United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 was full of promise, not just when it was first passed in October 2000 but for many years afterward. It brought hope to women peace activists for a variety of reasons — not least its recognition of the importance, and indeed the necessity, of actively involving women in peace processes. It stressed the need for women’s meaningful participation in negotiations along with the need for protecting, even prioritizing the rights of women affected by war or conflict.

In essence, it addressed the problem of “new wars” in which the dangers are more to civilians than to actual fighters and, in particular, the problem of the power relations and unequal gender norms that are part of both militarism and actual wars. What is more, it is not (and should not be) just about adding women “to the table” or to the security services but about adopting a gender transformative approach that liberates both women and men from crippling violence-perpetuating gender stereotypes as well as from the horrors of actual war.

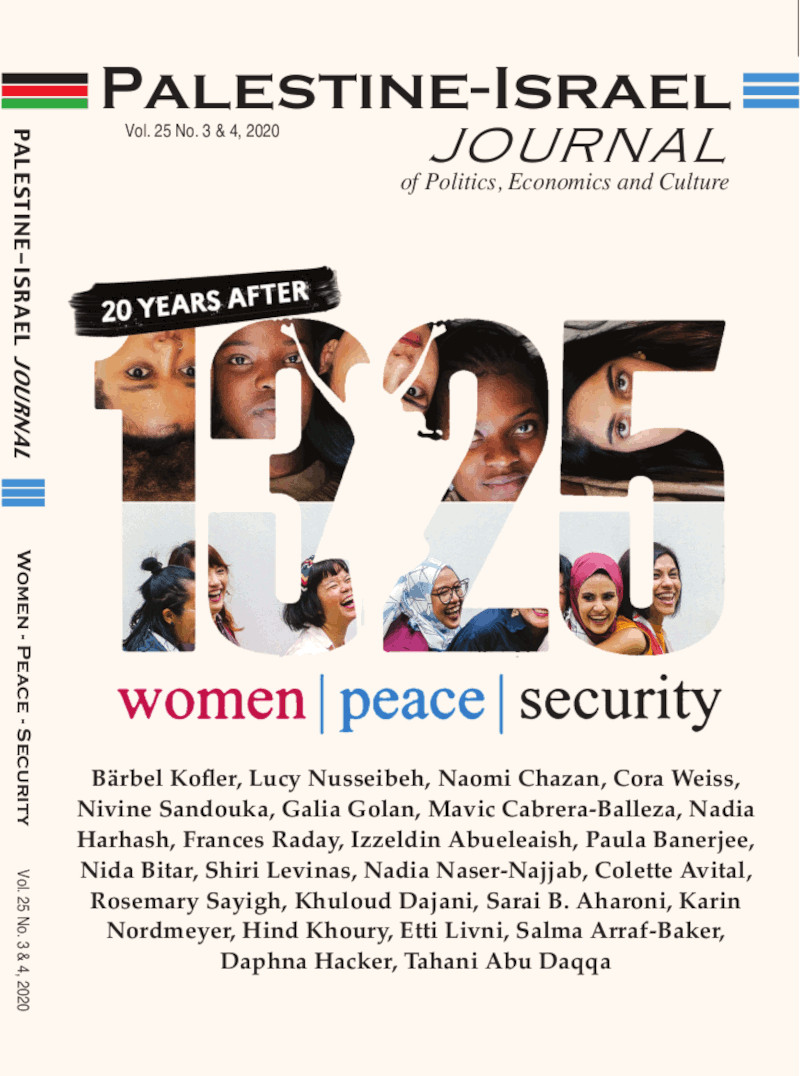

The emphasis of the resolution was on agency and action and on the necessity of a leading role for women on an equal footing with men and less on women’s suffering and their need for protection. What was initially an opening for the engagement and the representation of women in negotiations and peace processes, bringing women to the forefront, has now, however, after 20 years, become shortened to “women, peace, and security” or even simply WPS. All too often the emphasis is now on the “security” component of this, with “security” perhaps being understood as meaning an end to gender-based violence, or just protection, or perhaps, via a twist and a stretch, women’s recruitment into security forces. Somehow it seems as if the key element of 1325 regarding women’s agency, and above all, women’s voices being heard and respected, has been silenced by the age-old refrain of the need to protect women. While protection against gender-based violence is undeniably vital, especially in situations of war or conflict, and civilian protection (preferably unarmed) is one of the key elements necessary for ending wars and building peace, it risks leaving the unequal male-dominated power structures intact and does nothing to increase women’s participation in decisions regarding their current safety and their future; if anything, quite the contrary. What is more, the 10 UN resolutions subsequent to 13251 have also focused more attention on women as victims rather than women as agents.

Early Cooperation Between Palestinian and Israeli Women Despite Emergence of Militarized Uprising

The initial hopes around 1325 were really effective in bringing together Palestinian and Israeli women in its early years. There were joint seminars in the United States, followed by joint meetings, despite the damage done by both the violence and the negative propaganda during the heavily militarized uprising that began in 2000 that had pushed apart most Palestinian and Israeli women who might have been allies. Later, as the context became more complex and less hopeful, these joint seminars morphed into unilateral meetings. The Palestinians, for instance, met for strategy discussions in Ramallah. Despite the overall impasse and very discouraging atmosphere, 1325 encouraged preparation and action. The assumption was that women would be at whatever negotiations would be taking place, in equal numbers with men, and bringing diverse opinions, and that therefore it would be good to train women in negotiations and public speaking, including how to address and influence men not only in politics but also, in the military and in security. But this was perhaps optimistic as regards the direction of such influences.

1325 is sometimes described as having three pillars: participation, protection, and prevention, although the “prevention” pillar seems

(interestingly) all too often to be forgotten. Even though they were not spelled out, the steps to the implementation of the “participation” and “protection” pillars seemed reasonably clear 10-15 years ago (see the PIJ issue on Women and Power, 2011): increasing the numbers of women at the table during negotiations — while being aware that women are not at all necessarily more “peaceful than men”; — training women as negotiators and mediators; bringing women activists to the forefront; and increasing the focus on human as opposed to military security. But these steps no longer seem so clear. The scene has become muddied, despite the fact that the Palestinian Authority (PA) has already produced two National Action Plans (NAP) for 1325.

1325 in Palestine Is Dominated by the Occupation

The Palestinian relation with 1325 is of course dominated by the Israeli occupation. The first NAP, in 2017, focused very understandably on the second pillar: protection for Palestinian women under the occupation and their empowerment toward steadfastness (sumood), which is more or less the only form of resistance left in the present circumstances. What is more, in spite of the pandemic and dire economic conditions, both current and forecast, the PA launched a second NAP in November 2020 via a genuinely consultative process and with a forward-looking agenda, including ensuring that there will be funding for it. The report from the high-level launch of the second NAP mentions “meaningful implementation,” including setting up a multistakeholder financing mechanism and “enforcing linkages” between the NAP and other important international frameworks and agreements to ensure a higher level of women’s protection and participation. While this clearly has potential, the occupation, the fragmentation of Palestinian

society, and the absence of human security and of any hope for peace also make it doubtful how much can actually be achieved.

Sadly, Palestinian society has become increasingly militarized since the signing of the Olso Accords in 1993-94 with the establishment of a large number of security services (as much for the protection of Israeli security as for Palestinian) and the subsequent and continuing rapid spread of both legal and illegal small arms. It has also become increasingly fragmented, and the dangers of physical violence are ever present, primarily from the occupation but also from within Palestinian society.

The violence in the Israeli-Palestinian relations, however, is as much structural as it is physical, and it is the structural long-term violence entrenched in the Oslo agreements that needs to be challenged and changed and that women’s voices at the peace table should be addressing, among other things.

Growing Focus on Militarized Security Rather Than Safety

“Security” is not the same as “safety,” and safety is perhaps what peace should be able to bring. Palestinians — women in particular but in fact all Palestinians — need safety; they need to feel and be safe. International laws such as the Fourth Geneva Convention, the Responsibility to Protect, the Global Action Against Mass Atrocity Crimes, and 1325, as well as multiple UN Security Council resolutions passed on the situation of Palestine (since Nov. 29, 1949), should have led to human security and safety for Palestinians.

There seems to be slippage, both in the world as a whole and in the context of 1325, toward an increased emphasis on militarized security as opposed to actual safety. This in itself and by its nature excludes women, not because women are necessarily by nature more peaceful than men but because of the traditional male domination in the field of military security. During the early years of 1325, there seemed to be a shift away from “national” or “military security” and toward people-centered “human security” — the safety and security connected with day-to day-living conditions, where women, as major actors in civil society, could have played a key role. The shift in recent years, however, was in the other direction, away from human security and back toward seeing security in purely military terms. Yet, with the spread of the pandemic and the need for awareness of health issues and a broader understanding of “safety” if not of “security,” human security is again appearing in the general discourse.

One of the major shifts in the moves toward implementation of 1325 — whether in the PA or in other countries, such as Jordan or the United Arab Emirates — has been toward increasing the number of women in this traditional bastion of male security. It is possible that this can help with a shift in mindset toward equality between men and women, but the tendency will surely be to make women less peaceful and more inclined to try to seek solutions via military security. The “security sector” is a traditional bastion of “masculine values” — physical strength, assertiveness, fearlessness, etc., including treating women as objects of protection. Expertise in this area is centered on violence rather than nonviolence or peace.

Participation of Women Without Agency and Without Shifting Power Relations Is Not Enough

The WPS agenda has been complicated by an emphasis on “security” instead of “women” and/or “peace” and by lack of progress, perhaps caused by pushback against feminist gains. 1325 as an international law needs to be refocused on the need for peace as well as for need for women to be involved with peace processes, and the push toward integrating women into male security apparatuses and away from building peace must be resisted. There needs to be emphasis on “meaningful participation” of women or, if necessary, on redesigning the table rather than just giving a woman or two a token seat at it. The shift in mindset set in motion by 1325 two decades ago and which should have made women as present, visible, and audible as men in all negotiations everywhere has not happened. Moreover, it has become clear that the mere presence of women is not sufficient in itself. What matters is how much authority they have and how much they can influence outcomes with relation to peace, power, and gender. In order to really make the most of the potential of 1325, work needs to be done with regard to ensuring that enough women with a good understanding of gender and from a wide range of backgrounds are at the table. There is a connection between issues of inequalities regarding participation and structural violence.

Work also needs to be done on masculinities and educating toward a gender-transformative approach: challenging traditional gender norms, addressing traditional patriarchal mindsets, and shifting traditional structural power imbalances. Gender inequality also contributes to structural violence within society, preventing women and girls from fulfilling their potential and reducing them to needing “protection” instead of empowering them.

The Need to Aِِctivate the Prevention Pillar

Overall, there needs to be a shift in mindset toward gender equality and a corresponding shift away from structural violence, whether as violence against women or in the context of the occupation. 1325 offers the possibility for such structural changes. These could perhaps be implemented by reactivating (activating?) the “prevention” pillar, as real prevention would address the roots of war and militarism and would involve shifting power relations and bringing about social justice. Without this change, the emphasis on the protection pillar runs the risk of making things into “women’s issues” rather than including women as equals, even if they are “at the table” in equal numbers with men, and even though “women’s rights” are of course “human rights.”

But Palestinian women do need protection as well. They are victims of war and occupation, as well as agents of resistance and reconstruction within civil society.

Absence of Peace Process and Strengthening Patriarchy Sideline Women in Palestine

It is hard to see how Palestinian women can be involved in anything directly connected with 1325 at the moment. In the current situation of apparently endless occupation, the imminent threat of annexation of the most productive areas of land, and the recent “peace accords” with the Gulf states which bypass the Palestinians’ need for peace and justice, there are no indications of a likelihood that more women will be involved in any local peace processes. No doubt this is due to the absence of any peace process

and the increasing hopelessness with regard to the occupation.

Meanwhile, as the region (and the world as a whole) seems to turn more to religion and tradition, patriarchal values become stronger and women are less visible in all spheres. When CEDAW (the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women) suddenly came to the attention of some of the more conservative leaders in Hebron in late 2019, there were large-scale protests against it and against the PA’s raising of the marriage age from 15 to 18 for girls and 16 to 18 for boys. The demonstrators called for preventing feminist organizations from renting office premises and for barring the children of feminists from schools. It is important to note that this sudden discovery of and backlash against CEDAW was taken on by groups of conservative women as well as men.

Lessons to Be Learned from the Pandemic

In the Palestine-Israel Journal on “Women and Power” published

nearly 10 years ago, I wrote about the need to shift mindsets away from

military to human security. This need is more urgent than ever, although

it appears that with the combination of fear and isolation as well as

interconnectedness created by the pandemic, a growing appreciation of the

need for human, as opposed to military, security is emerging in some places.

But perhaps what is most important is to get away from the so-called “security” that is based on fear and to focus on the “women” and “peace” components of the WPS agenda and make it clear that peace must involve demilitarization.

Palestinian women, like most women around the world, have been particularly hard hit by the pandemic, whether because of having to endure lockdown in crowded conditions with no respite, or losing jobs, or suffering increased gender-based violence. We also see examples across the world of the power, courage, and effectiveness of women’s leadership in dealing with the pandemic. This is a clear announcement to all who might not already know it of the need for women in leadership positions. It also serves as a reminder that in this longstanding occupation, women can surely make a difference. The pandemic reminds us all too acutely of the importance of prevention. Perhaps this can be applied to war as well. Perhaps the pandemic can provide a way to raise awareness of the need for more human security and for women to join together across the unequal borders of the occupation and try thinking together about a more secure future. As Susan Sontag reminds us: “Courage is as contagious as fear.”

Women Must Ensure the Promise of 1325 Is Fulfilled

Part of the policy of the occupation seems to be to induce despair and demoralization, which in themselves create a vicious cycle, especially for women who risk being crushed under the weight of two-fold structural violence of oppression by the occupation and by patriarchy. 1325 promises agency and a key role in peacebuilding and, therewith, the key to lasting structural changes. We must not allow it to be hijacked by those who would subsume women’s participation to the male-dominated security sphere and keep them away from the negotiating teams, whether at the governmental or civil society level.

We need to work with radical hope and make sure that 1325 keeps its promise.

___________________________

1 For instance, UNSCR 1820, which recognizes rape as a tool of war and classifies it as a war crime, while extremely important in itself, brings the focus entirely onto women as victims.