The following is an edited transcript of an interview with Co-Editors Hillel Schenker and Ziad AbuZayyad conducted by Phillip Fischer on February 12, 2020 at the PIJ offices. Ziad AbuZayyad is one of the co-founders of the Palestine-Israel Journal. Previously he worked as an attorney and journalist, and served as a minister in the Palestinian Authority. Hillel Schenker is a journalist and peace activist; he was an editor for the Israeli peace monthly New Outlook and was involved in the founding of the Peace Now movement. Phillip Fischer is an intern at the Palestine-Israel Journal, whose MA thesis will be devoted to the influence of local and international NGOs on the peacebuilding and reconciliation process in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

In early 1994, in the midst of the Oslo peace process, Palestinian journalist Ziad AbuZayyad and Israeli journalist Victor Cygelman decided to launch the bi-national Palestine-Israel Journal. Hillel Schenker, a journalist and veteran peace activist, has served as the Israeli co-editor since 2005. Despite the ongoing challenges the peace process faces, especially in light of the Trump administration’s so-called peace plan, the Palestine-Israel Journal remains faithful to its roots and diligently continues its the quest for a political settlement between Israel and Palestine based on the two-state solution: Israel and Palestine living in peace and harmony along the June 4, 1967 lines, with Jerusalem shared as the two capitals of the two states. Motivated by the principle of advancing nonviolent, peaceful solutions and advocating for a better understanding of each other, the Journal continues to include in its issues a great variety of political views from Palestinian, Israeli and international contributors. Throughout its prolific history, the Journal has served as a channel for debate and a public platform for different academics, decision-makers, activists and journalists who seek a just solution to the conflict.

Philipp Fischer: The first issue of the Palestine-Israel Journal was published 25 years ago. Which events led to the foundation of the Journal?

Ziad AbuZayyad: I was publishing a Hebrew-language Palestinian newspaper called Gesher (Bridge). When the Oslo Accords were signed, I stopped publishing the paper. At the same time, Victor Cygelman, a friend of mine who was involved in New Outlook magazine, an Israeli peace monthly based in Tel Aviv, also stopped publishing. So, we started talking about having a joint publication which could support the Oslo Accords and encourage people to start talking about sensitive issues related to the peace process. We also wanted to provide decision-makers and negotiators with material about each side.

After agreeing on the goal and mission of such a publication, we started working with a small number of Israelis and Palestinians to advance the idea. We tried to register the Journal at the Israeli Ministry of Interior as a nonprofit organization, but they refused to register us because of the word “Palestine” in our name, so we went to the High Court. Eventually, our lawyers found a compromise and registered us as Middle East Publications, telling us that we can use any name we want without officially registering it at the ministry. So, officially we are a nonprofit organization called Middle East Publications, but in practice we are the Palestine-Israel Journal.

Our idea was to have an equal partnership between Israelis and Palestinians. We had two editors — one Israeli and one Palestinian; two managing editors — one Israeli and one Palestinian; and an equal number of staff from both sides. But more important is the Editorial Board and also the material in the Journal. We do our best to have an equal number of Israelis and Palestinians on the Editorial Board, and we try our best to have half the material in the Journal written by Israelis and half written by Palestinians. On occasion there are more articles by Palestinians or by Israelis, but we don’t make a big fuss about it as long as we are covering the subject from the point of view of the two sides.

Fischer: After Victor Cygelman left, Hillel Schenker took over his position?

AbuZayyad: Victor Cygelman wanted to retire at the end of 2001, so he was replaced by Danny Bar-Tal, a professor from Tel Aviv University. Danny was here for a few years until he left for a sabbatical in the United States. He chose Hillel to succeed him, and since then I have been working together with Hillel.

Hillel Schenker: I first came to the Journal in 2002, but I replaced Danny Bar-Tal in 2004-05. I have felt for many years that it is very important that Israelis and Palestinians work together to end the conflict. We will always be neighbors, we will always work with each other, and it’s in both the Israelis’ and Palestinians’ interests. Palestinians, of course, want to end the occupation and achieve national rights, national self-determination, and I always felt this was [in the] Israeli interest as well. It’s very important to end the occupation for both the Israeli and Palestinian interests.

AbuZayyad: Hillel was not new to this field. He was involved in New Outlook, and we had known each other for a long time. So, when he came here, he wasn’t new to us, and we weren’t new to him. He believes in the same cause that we believe in and work for, so he just came home. We both feel that we belong to the same school, the same idea and the same struggle for peace and justice to end the occupation.

Schenker: Exactly! I think we had met already in the 1970s. In other words, we knew each other beforehand, but then I came to the conclusion that it is vitally important that we work together.

What happened, essentially, was that I was studying at Tel Aviv University, considering an academic career, and then two things happened. The first thing was the Yom Kippur War, and I ended up spending seven months on the Golan Heights as a soldier. That convinced me that I had to change my priorities and devote all of my energy to achieving peace and preventing another war. Then in 1977, [Egyptian] President [Anwar] Sadat came, and peace no longer was just theoretical; it became a very concrete thing. That’s when I began working at New Outlook. The step after the Egypt-Israeli peace was to get to the core of Israeli-Palestinian conflict and resolve it.

Fischer: How did the atmosphere change over the years from the founding till today?AbuZayyad: We started against the background of the Oslo Accords. We were enthusiastic about making peace, and we wanted to contribute something to the process. Well, now we, like many other people, are disappointed and frustrated. We feel that all our hopes were not realized, and we lost faith in the process. But we still hope that one day things will change for the better in the direction we want. At the moment, however, we are very disappointed in the failure of the Oslo Accords and the continued occupation and settlement activities in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT), which are killing any possibility of reconciliation and undermining the idea of the two-state solution.

Schenker: The first major turning point was when the 2000 Camp David summit failed to produce results, although the Oslo Accords said that a permanent agreement would be reached after five years. The 2000 Camp David summit, hosted by [U.S.] President [Bill] Clinton with [Israeli Prime Minister Ehud] Barak and [Palestine Liberation Organization President Yasser] Arafat, was the attempt to do that but, unfortunately, it did not produce a solution. Then came the second intifada which, unlike the first intifada, was very violent, and that essentially marked the end of the Oslo process. It became much more difficult, but the goal remained the same. We knew that we have to resolve the conflict based on a two-state solution, if possible. Despite the difficult conditions of the second intifada, the Journal continued its joint work.

Fischer: Did the failure of the Oslo Accords affect your work?

AbuZayyad: Of course we were affected: first, becoming frustrated and disappointed, and second, regarding the journal itself, we realized that we have to continue our work but expand the area of our attention beyond only supporting the negotiations to dealing with more general topics of concern to the future of the two peoples.

Furthermore, concerning our joint dialogue activities, we were confronted with new regulations preventing Israelis from going to the Palestinian side and Palestinians from coming to the Israeli side. As a result, if we want to invite Palestinians to participate in joint activities on the Israeli side, we have to obtain permits from the Israeli security authorities, which means, practically, that the Israeli security decides with whom we can or cannot work. This is a problem for the freedom, neutrality and objectivity of our work.

Later, people-to-people programs were halted, and we are facing financial difficulties as a result of lack of funding from international sources. The Journal is facing financial difficulties which are threatening our ability to continue to function.

Fischer: So, there was less funding for your approach?

Schenker: There are two factors. One factor is that there are many other competing issues, such as the problem of the refugees from the Middle East going to Europe and the Syrian civil war creating many more refugees. A lot of the international community’s attention went to those needs. Also, the failure to be able to resolve the conflict has led to frustration on the part of the international community and donors in terms of investing and trying to resolve the conflict.

One of the ideas, for example, is the creation of an international fund for Israel/Palestine. We did a special issue on the Northern Ireland peace process, where the international community created a huge international fund to help support Irish civil society in building a constituency for peace on all sides to the conflict. Unfortunately, the international community has not done the same thing yet for the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. We really need that, but that’s the big challenge. The international community, we believe, is affected by the conflict and should increase its efforts to support those on the ground who are working to resolve it. Right now, that's why we face serious financial challenges.

Fischer: The Palestine-Israel Journal is a joint project of Palestinians and Israelis. How did this cooperation develop over the years, and what challenges did you face?

AbuZayyad: At the beginning, we worked very well and didn’t have any problems, but later, as a result of the deterioration of the political situation in Israeli-Palestinian relations, all joint projects became difficult. This is true especially for the Palestinians, because some Palestinians think that any kind of joint activity is a kind of normalization of the occupation. So, we faced difficulties. My advantage on the Palestinian side is my background. I was one of the active national leaders in the OPT before the creation of the Palestinian Authority (PA) and before the Oslo process. I’ve been arrested by the Israeli authorities several times, and I was an elected member of the Palestinian Legislative Council (the PA parliament). So, I have my own legitimacy and credibility in my own society. Therefore, it is not easy for people who are against normalization to discredit me. My presence here gives some protection to the Journal and to the joint work. We are an integral part of the struggle against the occupation for the sake of a just, durable peace.

Schenker: On the Israeli side, there has been an attempt by the right wing, which has been growing all the time, to delegitimize any joint work with Palestinians as being disloyal to Israeli interests and working with the enemy, etc. There is another factor: fear. Many people in Tel Aviv, where I live, ask: “Aren’t you afraid to go regularly to East Jerusalem? “Because that’s their image, that it is a dangerous place. But it is absolutely essential to continue working together with the hope that Jerusalem will be a shared city, a capital for both — West Jerusalem a capital for Israel, East Jerusalem a capital for a future Palestinian state. So, on the one hand, people ask, “Aren’t you afraid,” but on the other hand, many people will say — Tel Aviv, after all, is a very liberal city — that they are very proud of the fact that I am continuing to do this, that I am representing them. They see the continued existence of a joint journal to be a source of hope and light in a very pessimistic situation.

Fischer: What would you describe as the biggest achievement of the past 25 years?

AbuZayyad: Well, first of all, the biggest achievement is that we are still publishing (laughs). Many others would have become desperate and stopped doing what they believed in a long time ago. So, the biggest achievement, in my opinion, is that we are still fighting, we are still struggling, and we are still publishing this journal. On the other hand, despite all the difficulties, there are people — especially the young generation worldwide — who read the Journal, are influenced by it, and who make use of it. We see this as an achievement.

Schenker: I would say that there are two particular sectors where we have a really strong impact. One is the area of students and lecturers who are dealing with political science, international relations, Middle Eastern studies and other related areas. We have been a very major resource in their work, and that’s why so many of the international interns come to us — because they have found us in the course of their studies. Students, after all, are the future of civil society activism, academia and sometimes also political leadership. The second thing you can see whenever we have a public launch of one of our issues is that there is a tremendous interest on the part of the diplomatic community based here in Israel and Palestine, who are always very eager to come. They receive the issues with great appreciation, and they come to the events because it really helps them in terms of their formulation of policy advice for their various foreign ministries.

Fischer: Now that things have changed so much over the last 25 years, and now that this already infamous “peace plan” has been published, what do you hope for the future? Do you have any hope that things will change, or will they deteriorate?

AbuZayyad: We are going through a very delicate and dangerous stage of the conflict. Things can’t be achieved without the involvement of the United States, because it is the leading figure of the world and has its special relationship with Israel and is influenced by Israel. Now, however, we see that the United States is becoming part of Israel, not that Israel is becoming part of the United States. We see that there is an administration in Washington which is to the right of the current right-wing Israeli government. We see an American ambassador in Israel who is like a fanatic settler, and he is proud of being a supporter of the Beit El settlement. He speaks exactly like any right-wing fanatic settler in the OPT. So, with this administration, I don’t see any chance for any solution sponsored by the United States.

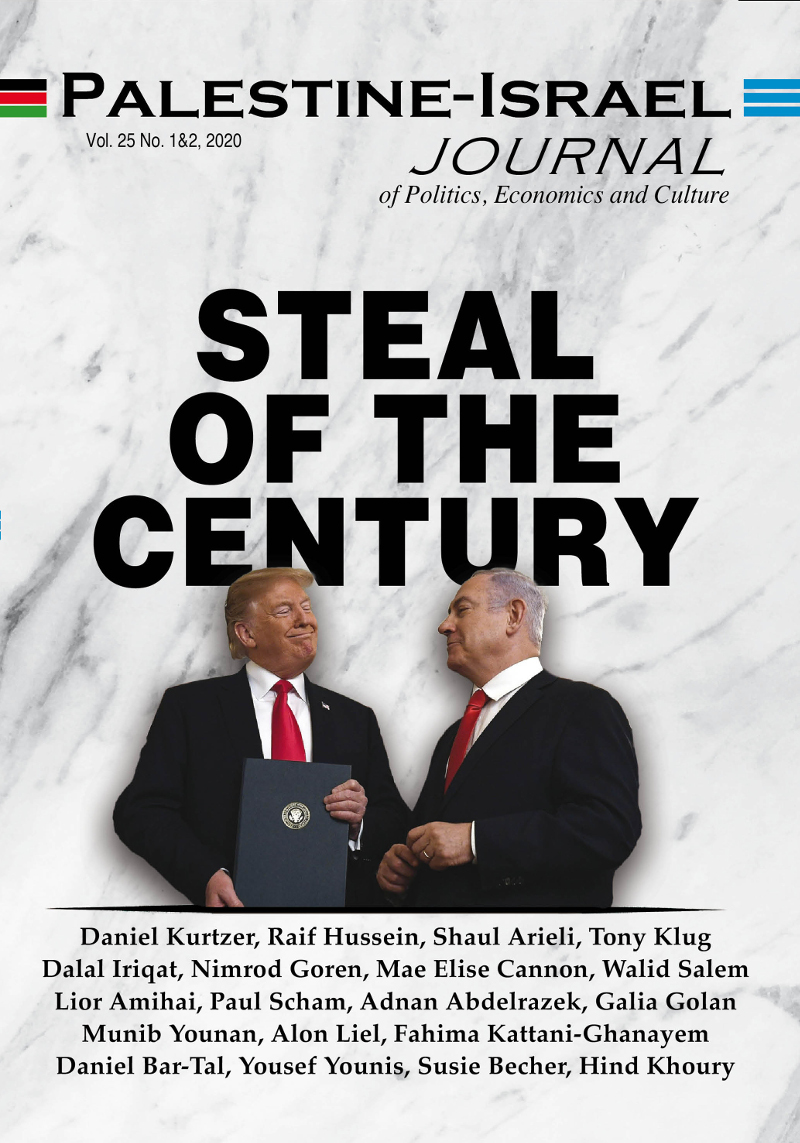

On the contrary, what Trump announced lately and described as a vision for peace or the “ultimate deal” or the “Deal of the Century” only had a very negative impact on the situation. That is because, on the one hand, it is encouraging the Israeli right to continue the plans for annexation and it legitimizes the Israeli occupation and annexation and discredits the United Nations resolutions and international legitimacy. At the same time, it may push the Palestinians to become more violent. Since 1988, the Palestinians have adhered to the principle of the two-state solution, and to this day the Palestinians are trying to remain committed to the talks and agreements with Israel and keep the security coordination between the Palestinian and the Israeli security forces to prevent violent, bloody attacks against Israelis and against Jews. But I think what Trump is doing is endangering the Israelis, because he is pushing some Palestinians to go back to violence and terror against the Jews and to pressure their government to stop security coordination with Israel.

Schenker: First of all, the alternative of a one-state solution is not realistic in any foreseeable future, given the ongoing conflict and the wars in 1948, 1967, 1973, 1982 and the Israeli-Gaza wars. There is so much suspicion and lack of trust between the two sides that any idea of having a one-state solution in any foreseeable future is simply unrealistic. That’s why the two-state solution remains the only viable solution, even if it is becoming more difficult to achieve. There is no question that the Trump plan was formulated with only one of the two partners to what is supposed to be the solution. It’s absurd to have a plan that did not have any input from the other partner, the Palestinians.

Looking toward the future, I am hopeful that in November 2020 there will be a new president of the United States, because all of the Democratic candidates, from the moderates to the more progressive ones, have been highly critical of this “Deal of the Century.” They have all said that they would want to re-establish ties with the Palestinians and move toward serious negotiations between the Israelis and Palestinians. Now, we all know, as Ziad said, that you can’t really expect any solution without American involvement, but it has to be constructive American involvement.

The international community has always played a role, starting with the Balfour Declaration and the British Mandate, the UN Partition Plan, Resolutions 242 and 338, and most recently, in December 2016, Resolution 2334, which stated clearly that the settlements are illegal according to international law and that you must have a two-state solution. So, we are looking to the international community, also to Europe, and to a degree to the Arab League, for support. After all, the Arab Peace Initiative of 2002 is essentially a formula where the entire Arab world, backed by the entire Islamic world, would be ready to recognize Israel and have normal relations with it on condition that a Palestinian state is established in the West Bank and Gaza, with East Jerusalem as its capital. So, we have formulas to achieve a solution; we have the Geneva Initiative. What we need is greater international involvement, and we also need — we, as Israelis and Palestinians — to develop effective strategies to face current realities. That is one of the roles that we at the Journal are playing: analyzing and making proposals for strategies that should be adopted by Israelis, Palestinians and the international community.

Fischer: There is a great variety of views and opinions in the Journal. Why is it so important to cover every opinion from left to right, and which opinions are not represented in the issue?

AbuZayyad: From the very beginning, we decided that there should be no censorship. We are totally against censorship. But we agreed that the platform of the Journal would be: support for the two-state solution, for peace between the two peoples and for the right of self-determination. So, our platform is that we are for a two-state solution, for a Palestinian state alongside the Israeli state. We don’t publish any article that denies the right of the Israelis or the Palestinians to exist, and we don't publish any article by a Jewish settler in the OPT because we view the settlements and the settlers as part of the infrastructure of the Israeli military occupation.

Schenker: As far as the diversity of views, of course, most of the authors are people who essentially support the position of the editors and the Editorial Board. We also welcome well-written and serious articles from people on the Israeli right whose opinions we would like to know. We have published articles by members of the Likud party and by other right-wingers in order to be able to understand their reasoning and to be able to confront them. The same goes for the Palestinian side. If there is somebody close to Hamas who wants to present Hamas’s views, we welcome that in order to be able to understand and to confront. Of course, this is on condition that the author doesn’t deny the other’s right to exist.

Fischer: After all the disappointment due to the failure of the Oslo Accords, what keeps you going to do this work as a joint journal working for peace and reconciliation?

AbuZayyad: Well, it’s a challenge for us. We believe in the idea, and we don’t want to throw our hands up in the air and say that we failed and that the idea failed (laughs). We are still trying to do what we believe in, despite all the difficulties and despite the lack of funding for the Journal.

Schenker: I would add that if you look at our archives, you will see that we have had hundreds, maybe even close to a thousand, authors who have contributed articles, and we don’t have the funds to pay them. Serious people, influential people, voluntarily contribute articles because they feel it is important and also influential. We have never had a problem finding enough articles to fill each 128-page regular issue. On the contrary, sometimes we don’t have room for all of the articles. People are continually ready to send articles, because they feel it is important to write for the Journal.

Fischer: What are your hopes for the future?

AbuZayyad: We hope that we get funding and continue publishing (laughs).

Schenker: That’s basically it. I also hope that the international community will become more involved in helping to resolve the conflict.

AbuZayyad: Our ultimate goal would be that we see a solution to the conflict. Our hope is not only to continue publishing — on the contrary. We want to see that our goal is accomplished, that there is peace, and then there would be no need for us and we would have to think and write about other topics related to a fruitful future post-conflict and post-occupation.

Schenker: We would like to be living in a post-conflict reality.