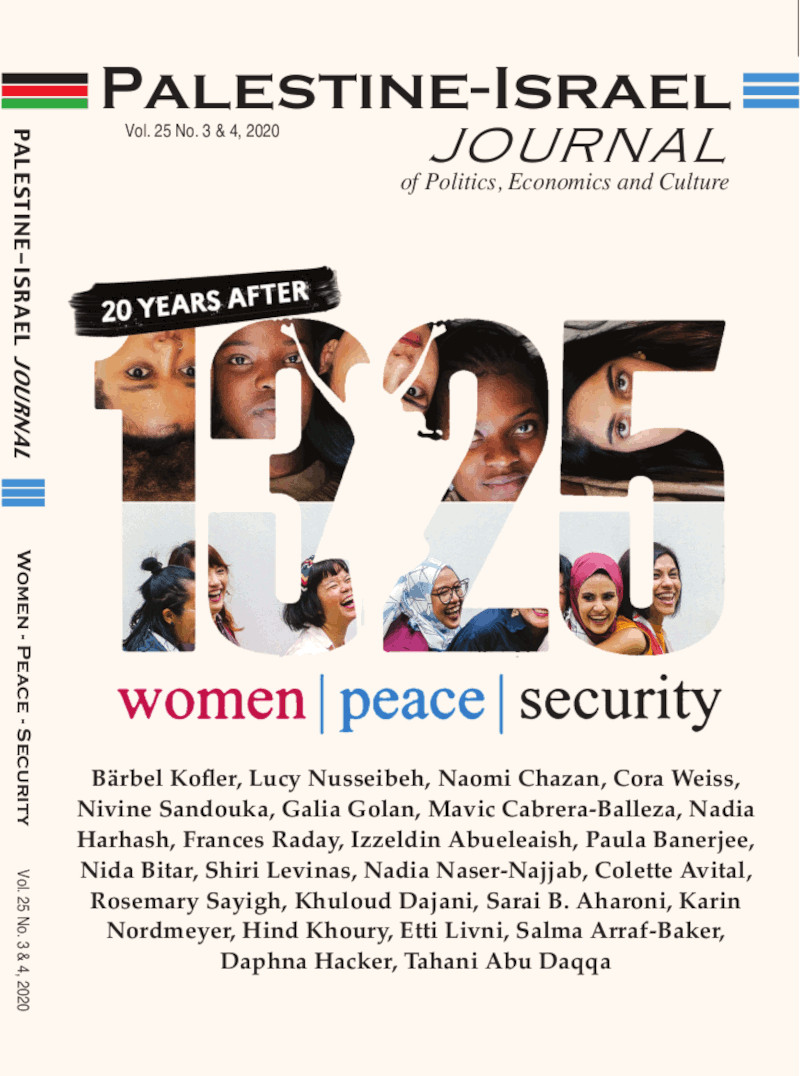

Since 2000, UN Security Council Resolution 1325 and its follow-up resolutions have addressed the impact of war on women and the importance of women’s full, equal, and meaningful participation in conflict resolution, peacebuilding, peacekeeping, humanitarian response, and post-conflict reconstruction. The Security Council’s requirement of women’s full and equal participation gains even greater traction in our local environment. Women are more fully aware of the costs of inequality and the hatred and violence that accompany it, although there are women who align with militant and oppressive views. Women have been active in peace movements on both sides. There is much literature that shows the cost of occupation and militarization for women and girls in increased exclusion, stereotypes, and violence against women.

The Israeli occupation, which is inevitably oppressive, also subjects Palestinian women to gendered forms of violence and empowers patriarchal structures through its relentless colonization and fragmentation of land and communities. This has combined with forces within the Palestinian and international communities to contribute to the weakened political role of Palestinian women. The militarist mentality prevailing in Israeli society has a detrimental effect on the equality of women in both societies, albeit in vastly differing modes. Palestinian women are often threatened and harassed by Israeli soldiers of both genders, and their position in Palestinian society is weakened by the militarization of the conflict. Israeli women are disempowered in all walks of life — politics, civil service, educational institutions, and even academia — because of the overrated merit endowed to achievements in army service, especially in the higher echelons. In Palestinian society, militarism has had a continuously demoting effect on women’s agency, an effect which is especially strong in Gaza under Hamas. It is also evident in the securitization of the public sphere throughout the occupied territories, which manifests in armed solutions for social problems.

Transforming Mindsets to Advance Equality for Women

In conflict zones, the situation is harsher, mainly since the violence, cruelty, constant uncertainty, fear, “security,” and lack of safety severely undermines women’s ability, mobility, and accessibility to transformation. We believe that women can, and therefore must, transform the paradigm from military to human security and from victimhood to inclusive humanity. It is because of this that a decent human society requires the full realization of equality for women. The rise of women must go beyond a merely symbolic makeover that permits a few distinguished women to ascend to positions of leadership. It must extend to the empowerment of the broad masses of women in their entirety, which requires affording women equal opportunities to be active participants outside the family. It is essential that realistic and substantial value be given to women’s multiple roles in the society, the economy, and the family as they constitute an indispensable contribution to the sustainability of a sound social structure.

We need to transform mindsets away from the acceptance and entrenching of inequality, whether with regard to individual people, especially women, or with regard to peoples. Such a transformation involves a huge leap away from any form of entitlement, including that associated with religion and also with (perhaps self-proclaimed) victimhood. Resolution 1325, with its insistence on women’s agency and involvement, in addition to the need for protection against gender-based violence, marked a significant step toward the indivisibility of equality for women and humanization. In unequal power situations, it is all too often only the powerful who are heard or who are taken seriously. As women become more undeniably visible as agents and audible as representatives of more than half the world’s population, the hope is that this will progress to become a seismic transformation and the whole system can start to shift, including the inequalities across the occupation lines.

_________________________________

Endnotes

1 Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences. (United Nations: 2017), A/HRC/35/30/Add.2.

2 https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2979/jmiddeastwomstud.8.2.78?seq=1

3 Palestinian Statistics (PCRS, 2011).