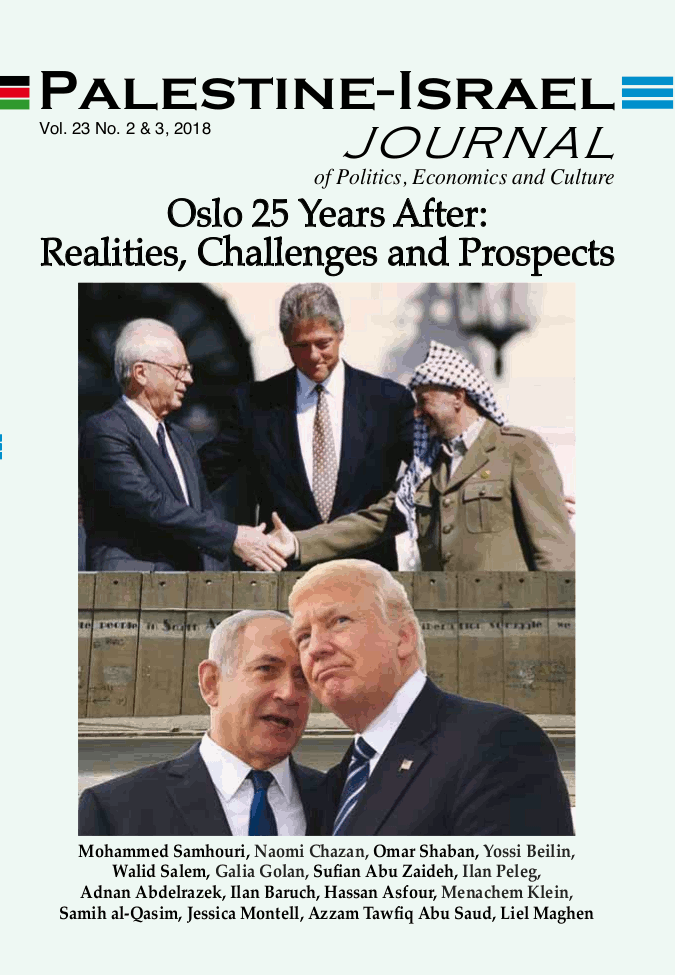

Many people felt that they were witnessing history in the making, the end of the 100-year bloody conflict between the Jews and the Palestinians, when they saw Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat on the White House lawn on September 13, 1993, with a beaming U.S. President Bill Clinton looking on as they signed the Oslo Accords.

This was soon followed by the awarding of the 1994 Nobel Peace Prize to Rabin, Arafat and Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres. “Euphoria” was the word used by many. “We were jumping in the streets; I never saw anything like it,” said Palestinian Ambassador Hind Khoury at the roundtable discussion that appears in this issue. Many believed that the road to Israeli-Palestinian peace was now irreversible and that nothing could stop the forward momentum.

However, the Oslo Accords, officially known as Oslo Declaration of Principles (DOP), were not a peace agreement. They were an agreement to launch a process that was supposed to be completed within five years, without defining the outcome of that process. The expectations of each side were different and possibly contradictory.

Though the words “Palestinian state” were not mentioned in the agreement, and a clear end goal was not defined, the Palestinian negotiators were saying openly that their final objective was the establishment of a Palestinian state, but the Israeli leadership did not share that goal.

Then-Israeli Deputy Foreign Minister Yossi Beilin, one of the primary architects of the Accords, says in our interview with him in this issue that “I was very, very happy that it was signed, and very worried about the future. My big fear was that extremists on both sides would use the five years to torpedo the implementation.” And those fears were realized.

On February 25, 1994, right-wing settler Baruch Goldstein killed 29 Palestinians praying in the Ibrahimi Mosque (Cave of the Patriarchs) in Hebron. A few others later died of their wounds. The Hebron massacre was followed by Palestinian suicide bombings against Israeli civilians, and in November 1995, Israeli right-wing extremist Yigal Amir, inspired and encouraged by extremist rabbis, assassinated Rabin. This strange alliance between the enemies of the agreement on both sides — who shared the same goal but for contradictory reasons — succeeded in bringing the Oslo process to a halt.

Attempts to restart the process by Prime Minister Ehud Barak and President Arafat at Camp David in 2000 and by Prime Minister Ehud Olmert and President Mahmoud Abbas in 2007-08 failed, as did U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry’s attempts to facilitate an agreement in 2013-14.

Barak has been accused of pushing for the convening of Camp David Summit without enough preparation, and after it failed he undermined the Israeli peace camp by blaming the Palestinians for the failure, declaring that “we have no Palestinian partner for peace,” a slogan which was immediately adopted by the right wing in Israel, despite the fact that the PLO leadership has consistently declared its support for a two-state solution based upon a Palestinian state in the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem alongside Israel on the June 4, 1967 lines, living in peace and harmony with the State of Israel.

Israel Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, under pressure from U.S. President Barack Obama, paid lip service to the two-state solution in his Bar-Ilan speech in 2009, but he clearly has not done anything to promote it and is now saying only that he would be willing to grant the Palestinians a “state-minus.” Furthermore, his Likud party declared in 2017 that it opposes the establishment of a Palestinian state.

While the negotiations to implement the Oslo Accords were under way, successive Israeli governments were talking peace while intensifying settlement activities on the ground that undermined the possibility of withdrawal and the establishment of a Palestinian state. When the Oslo agreement was signed, there were approximately 110,000 Israeli settlers living in the West Bank, with an additional 146,000 settlers living in the new Israeli neighborhoods in East Jerusalem. Today the number of settlers in the West Bank, including East Jerusalem beyond the June 4, 1967 Green Line, total some 600,000-750,000, according to 2017 statistics. The approximately 8,000 settlers who were living in the Gaza Strip were evacuated during the 2005 Israeli disengagement from Gaza.

In addition to settlements activities, the recent Nation-State Law passed by the extreme right-wing government declares that “the Land of Israel is the historical homeland of the Jewish people, in which the State of Israel was established” and “the right to exercise national self-determination in the State of Israel is exclusive to the Jewish people.” It also downgraded Arabic from an official language to one with a “special status,” and declared that “Jerusalem, complete and united, is the capital of Israel” and that “the development of Jewish settlements project is a national value.”

This is in violation and contravention of United Nations Security Council Resolution 181 — the Partition Plan that serves as the basis for Israel’s international legitimacy — which calls for the establishment of two states, one Jewish and one Arab, in the area of Mandatory Palestine. The law also obstructs any attempt to find a political solution to the conflict based upon ending the Israeli occupation and creating a Palestinian state living side-by-side with the State of Israel in peace and harmony.

Many believe that this is a watershed moment in the history of the conflict, given that the final borders of the State of Israel have not yet been defined.

The new law runs counter to the principles in Israel’s Declaration of Independence, which states that the State of Israel will “foster the development of the country for the benefit of all its inhabitants; it will be based on freedom, justice and peace as envisaged by the prophets of Israel; it will ensure complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants irrespective of religion, race or sex; it will guarantee freedom of religion, conscience, language, education and culture; it will safeguard the Holy Places of all religions; and it will be faithful to the principles of the Charter of the United Nations.”

The Nation-State Law has already sparked a public struggle being waged by minority groups in Israel, with the support of Israeli liberals, over the future of Israeli society; the rights of the Palestinian citizens of Israel, who make up approximately 20% of the population; and relations between the two peoples living in the area that was Mandatory Palestine between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. The slogan of the struggle is “equality for all.”

While, in theory, the establishment of a Palestinian state is still possible, based on a minimal mutually agreed upon land swap that would enable 80% of the settlers to remain within the new, sovereign borders of the State of Israel, the reality on the ground shows that the window of opportunity for a two-state solution is rapidly closing. Israel will have to choose between an end to the occupation and the establishment of a Palestinian state alongside the State of Israel; an apartheid Greater Israel built on bloodshed and suffering and which denies equal rights to the Palestinians and other minorities; or a one-state solution with equality for all. The Palestinians will also have to develop new strategies to confront the situation and overcome their divisions in order to confront the danger of the growing power of the right-wing atmosphere that is sweeping Israeli society and killing any chance of a peace agreement.

With this issue, we have created a major resource for everyone — Israelis, Palestinians and internationals — who wants to understand the impact, the successes and the failures of the Oslo process and the possibilities for the future. The common theme that emerges from the broad range of authors is the clear need to develop new strategies to revive the quest for a resolution of the conflict, for the sake of both the Israeli and the Palestinian peoples.