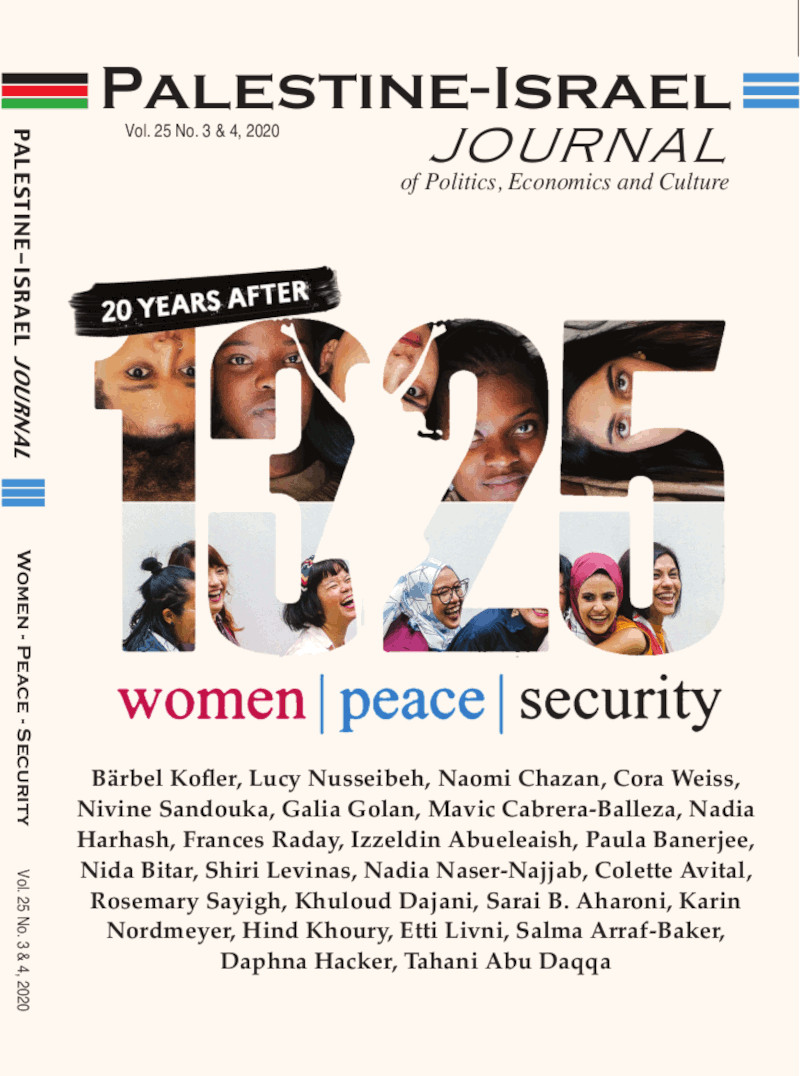

In October 2000, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 1325 on women, peace, and security. The resolution supports the crucial role of women in the prevention and transformation of conflicts, peacebuilding, political negotiations, peacekeeping, humanitarian response, and post-conflict reconstruction. UNSC Resolution 1325 stresses the need for equal participation and full involvement of women in all efforts for the maintenance and promotion of peace and security and urges leaders of

member states to increase the participation of women in decision-making processes and encourages them to incorporate gender perspectives in all United Nations peace and security efforts. In addition, it calls on all member states to take special measures to protect women and girls from gender-based violence, particularly rape and other forms of sexual abuse.

The Importance of Women in Conflict Transformation Efforts

Leveling the playing field — where women and men have equal chances to become socially and politically active, make decisions, and shape policies—is likely

to lead over time to more representative, and more inclusive, institutions and policy choices and thus to a better development path. – The World Bank, 20112 I.1

For a long time, women were portrayed as victims of violent conflicts. They pay the ultimate price physically, emotionally, and socially and are left with no agency or institution to help them. They often find themselves alone, which enhances their sense of victimhood rather than survivorhood. When women see themselves as victims, it limits their ability to engage in efforts to end conflicts, build peace, and transform relationships. While women are heavily impacted by war as they experience war differently from men, their input, views, thoughts, and skills are rarely considered when men sit at the table to negotiate a “peace” treaty. Throughout history, women often found themselves excluded from decision-making processes. Men not only ignored women’s participation but also persecuted them when they attempted to make their voices heard.

There is enough evidence from successful women’s integration into peacebuilding efforts to prove that bringing women to the peace table improves the quality of agreements reached and enhances the likelihood of implementation because of the unique skill sets and experiences that women possess. Liberia, Rwanda, North Ireland, New Zealand, Tunisia, and Bosnia-Herzegovina are some examples.

Gender Roles in Conflict Resolution

Research done by UN Women in 2012 found that in 31 peace processes conducted between 1992 and 2011, women’s representation in the negotiations was under 9%.2 Therefore, women must find a way to get involved in conflict prevention efforts, peacebuilding strategies, and negotiations. The world must acknowledge women’s role in transforming conflicts and sustaining peacebuilding efforts. Women not only have the capacity to do so but, because they are those who are primarily impacted by violent conflicts, they bring a different set of skills to create sustainable peace agreements based on needs rather than political positions and greed.

Yet when women sought a role in politics, they were convinced that they needed to act like men in order to fit into a political system made by men for men. This notion found its way into the conflict prevention/resolution field as well. They needed to think, act, and sometimes look like men to succeed. They had to suppress their emotions and traumas so as not to be viewed as weak. Many women adopted this notion and lived by it when they were in office, and that is one reason why they did not have a significant impact on gender equality and representation policies. One example that comes to mind is British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who was in office from 1979 to 1990.

Research shows that men and women have different set of skills when managing conflicts. There are essentially five main types of conflict management styles: competition, accommodation, avoidance, collaboration, and compromise. Women tend to use cooperation, collaboration, and compromise as conflict management styles while men use competition and avoidance. The strategies women adopt take into consideration resource sustainability, effective security plans, strategic partnerships, trauma healing, reconciliation, advocacy, mobilization, and inclusivity, which make peace agreements more likely to work more effectively.

In addition, women bring to the table less ego, more integrity, a huge sense of responsibility, a strict code of ethics, and a broad view of interests rather than narrow personal gains.

The Liberian women’s experience showed us that women there tackled all the above as formal and informal ways to engage in ending years of internal conflicts led by warmongers who drained Liberia of all of its assets. Looking at Liberia now gives us more determination to fight.3

The Case of Palestine

In June 2015, the Palestinian government endorsed a national strategic framework for building a National Action Plan (NAP) for implementation of UNSC Resolution 1325 in 2016. In 2020 the Higher National Committee for the Implementation of UNSC Resolution 1325 presented its second NAP. Palestine was the second country in the Arab world, after Iraq, to do so. The NAP constitutes a comprehensive action framework to include Palestinian women in peace, security, and humanitarian processes and guarantee their participation in decision-making processes.

When looking at the status of women in Palestine, statistics show that Resolution 1325 has had a very minor impact on women, peace, and security needs in Palestine. The majority of Palestinian society does not yet believe in equality between men and women. A huge percentage of men and women still believe that the main priority of women is to take care of the household. Many do not believe that women should work and, if they do, they allow it only because it benefits men economically. Violence against women in Palestine is still not condemned socially, and there are no strict laws against its perpetuators.

While efforts to adopt Resolution 1325 continue in Palestine, it is difficult to know how many women are actually aware of it. Most of these efforts take place in closed rooms where the elite work on behalf of specific groups of women who enjoy certain degrees of privilege. This is the situation despite the Palestinian Authority’s attempts to advance gender equality within its governance structures and it efforts to amend the Palestinian Basic Law (2002) related to women to a more coherent laws (2003)4 that enabled the creation of a Ministry of Women’s Affairs, and the establishment of 22 gender units across government sectors.

Studies about attitudes toward Resolution 1325 in marginalized groups and communities in the West Bank and Gaza have found that most women do not know anything about it or its implications for their lives. Some had heard of women-led organizations that mentioned some sort of training here or there which they did not see as relevant to their realities or needs. These observations are based on my work in the field and on research done by UN Women and other international NGOs.5

While all reports examining the challenges facing Palestine in implementing Resolution 1325 rightly emphasize the Israeli military occupation and its discriminatory policies as a context for these challenges, they fail to focus on the role cultural, social, and economic norms play in this context. Furthermore, one must consider the political fragmentation, the loss of a collective sense of identity, and the confusion over the status of the residents of the West Bank and Gaza after the Oslo Accords about whether they are citizens of a country-to-be or still an occupied group of people with no access to resources or control over their borders. All of these constitute key challenges to advancing gender equality and the Resolution 1325 NAP in Palestine.

Looking at the history of UN resolutions related to Palestine, Resolution 1325 is not that different from any others. It lacks any mechanism of implementation and of accountability for stakeholders who fail to advance gender equality and women’s participation in the peace process and negotiations arenas.

Palestinian women are no exception to the women all over the world who are not part of the elite or not born to privilege and suffer from exclusion at all levels of decision-making processes. Although Palestinian women are recognized for their contribution to the struggle for freedom and justice in Palestine, they still have no equal opportunities for participation in political, social, or economic processes.

With all due respect to efforts made to advance women, peace, and security integration on the political levels in Palestine, I still argue that the majority of Palestinian women have no clue about what they stand to gain through the adoption of Resolution 1325. Attitudes that reinforce gender inequality still prevail among Palestinians, and laws continue to treat genderbased violence as a “family” issue to be dealt with by the tribal system rather than by the legal system. When women in Palestine are exposed to violence, they rarely find a place to report to or seek refuge. In many cases, they are sent back to their families even when there are serious threats to their lives. This can be seen in campaigns launched against the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) treaty, early marriages, and “honor” killings. When women take to the streets to raise their voices against gender-based violence and inequality, they get attacked by both men and women who see this as a challenge to religious and social norms. Again, I argue for the sake of underprivileged women in my society who have no access to any facility, institution, or individuals who can support them.

Women and Peacebuilding in Palestine

Since 2014, I have been working with 125 organizations in the peacebuilding field in Palestine and Israel. Women in this field are also being marginalized by national, cross-border, and international entities; anti-normalization groups; right-wing entities; BDS supporters; and funders who work against us. The only manifestation of Resolution 1325 I see is in the work being done at the grassroots level. This work is still seen in a negative light, however, and is criticized for lacking impact. Although other systems have not brought about any change the dynamics of the Israel-Palestine conflict, still it is this field that people point fingers at. Nonetheless, it is the only field that has been actively engaging marginalized women from both Palestine and Israel in inclusive political activism, providing them with skill-based training and fair opportunities to present their narratives, and engaging them in trauma healing and reconciliation efforts in ways that keep them authentic and true to their identity.

I believe that women should be involved in every aspect of our lives and play leading roles in changing everything that has not been working for all humanity, but for this to happen in Palestine and in the entire world, some radical, comprehensive, and sustainable changes in the educational system are needed. Women should not keep paying the price of dysfunctional social, political, and economic systems created by men to serve men alone. Women must fight for true gender equality, not just superficial representation in parliament or in the diplomatic corps. They should be free of political affiliations, so they do not end up acting like a chorus repeating men’s main dominant song. Representation of women should not be exclusive to a certain species of elite or privileged women who normally have no impact on making radical changes to the status of women in Palestine. Women can liberate themselves and others when they reconcile with their own identity and claim their place as change-makers rather than just a number in a quota.

Yes, the Israeli occupation has a huge influence on women’s status, rights, and representation. It targets every aspect of the human security women in Palestine have or need, changes the fiber of Palestinian society, pushes women to feel and act like victims, and paralyzes them when they want to move forward with their dreams or be free. The Israeli occupation must end and should end soon, but I do not think if it ends now, women in Palestine will enjoy freedom, security, and justice. The social, economic, and political norms in Palestine continue to keep women down, ignore their rights and see women as less than men. Therefore, while we all struggle to end the Israeli occupation, we must continue to struggle for fair representation of women in all walks of life alive. We must not give up and should build a comprehensive strategy for radical change in all the man-made systems that rule our lives.

Men in Palestine should reconsider their position toward Palestinian women and see them as partners with full rights. They should join the struggle for more equal representation of women and should find ways to stand by women in Palestine rather than against them. They need to change the traditional way they think of women and start viewing them as the equals that they deserve to be.

_______________________________

Endnotes

1 The World Bank. (2012). World Development Report 2012: Gender Equality and Development. Retrieved from openknowledge.worldbank.org: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/4391/9780821388105_overview.pdf?sequence=6&isAllowed=y

2 https://www.nytimes.com/2020/10/13/us/women-peace-process-afghanistan-sanam-naraghianderlini-.html

3 https://www.peacewomen.org/sites/default/files/The%20Role%20of%20Women%20in%20 International%20Conflict%20Resolution.pdf

4 https://www.palestinianbasiclaw.org/basic-law/2003-amended-basic-law

5 http://www.miftah.org/Publications/Books/A_Vision_for_Palestinian_Women_on_the_International_Review_En.pdf