Two days before leaving for Dublin on a study tour that was to include a visit to Belfast, I was asked to make sure that I had a valid visa to the United Kingdom in order to be able to visit Belfast. Although I usually have valid visas to the United States, the UK and Schengen countries, I was worried about the possibility that the UK visa had expired without my being aware of it. When I checked my passport, I was relieved that my visa was still valid and I would have no problem crossing the border between the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland.

We had two very intensive and fruitful days in Dublin, meeting people from across the Irish political spectrum and a good number of academics and experts from whom we learned a lot about the background of the conflict and the ups and downs of the efforts to achieve a political solution that is finally succeeding in putting the carriage on the tracks to its final destination: Peace.

The next station was Belfast. Together with our hosts from the Irish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and my colleague Hillel Schenker, the Israeli co-editor of the Palestine Israel Journal, I took the train with no fears or hesitation on crossing the border as long as I had a valid visa to the UK.

We arrived in Belfast without anyone asking us about a visa or even looking at our passports. In some way it was disappointing, since I was ready to proudly show my visa to the border police between the Republic and the North because they did not show up. Possibly my disappointment has much deeper roots in my psychology— first, because there is no country in the world except Mauritania that allows Palestinians to cross its borders without a visa; and second, because even in my own homeland, Occupied Palestine, I can’t move or go anywhere without making sure that I have my official identity card — not just any photo ID — in my pocket, knowing that at any moment, anywhere, I can be stopped by an Israeli soldier, my occupier, and asked to show my ID. If I want to enter East Jerusalem, where I was born and went to school, I have to present my ID, and a special permit from the Military Administration (called the Civil Administration) allowing me to enter occupied East Jerusalem during specific hours of the day, if that is my destination, without being allowed, under any condition, to spend the night in the city, even if I wanted to visit my daughter Jumana’s house and play with my granddaughters Dana, Dahlia and Lena, or at my brother Khalil’s home in Beit Hanina, an Arab Palestinian neighborhood of East Jerusalem where they live. It just so happens that they have Jerusalem resident cards and not a Palestinian ID card, as I do.

Memories of Administrative Detention in an Israeli Jail

The first time I ever felt that I didn’t need to carry my ID was on my first day in an Israeli military jail called Junied near Nablus in May 1990, when I was arrested and detained under Administrative Detention for six months by a military order for “being dangerous to security and public order,” without any charge or trial. At that time, I had to give my ID, money, belt and all other belongings which were in my pockets to the guards. And the next morning, when I was allowed with the other prisoners to go outside for one hour walk, called “picnic” (Tiyoul in Hebrew), in the small courtyard of the jail section, unconsciously I reached into my pocket before leaving my cell to make sure that I had my ID, and then remembered that they had taken it. That gave me a special feeling of freedom, because I discovered that in jail I’m not obliged to carry any identification document. Actually, in the jail there is nothing more to fear. I said to myself, the maximum freedom you can ever have is when things can’t get worse and you have nothing to lose.

Administrative Detention for periods of three to six months, which can be renewed for unlimited times that may extend for several years, expulsion, house demolition, and many other harsh measures, are practiced by Israel against Palestinians according to the British Emergency Regulations, which were applied by the British Mandate in Palestine before 1948. These regulations were later described by former Israeli Minister Shmuel Tamir, who himself was arrested by the British Mandate police under these regulations, as typical Nazi laws; when he became a Minister of Justice in Menachem Begin’s first Likud government in 1977, he abolished them inside Israel but kept them in the Occupied Palestinian Territories.

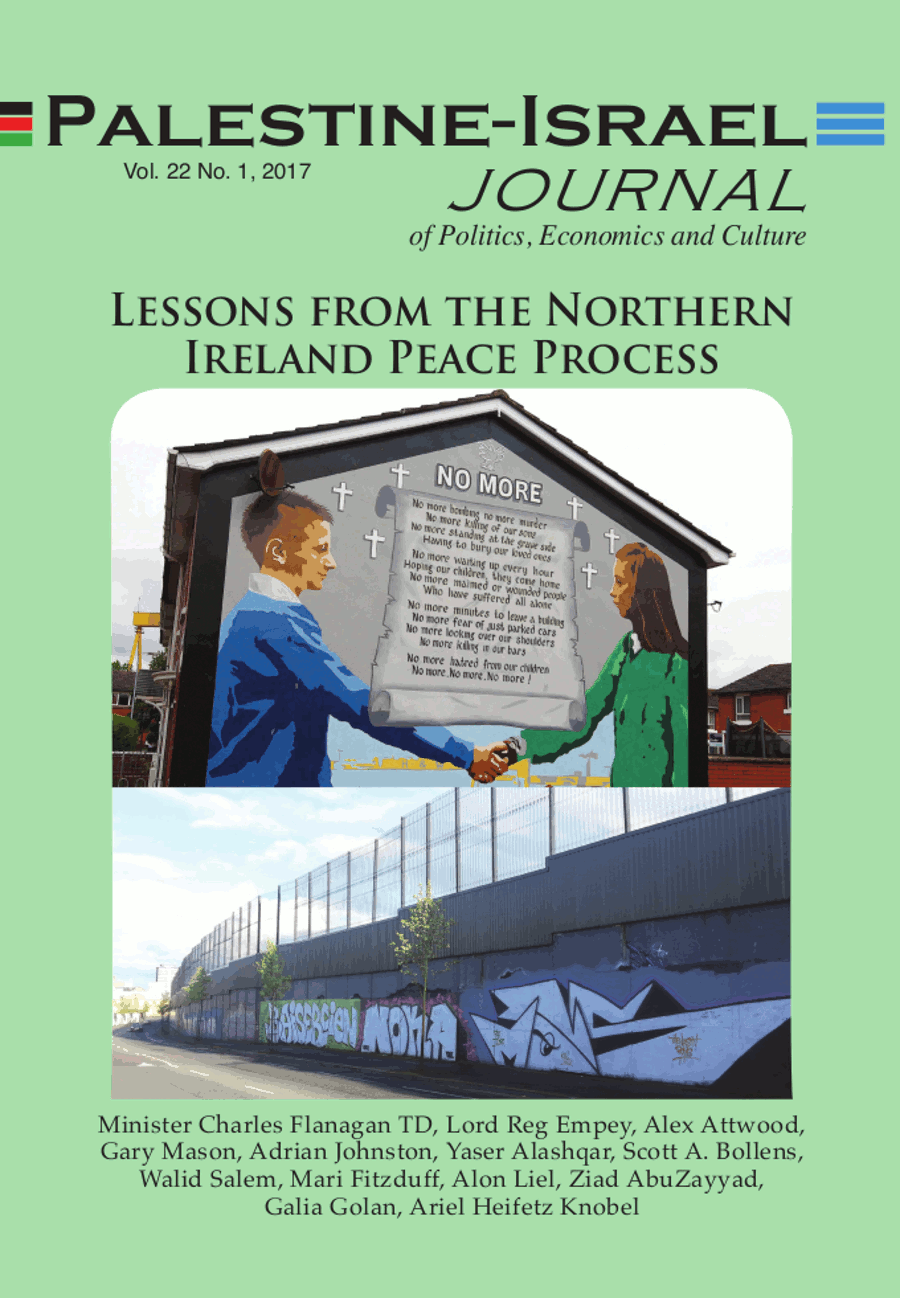

Our stay in Belfast was very pleasant but intensive, too. All day we were rushing from one office to the other and from one meeting to another. We were learning a lot and establishing relations with different institutions, organizations and individuals and preparing together material for our issue devoted to lessons to be learned from the Northern Ireland peace process.

Crossing the Border without Restrictions

I learned from the people I met that crossing the border between the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland was not as easy in the past as when we crossed it this time. We realized that before the peace process, it was under tight security measures, many attacks were carried out there and victims fell. It is only after the peace process started that movement was allowed to flow smoothly without any restrictions in a way that anyone crossing the border doesn’t feel that she/he is crossing from one country to another. If I were an Irish Republican, I would say that the peace process, from this aspect, unified Northern Ireland with its Republican mother even if not de jure. This can be counted as a positive outcome of the peace process, even though the process is still fragile and has yet to achieve a final result.

Taking this conclusion back home, I see things differently but see no reason why we should not emulate this example, even if the situation between Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territories is totally different and possibly much worse than it was on the border between the Republic and the North before the Northern Ireland peace process.

After the failure of the 2000 negotiations in Camp David and Taba in Egypt afterwards, and the eruption of the second intifada, Israel imposed tight closures on the Occupied Palestinian Territories and started building the Separation Wall, which is almost finished. Palestinians are not allowed to visit East Jerusalem which is an integral part of the OPT without a special permit which is not easy to get. Furthermore, there are check points and restrictions on movement inside the OPT.

Life for the Palestinians is very difficult, while at the same time there is no political horizon for a political solution that can improve or change the conditions of their lives. Israel can learn from the Irish experience and lift restrictions on the Palestinians between the different parts of the OPT and between them and Jerusalem or Israel. Easing the pressure on the Palestinians and allowing them to move freely to Israel and East Jerusalem would help them to have jobs or work and improve their economic situation. Palestinian workers could work in Israel and go back to sleep in their homes in Palestine, without being involved in social problems within the Israeli society, while the money they earn would eventually find its way back to the Israeli economy — something that Israel will benefit from.

Allowing Palestinian workers to work in Israel would contribute positively to more stability and calm. In the long run we have to live together, and being more tolerant and giving the Palestinians something that they will not want to lose is very important. This would help to make life easier in the absence of a final peace agreement and would create a more suitable atmosphere for resuming efforts of making peace and conciliation. Security fears always exist but should not be misused to justify a political agenda or tie our hands, preventing us from trying a different approach.

A Red Light That We Should Not Wait 200 Years to Learn

For many years, I used to read and hear in the media that the Irish conflict was a domestic conflict between Catholics and Protestants. And I admit that it was confusing: Why are Christians fighting Christians? But when I became interested in that issue in the 1990s, when the efforts to achieve peace in Ireland were accelerated, I realized that it was not a religious conflict but a national one. I realized that Protestants wanted to continue to be part of Britain and Catholics wanted to get rid of British rule and unite with the Republic of Ireland, which they are an integral part of. Then I found out that the Protestants were brought by Britain to settle in Northern Ireland more than two centuries ago to change the demographic balance of that province in favor of Britain, the Protestant country, while the Catholics were the people of that province before the British came to take over Ireland.

For me this historical fact switched on a red light. Israel is doing in the OPT what Britain did in Northern Ireland, so why should we wait another two hundred years to find ourselves where they were or are? The Israeli settlements project will make the Palestinian-Israeli conflict unsolvable. The Palestinian people will not vanish. On the contrary, they have a high birthrate, and all estimates predict that their number in Mandatory Palestine between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea will more or less equal that of the Israeli Jewish citizens within 10 to 15 years and will outnumber them in few decades.

A Political Problem That Requires a Political Solution

If Israel wants to keep its Jewish identity it has to withdraw from the Occupied Palestinian Territories and allow the creation of a Palestinian state through a fair and just peace process. Otherwise, it will turn into an apartheid regime unless it annexes the OPT and gives the Palestinians full equal citizenship rights, something that it will not do because Israelis insist on having a Jewish state and are against a bi-national state. Israel has to choose between being Jewish or democratic.

So the lesson to be learned is that Israel should immediately respond to the international demand, expressed lately in the United Nations Security Council Resolution 2334 and halt all settlement activities to preserve the option of the two-state solution, and engage in a fruitful peace process such as Britain and Ireland did.

The Palestinian-Israeli conflict is a conflict between two peoples who claim the same right on the same piece of land: Palestine. Palestinians believe that Palestine is their national homeland where they have lived for thousands of years and see the Israelis as invaders who were granted land that doesn’t belong to them by a country that has no right to grant this land to the Jews, meaning the Balfour Declaration in 1917 by Britain. And the implementation of this declaration was enhanced by the Europeans after World War II to compensate the Jews for their sufferings at the hands of the Nazi regime, which the Palestinians were not part of and for whose crimes they are not responsible.

Israelis claim that this land belongs to them by a God-given promise and obtained control over this land by force and international politics. God is not a land registrar, but real politics show that we have a reality on the ground which is the state of Israel controlling all the area of geographic historical Palestine including the Israel of 1948 borders and the Palestinian territories occupied in 1967. Neither side can make the other side disappear. This is a political problem which needs a political solution. Seventy years since the creation of Israel in 1948 and 50 years since the occupation of East Jerusalem, the West Bank and Gaza Strip as a result of the 1967 war has not guaranteed stable and quiet control of Israel over this land. And if military power, oppression and suppression of the Palestinian people have not resolved the problem throughout this time, then another method should be tried.

Israel Needs Its Own Tony Blair

We were told by some of our hosts in Ireland that former British Prime Minister Tony Blair came to the conclusion regarding the Northern Ireland conflict that this was not a military conflict but a political one, and the solution should be a political solution and not a military one, and he chose the political path. Blair had a large majority in the British Parliament and could go ahead on the path to a political solution without difficulties.

As a matter of fact, it was not only Tony Blair. It was the British government since the early 1990s, long before Blair came to power, and the Irish government, along with the European Union and active pressure and support from the United States, which pushed for a political solution to the Irish issue for a range of political and economic interests. Political negotiations had been already underway by 1996, before Blair became prime minister. Blair responded to, and supported, this developing situation and the changing geopolitical conditions.

Israel, in my view, needs an Israeli prime minister who will come to this same conclusion, that this is a political conflict that needs a political solution. It needs a leadership which has both a strong willingness and support from the political establishment to advance negotiated solutions. This is what Blair had. This is another lesson that needs to be learned.

The Crucial Role of Former Prisoners in Ireland and Palestine

During our study tour in Belfast, we met with a number of former prisoners. Some of them are members of Northern Ireland Parliament, and others are active in civil society organizations. As in our case, prisoners are a major source of legitimacy for a process or an agreement, which some will claim is making concessions on national rights. Prisoners played a role in the success of the Northern Ireland peace process by supporting it. One of the major issues which have been integrated into the foundations of the Good Friday Agreement is the release of prisoners in order to encourage their political leaders to engage in negotiations and the peace process.

Of course, as we were told, there are a very small number on both sides, Republicans and Loyalists, who refused to support the peace process but the majority supported it and contributed to its success. Some of those not supportive of the peace process are in prison for offences committed post-1998, and some of their associates also outside and active in "dissident" activities. Here it will be almost the same. A reasonable peace process will be supported by the majority of the Palestinian prisoners and help the political leadership in selling any agreement to its people. And as a matter of fact, a large number of Palestinian activists or even leaders such as Jibril Rajoub, Mohammed Dahlan, Hisham Abdul Razik, Sufyan Abu Zaidah, Qadura Faris and others who support the two-state solution and participate in peace dialogues with Israelis are former political prisoners in Israel.

The Israeli government should not continue its character assassination of Palestinian prisoners by labeling them terrorists or criminals with blood on their hands, as Israeli leaders always say. A way back should be left open because these same prisoners will serve as a vehicle to bring peace to the people. It is not in the interest of either side to burn all bridges and close the door to a possible positive role for the prisoners in making peace. And prisoners, as political activists and members of civil society organizations, can play an important role in building peace through building bridges between the two communities.

My Allies in Confronting the Occupation

On the general public level, there are Palestinians who oppose any joint activity between Israelis and Palestinians, claiming that these activities are normalizing the relations with the occupation. They argue that those who are involved in joint activities with Israelis in dialogue promotion are are collaborators with the occupation. On the other side, Israelis who are against the occupation and still believe in peace and support the two-state solution are labeled in Israel as leftists, traitors or self-hating Jews. Such Israelis are my allies in confronting the occupation and bringing the two parties together to end the occupation.

A similarity also exists between the Irish method and the Palestinian- Israeli method in this regard. In Northern Ireland we visited a civil society organization which is running a project that is encouraging Catholics and Protestants to live in the same apartment building as good neighbors. One activist told us that her car was set on fire, and she was forced to leave her apartment by those in her neighborhood who did not like her organization’s work in bringing the two rival communities to live side by side, because they consider her and her colleagues as collaborators. It’s the same here on both sides of the fence, but it will not deter Israeli and Palestinian peace activists from continuing to build bridges and sow the seeds of conciliation between the two peoples, having in mind that the only practical solution is ending the occupation and creating an independent sovereign Palestinian state side by side with the state of Israel along the 1967 lines with Jerusalem as a shared city of two capitals for the two states.

Palestinian Independence Is Still Far from Reality

Though the Palestinians have, since the Oslo Accords in 1994, established separate governmental institutions serving as the Palestinian Authority (PA), they still lack freedom in functioning. All the computerized systems of population registration, vehicle registration and licensing are connected to the Israeli system and under full Israel control. Israelis control all outlets, import and export, water and electricity and all our life aspects. Without ending the Israeli occupation, Palestinian independence is far from reality and the PA has no real share in running the affairs of its own people beyond being a sub-agent to the occupation doing the dirty job of civil services funded by donor countries freeing Israel as the occupier from its obligations towards the residents of the occupied territories according to Geneva Fourth Convention of 1947.

From the Northern Ireland peace process, we learned that Catholics in Northern Ireland were not part of the police or the government before the peace agreement, and now they have their own share in the police, the parliament and government agencies. The Good Friday Agreement also introduced equality measures and citizenship rights for Catholic and Protestant communities in Northern Ireland to support, among other things, equal representations and opportunity in the employment and institutional sector.

Israelis have to understand that creating an atmosphere of peacemaking requires opening the door for Palestinians to share in all decisions related to their daily life and future, including population registration, water and electricity, and vehicle licensing. If the Palestinians were to have a real share in running their own affairs, this would help to build the sense of equality and partnership in building a future of peace and co-existence.

No One Wants to Return to the Situation before the Good Friday Agreement

To conclude, I can say that I learned a lot from our study tour in Dublin and Belfast, though some of the things I learned still require more thinking and absorbing. But one thing I should add as a substantial conclusion rises above all that I learned. From almost all my meetings and from all the people whom I met from both sides, I received the same answer to the same question which I was asking everybody.

The question was: Would you like to go back to the situation that existed before the ceasefire and the Good Friday Agreement? And the answer was: Absolutely not. This had an overwhelming impact on me but definitely was well understood. People want peace, quietness, prosperity and a good life as well as their national rights, equality and justice. This is what politicians should think about and not their own political careers or their party’s political interests. This is the final lesson, which should be the final act in the Middle East peace symphony.